Twenty-five years ago, I made a conscious choice to avoid the issue of race. And because I am a white woman, living in a majority white community, I had the privilege of making such a choice. I had just earned my master’s degree in counseling, where I had done my ‘student counseling’ in two Boston area schools with populations that included Brown and Black and White students. In that setting, I could clearly see the need to better understand race, diversity, and multiculturalism. But I was heading to work at an island school in Maine, and my students and colleagues were almost all white. Because I was going to be in that environment, I told myself that I didn’t need to continue to study race issues in education or emphasize it in my school counseling practice—and I thought that my students didn’t need to learn about or understand race either. I’d participate in volunteer efforts in January around Martin Luther King Jr. Day and do read-alouds of books by Black authors in February as part of Black History Month, but that was about it.

As the school counselor, my main goal was to help students understand and value their identities, interests, and talents, and then assist them in developing and pursuing aligned post-secondary goals, whether it was going to college, lobstering, or doing something else. I thought a lot about equity and access to opportunity. For example, I would plan college trips around the students whose families did not have the capacity to travel. If I had wanted it to be ‘equal’, I would have simply taken all students on the same college trips. But I wanted equity, and I knew that while a few kids were traveling around visiting schools with their parents, other students were not leaving the island. So I prioritized the students who needed my help the most.

On a number of levels, I understood and tried to act on the individual and systemic barriers to positive post-secondary outcomes that were impacting my students—barriers such as poverty, lack of access to mental health and substance use disorder services, as well as gendered and restrictive cultural norms. I was doing good work and making a difference. But I was not addressing race, and that was a problem.

Understanding and discussing systemic racism

The United States is projected to become majority-minority by the middle of this century, and it is so full of racial tensions, that even young children in our small island and coastal communities are aware of them. How can we continue to tell our students that the color of someone’s skin doesn’t matter, or that we should all just be nice, and try to get along, and treat everyone the same? I want our students to be able to effectively discuss and take action against all the -isms including racism. How will our students develop these skills if the adults in their lives don’t know how to talk to them about oppression in all its forms?

There are many frameworks for understanding systemic racism and other systems of inequity, and one that I have found to be especially helpful is called “The 4 I’s of Oppression,” and they are: Ideological, Institutional, Interpersonal and Internal. This video: Legos and the 4 I’s of Oppression covers The 4 I’s of Oppression very quickly, and if this is the first time you are seeing it, I encourage you to watch it a few more times. You can find additional resources on the 4 I’s of Oppression in our resource and material folder from this year’s conference.

Do you know when I learned about the 4 I’s of Oppression? One year ago.

I was at a conference, sitting in a breakout room—a pre-COVID breakout room (an actual room with a group of people sitting close together in a circle with no masks). The workshop facilitator was reminding us of the 4 I’s of Oppression, and I was getting a pit in my stomach. Reminding us? This information was new to me. How had I never learned this before? The pit in my stomach turned into full-on nausea when she announced that the next day, we would be working on our personal race stories, and reflecting on our early life experiences of becoming aware of racial differences. I panicked. I was overwhelmed by my new learning about the 4 I’s of Oppression and extremely reluctant to tell my race story, but I am going to tell you the short version of it now.

My race story

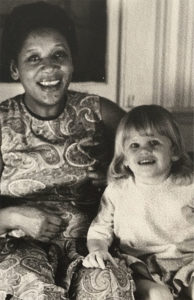

I grew up in the South, very privileged, and I had two wonderful mother figures in my life. One was my white biological mom, and one was my Black mom, Mary Jackson, who helped raise me and my siblings. In that breakout room last October, I didn’t know how to talk about the lifelong connection of love that I shared with Mary Jackson, and I especially didn’t know how to explain it to the Brown and Black educators in the room, who had a much deeper understanding of both their race and mine.

At the same time, I could not deny my relationship with Mary Jackson, who was one of the most important and influential people in my life. I quietly freaked out and stayed in that evening trying to ‘cram’ learn enough about race, so that I could share my story the next day. In a weak moment, I half-seriously asked my colleague Robin if I could borrow her race story to avoid telling mine. She wisely turned me down and encouraged me to stick with my own struggle. That day was a turning point for me, as I began to see how wrong it would be if I did not find the courage to learn how to talk about race. It now gives me a pit in my stomach to think that I even briefly considered denying the importance of, or even the existence of, Mary Jackson in my life.

As it turned out, the schedule had shifted the next day, and we didn’t tell our race stories after all, which was a huge relief, but I knew I had changed. The experience had broken my belief that I don’t have to worry about race and set me on a learning journey. The mental gymnastics that I had been doing for years to justify turning my back on addressing racism had become too uncomfortable, and I had to move. Now, I am on this seemingly harder path, but I am energized by the learning and by taking action.

The 4 ‘I’s of Oppression helped me deepen my understanding of myself, my relationship with Mary Jackson, and what it means to be white. The love and commitment that Mary Jackson and I shared was real, and in so many ways it was good for both of us, both interpersonally and internally. And at the same time, I now understand that the system in which such a relationship could exist is horrible. It is part of the social and economic aftermath of the ideology and institution of slavery, and that truth is something that I can no longer hide from. The 4 I’s of Oppression were part of Mary Jackson’s life, they are part of my life, and they are part of all of our lives.

Striving for equity

Planning this year’s Island Teachers Conference was unlike any other, both because of the changes that COVID-19 has imposed on all of us and because of the complexity of our theme ‘Striving for Equity: Rural Educators as Courageous Leaders.’ We chose the phrase ‘striving for equity’ to affirm the fact that while equity is something that we all want, it is a monumental goal and one that we must never stop striving for. In seeking presenters for the conference, we made a conscious choice to include more diverse voices than we have in years past. During the two-day event, in addition to hearing white voices like mine, attendees also heard from Brown, Black, and Indigenous people including students, educators, and many others, on a wide range of equity and justice topics.

The second part of our theme ‘rural educators as courageous leaders’ emphasizes the incredible importance of the role of our teachers. Rural educators and schools were already providing critical leadership in their small communities, and as the coronavirus hit in the spring—followed by heightened social unrest in the summer—their role became even more vital.

We quickly heard from our teachers, who expressed their desire to learn more about equity issues and their need for help in addressing these issues at school and in the community.

Inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, we also saw grassroots efforts pop up on islands and in coastal communities this summer, often led by young people stepping forward to take action at the local level.

And over the past few months, the Island Institute’s newspaper, The Working Waterfront, has run a number of articles and opinion pieces addressing race, including one in the June issue by the Island Institute’s president Rob Snyder, emphasizing the need for our communities to be more welcoming of diversity. In the October issue that just came out just prior to this year’s conference, there is a piece by Emeline Avignon, a college freshman from Long Island in Casco Bay, who reflects on her island upbringing and the need for white communities to become anti-racist.

All of this prompted us to design the 2020 Island Teachers Conference to help build on this courage—the courage of our rural educators, our youth, and all local leaders. This is an invitation to join together and either begin or further develop the skills you need to learn and teach about all the -isms, including racism, that are embedded in our culture.

Where we go from here

Brown, Black, Indigenous, Asian, Latinx—all People of Color—do not have a choice about whether they want to think or talk about race. And white people no longer have that choice either. It is hard, because many white people, including me, have not had nearly enough experience talking about race, and we need to practice together so that we can get better at it.

It is essential that the young people in our communities understand systemic racism and oppression and appreciate, celebrate, and embrace the diversity that exists on our islands, in our country, and in our world. For many of our students, school may be the best—and maybe the only—place for this learning to occur.

As rural educators, we have a moral imperative to do this work to ensure a safer, more loving, and more sustainable future for our students. That way, some day, we may all live in anti-racist communities and in a fair and just society. This is as important, or more important than, any content area or sport or soft skill that we teach. We hope that the 2020 Island Teachers Conference served as a first step in helping all of us join together as we strive for equity and become courageous leaders.

Yvonne Thomas is an Education Specialist at the Island Institute and works closely with island and coastal schools and education organizations to collaboratively develop projects, support teacher professional development, and strengthen networks to address the unique educational challenges and opportunities schools face. This story was originally presented during the opening remarks for the 2020 Island Teachers Conference on October 8, 2020. To learn more about this year’s conference, view the agenda here and check out recordings from the sessions here.