Today, we’re celebrating a delicious bivalve that grows in Maine’s cold, clean waters—the oyster. Oyster farming, and other types of shellfish and seaweed aquaculture, offer an array of benefits for our ocean and Maine’s island and coastal working communities. A recent study1 has shown that shellfish aquaculture can help meet food demand, has the potential to increase biodiversity on farms, and offers another tool for improving and sustaining our coastal ecosystem. This type of farming can also provide economic diversification for fishermen and their families and a way to continue to make a living from the water for years to come.

We asked three Maine oyster farmers 10 questions about their work on the water and what it means for our coast.

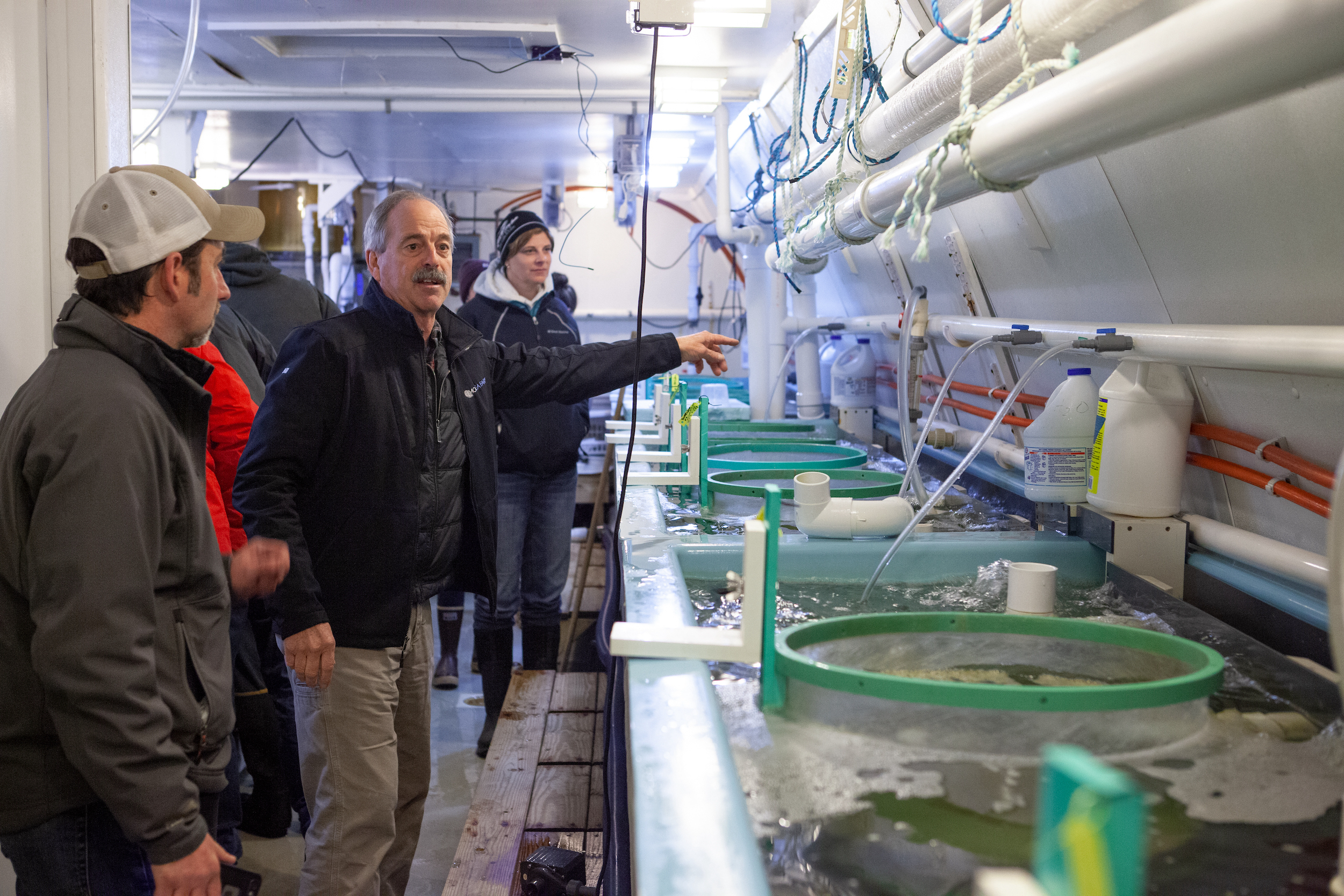

Bill Mook of Mook Sea Farm

“…it is about so much more than profit. We care about our communities, our employees, and the quality of our environment.”

Tell us about yourself and your background. Why did you decide to become an oyster farmer?

I came to Maine in 1978 as a Ph.D. student in oceanography, but after about four years realized that I didn’t want to be an academic research scientist. I took a job working in a commercial shellfish hatchery and found that what truly excited me was using my education in a very hands-on, practical way.

What makes growing oysters a sustainable way to harvest food?

Unlike many terrestrial crops, oysters eat food (phytoplankton) that is naturally available—requiring no irrigation or addition of fertilizers or other chemicals. Oysters provide important benefits to coastal marine ecosystems. As filter feeders, they improve water clarity, they reduce excess nitrogen entering coastal waters with runoff, and whether free planted on the bottom or grown in gear, they increase biodiversity.

What does it mean to you to be part of Maine’s aquaculture & working waterfront community?

Aquaculture is the latest addition to Maine’s centuries-old heritage of harvesting food from our coastal waters. Working waterfronts are vital to Maine’s character, identity, and economy. It is exciting to be part of that.

What do you think the future of aquaculture is in Maine?

Many young people have taken jobs on existing farms and started new businesses. It is a great mix of people who have grown up here or have come from away. They are passionate, smart, and hardworking, which bodes well for a bright future.

How do you think this type of work benefits the coast?

It diversifies our marine economy and represents an infusion of talent that will make us more resilient to the profound environmental changes we face. Shellfish farmers must have clean water, which makes them strong advocates for taking care of our environment.

What makes your oysters unique?

Well, like all oyster farmers, I think our oysters are the best. ? I do think conditions in the Damariscotta River produce oysters with exceptional flavor. It is also pretty amazing to think that eating Damariscotta River oysters is a tradition that goes back thousands of years and created some of the largest oyster shell middens in the world.

What’s one thing that you love about your job?

There is no one thing. I get great satisfaction from creating good jobs, from finding innovative solutions to problems, and seeing the influx of passionate young people to the field—welcome home!

What is hard about your job?

Planning for such an uncertain future resulting from climate change.

What’s one thing you want people to know about your work?

That it is about so much more than profit. We care about our communities, our employees, and the quality of our environment.

Emily Selinger of Emily’s Oysters

“I hope we see more dialog and legislation in the near future that fights to preserve this unique way of life and business.”

Tell us about yourself and your background. Why did you decide to become an oyster farmer?

I was born and raised in Freeport and have spent my entire life working and playing on Casco Bay. I traveled far and wide working as a professional sailor for a number of years, eventually getting my USCG captain’s license and running traditionally rigged schooners up and down the East Coast. I missed Maine after a certain point, though, and got tired of shipboard culture and constantly being on the move, away from my friends and family. After moving home without much of a plan, I eventually came to learn about oyster farming through my friend Amanda. I saw that I had lots of transferable skills, and therefore an opportunity to start my own oyster business.

What makes growing oysters a sustainable way to harvest food?

I think there are lots of ways to consider the word “sustainability,” and lots of ways in which, when done right, small-scale oyster farming is a highly sustainable way to grow food. Oysters are great for helping to clean up our marine environment, but that ecological service alone doesn’t necessarily make the farming of oysters sustainable. It depends a lot on how well the farm and farmer work with and fit into the waterfront they choose to be a part of, the scale on which oysters are grown in a given area, and the way in which they are marketed and distributed that make the sustainability piece really work.

What does it mean to you to be part of Maine’s aquaculture & working waterfront community?

Creating a place for myself in Maine’s working waterfront and aquaculture communities hasn’t been easy, but it has been so rewarding to build a stable business that keeps me fed, housed, and living in my home state. It’s also been rewarding to have built essential relationships with friends like Amanda, other local harvesters, as well as with my growing customer base at my regular local farmer’s markets. There’s nowhere else in the world that I’d want to live aside from here, but it can be hard for younger folks to build a career that pays well and provides a comfortable living in this state. I’m happy to be putting all my years on the water and on boats to good use and to be working for myself growing good healthy food for my community in a sustainable way.

What do you think the future of aquaculture is in Maine?

I’m not sure I have a great sense of what the future of aquaculture in Maine is. I hope, though, that it is one that continues to support many small-scale owner-operator businesses like mine, instead of shifting toward large-scale or industrial farms. Maine is such a unique place, and our working waterfronts have deep-rooted traditions in small-scale harvesting enterprises of all kinds. There’s room for many of us to work in this way, and folks stand a better chance at making a good living and working in harmony with other fisheries farming their own products than they do working as a laborer for a large company, especially if those folks are women or of any other minority population. I hope we see more dialog and legislation in the near future that fights to preserve this unique way of life and business.

How do you think this type of work benefits the coast?

I see lots of benefits to the coast in our growing aquaculture sector, provided it continues in the small-scale, family-run way. The more of us there are, the more we get the message out to the rest of the community and the world about how important it is to make a conscious effort to feed ourselves with food that is grown in a sustainable way. Additionally, owner-operators are more a part of the fabric of our local communities and any big corporate-owned farms would be, and so we in turn support many other locally owned businesses in the process of running our farms. Small-scale farmers are more likely to work in harmony with other local fisheries and waterfronts, rather than compete for space or resources.

What makes your oysters unique?

Unlike most farms, I don’t use any heavy equipment or machinery in the process of growing my oysters. They are purely shaped by the environment, which is a dynamic confluence of the wide-open Casco Bay and the constant in and out of the tidal estuary of the Harraseeket River, an area that’s been documented as being a rich and productive shellfish habitat for thousands of years. My seed comes from Maine and spends part of its life being shaped by the wind and the waves, and part soaking up the nutrients that the shallow seafloor has to offer. They are sweeter than just about any other oyster around.

What’s one thing that you love about your job?

I love most things about my job, but I most love being self-employed and I love working alone.

What is hard about your job?

My body gets tired during the summer. Weather can be challenging as well, especially when harvesting during the fall, winter, and spring months. And the threat of climate change and the small, unpredictable ways in which it’s already manifesting itself poses an ever-present sense of dread.

What’s one thing you want people to know about your work?

One of my goals is to convince as many people as I can that oysters don’t need to be a special raw bar treat. They’re incredibly good for you while also being good for the ocean, and if you seek out your local harvester or farmer, they’re also probably pretty affordable. Shucking oysters is not hard, contrary to what some folks might lead you to believe. It takes a little practice to get quick at, but anyone can shuck an oyster. They used to be an everyday food until overfishing made them a delicacy, but now that we can sustainably harvest them by the truckload thanks to the aquaculture innovations of the last forty years here in Maine, there’s no reason why we shouldn’t all be replacing some (or all!) of our weekly protein intake with shellfish. You can buy oysters directly from me at the Portland Farmers’ Market on Wednesdays or at the Bath Farmers’ Market on Saturdays, and I’m always happy to guide you in learning how to shuck.

Anything else you want to share?

It may be the year 2021 and women and minorities may be more visible than ever in industries traditionally dominated by white men, but that doesn’t mean that we have achieved “equality” in any sense of the word. We still need a huge amount of transformation in how we provide resources and training to folks who don’t come from a traditionally white, local, male space for our industry to grow in a socially sustainable way. This means recognizing the fact that there actually ARE many, many women (up to 50% of workers worldwide, by most counts) who work in the seafood industry, but who aren’t visible, promoted, or paid as much as their male counterparts.

Amanda Moeser of Lanes Island Oysters

“Diversity and diverse perspectives add the critical knowledge, skills, and capabilities that we need to transform and persevere in a time of rapid social and environmental change.”

Tell us about yourself and your background. Why did you decide to become an oyster farmer?

I grew up in Madison, Wisconsin, then traveled around the world a bit and somehow ended up in Maine. I became an oyster farmer because I wanted to have something of my own, and I also happen to be good at growing shellfish.

What makes growing oysters a sustainable way to harvest food?

In my mind, sustainability means that my business has to be economically viable in addition to providing environmental and social benefits. Small-scale oyster farming has the potential to hit on all three pillars of blue growth, but it also requires a lot of thoughtfulness, know-how, and community engagement. In my opinion, it’s not the oyster that makes the business sustainable, it’s the person behind the oyster.

What does it mean to you to be part of Maine’s aquaculture/working waterfront community?

Informal social networks have been critical in accessing the infrastructure that I need to run my business and keep evolving, key things like dockage, parking, and knowledge transfer that I wouldn’t have had access to otherwise. Then it’s my friendships with Emily, a handful of wild harvesters, and Terry and Sally at Clam Hunter Seafood who provide a sense of camaraderie and encouragement.

What do you think the future of aquaculture is in Maine?

I think aquaculture in Maine will follow a similar path as wild fisheries (aside from inshore lobstering), the salmon farming industry, and other agricultural sectors that trend towards increasing regulation and corporate consolidation unless someone steps up to facilitate more substantive, inclusive dialogues about where we want to be in 10, 20, 50 years.

How do you think this type of work benefits the coast?

This type of work benefits the coast because of the interconnectedness between fisheries, aquaculture, and other small, family-owned businesses. I buy everything I need to run my farm within a 10-mile radius of my home. I buy seed from Muscongus Bay Aquaculture. I go to Ponos/Brooks Trap, Bath Industrial Supply, Coastal Midcoast Marine, and the local hardware store for supplies. I pay my dockage at a family-owned marina and a family-owned fishing wharf (the last one left in town, by the way). In the summer, I sell oysters to a family-run seafood market, and then in the winter, I pay to store my oysters in the cold storage space that would otherwise be empty. I feed my friends and neighbors and I also give away a small portion of my profits and/or product to social, agricultural, and fishing-related non-profit organizations in Maine.

What makes your oysters unique?

My oysters are unique in a few ways. I grow my oysters off an uninhabited island in Casco Bay where shellfish have been harvested for thousands of years. I plant high-quality, diploid seed from Muscongus Bay Aquaculture, born right here in Maine. I don’t use heavy equipment or machinery and the oysters spend a majority of their life just sitting on the bottom of the ocean doing their thing before harvest, so they’re green, have a thick shell, and are really fat and happy animals. Rather than tumbling and disfiguring them into an unrecognizable, but uniform shape to match market demand, I just say “no two are alike” and customers seem to be fine with that!

What’s one thing that you love about your job?

It sounds trivial, but one thing I love about my job is my new boat. For the first five years, I ran my farm from a sinking 11′ skiff with frequent motor issues that I bought for $750. I made due and still use that boat for quahogging, but this winter I bought a larger skiff with a working motor and automatic bilge pump and it changed my life!

What is hard about your job?

The hardest part about my job is knowing that no matter how hard I work, I will never be able to own a home in the community in which I farm or live because the price of real estate is out of reach for so many of us.

What’s one thing you want people to know about your work?

It is time to make room for newcomers—women, young people, immigrants, and minorities—on the waterfront and not simply in subordinate roles, in addition to recognizing Indigenous rights to land and marine resources in Maine. I’m talking about access, ownership, and legal rights and I’m talking about transformation, not adaptation. Diversity and diverse perspectives add the critical knowledge, skills, and capabilities that we need to transform and persevere in a time of rapid social and environmental change.

Anything else you want to share?

Yes, I would like people to know that in the summer they can buy my oysters on their way down to Popham Beach at Clam Hunter Seafood in Phippsburg. It’s a family-owned seafood shop that only sells locally harvested seafood and Terry and Sally (the Clam Hunters) also have their own oyster farm.

1Comprehensive global study confirms restorative aquaculture has positive impacts on marine life; Portland Press Herald