You’ve probably heard the term “elevator pitch,” right? It’s mostly used in business circles, capturing the idea that an entrepreneur needs to be able to explain a business concept in a timeframe equal to the average elevator ride. That journey provides the ultimate captive audience, and so a clever pitch in that short time might land an investor. Well, here at Island Institute, we sometimes crave an elevator trip up Burj Khalifa in Dubai, with its 163 floors, to give us time to explain where the organization has been and where it is going.

This year marks the Institute’s 40th year. Maine’s islands and coast were very different places in 1983, yet as we reflect on those four decades, it’s satisfying to see consistent themes threading through the years.

These days, we often describe ourselves as a community development organization. What does that mean? It means we recognize how essential those units of human congregation are; community coalesces around shared economic and cultural activity, and over time, it grows its own values and learns to identify threats. Yet at the same time, community cannot thrive without change, without innovation, and the courage to pursue new opportunity, new ways of doing things.

And at the heart of it all is an idea that’s best captured in the phrase “a sense of place.” It’s a vague phrase, yes, but I think it embodies something of the shared identity people have with a community, a sentiment that joins people in loyalty and affection and even love for that place. And that love must be fierce in the face of winds from storms that sweep across the globe.

When Philip Conkling and Peter Ralston launched the Island Institute 40 years ago, they recognized that island communities, especially those not connected by bridges to the mainland, risked becoming ghost towns. This wasn’t a hypothetical risk. Conkling notes that in the year 1900, there were some 300 year-round island communities off the Maine coast. Their geographical setting made practical sense, of course. Until the 20th century, goods and people in our corner of the world were most efficiently moved by ship. New York and Boston were more accessible from Vinalhaven and Bass Harbor than from Augusta and Lewiston.

Conkling, who had trained as a forester, tells the story of being hired to do a timber survey on an uninhabited island Downeast. When fog prevented the lobsterman from picking him up, he was left island-bound for another day. He wandered around and discovered foundations from a settlement, which piqued his curiosity: Who were the people who had lived here, and what had happened to them?

Back on the mainland, Conkling asked questions at the town office, looked into records, and soon discovered that the island community had been abandoned.

So, with fewer than 20 year-round island towns remaining in Maine at that time, a mission was born—helping sustain these communities.

Conkling met Ralston on Allen Island off Port Clyde. The island had been purchased by renowned artist Andrew Wyeth and his wife, Betsy. Betsy had hired Conkling to do a timber survey and Ralston, who had grown up next door to the Wyeths in Pennsylvania, was visiting the family. Ralston had been working as a photojournalist, often traveling the world for magazine assignments.

The nonprofit was formed on Hurricane Island, itself a vivid reminder of what was at stake. In the 19th century, the island essentially had been a labor camp, with families living there to work the granite quarry, and paying the company for housing and food and other staples. As the market for granite began to disappear, the owners demanded the resident workers and their families make a quick choice—be transported to nearby Vinalhaven or to the railroad station in Rockland. It was a sad end to an unsuccessful island community.

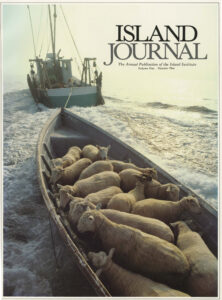

Conkling was a writer, and given Ralston’s photography experience, the two thought they’d launch their organization with a publication. Betsy Wyeth agreed to

published Island Journal in 1984, featuring the now-iconic cover

image of sheep being towed to an island.

support the effort, but with a caveat—do it well, she said, rather than produce one of those mimeographed newsletters so many nonprofits published.

And so, with Wyeth’s generous support, the first Island Journal was published in 1984 with Ralston’s now-iconic cover image of sheep being towed in a boat. Island Journal, like the organization that produced it, has evolved, but at its heart the publication still aims to reflect the richness of island culture—and that’s “culture” in the anthropological sense, not the arts (though that, too, is featured).

Several years ago, some of us decided to empty and organize file cabinets at the office, and perusing the materials within was like a trip back in time. We found several forestry plans Conkling had completed for small, privately owned islands—a way to bring revenue into the fledgling nonprofit. Early newsletters outlined the Institute’s work over the previous year; one memorable stand the organization took was to oppose a large-scale residential development on an island off Portland. “Responsible development” of the islands was what was needed, the Institute asserted.

Other publications were launched: the Island News, Inter- Island News, and finally, The Working Waterfront. The latter, Conkling has explained, was established in 1994 because the 4,500 year-round islanders needed more political clout. They needed friends on the mainland, he said, and so the newspaper covered concerns shared by island and coastal communities.

Another moment in the organization’s evolution can be seen in the archives of these publications. At one point, the Institute’s leadership wondered if accepting advertising for island real estate was undermining that “responsible development” principle. Of course not, they concluded. After all, it was islanders who began and ran those real estate agencies.

island schools through video and in-person meetings, and scholarships helped sustain

these schools.

Back to the idea of community: What are its essential elements, especially in the finite world of an island? One concept is the “three-legged stool,” whereby an island town needs a school, a store, and a post office to remain vital. Other components might be substituted, and certainly economic opportunity is critical.

So the Island Institute created education programs to assist the several one-room island schools. It established the Teaching and Learning Collaborative—TLC—to foster communication between those schools. Before Zoom became a way of life for many, children in those schools developed friendships through screens, often facilitated by an Institute staffer.

Island leadership and governance also have been challenges. So the Institute formed the Maine Islands Coalition, made up of representatives of each island who meet quarterly to discuss issues they confront.

The marine economy has always been a focus for the Institute, and remains so today. Staff work to see over the horizon to help fisheries-dependent communities prepare for downturns in certain harvests. In recent years, the Institute helped many start small-scale aquaculture businesses as a hedge against declining fishing revenue.

More than a decade ago, the Institute broadened its mission scope to include serving “remote coastal communities.” That soon evolved to include the entire Maine coast, and beyond.

One of the organization’s best strategies has been to bring groups facing similar challenges together, even if those groups don’t share a geography. Fishermen from the United Kingdom once gathered with their Maine counterparts in Rockland to share their experience with wind turbines in the North Sea. Residents of Block Island did the same as wind turbines were becoming a reality off Rhode Island. Islanders from the Great Lakes traveled to Maine to see how our islands addressed challenges.

These convenings, as we like to call them, share the lessons our communities have learned with the wider world.

And in fact, despite the broadening scope of the mission, islands remain—as former Institute President Rob Snyder used to say—our North Star, informing and guiding our work. Islands can be understood as living laboratories, or even crucibles where solutions for difficult problems are tested. How does Matinicus get rid of its old washing machines, refrigerators, and hot water heaters? How does Monhegan move away from a diesel generator for its electricity? And how do Frenchboro and Isle au Haut find enough housing for lobster crews during the summer?

In 1983, could Conkling and Ralston have imagined today’s threats of a shrinking workforce and a rising sea? In a sense, yes. Stemming the falling tide of islanders moving to the mainland was a concern back then, and fragile island environments were always on the Institute’s radar.

Could they have foreseen the Institute’s need to help island and rural coastal communities secure reliable internet? Again, in a sense, yes. Connecting communities to the wider world has always been the mission.

Another part of the Institute’s story is its board of trustees. Today, the organization is guided and grounded by a board that includes a range of thoughtful people, including a veteran lobsterman, a boat yard owner, a seafood marketer, an environmental scientist, a school administrator, and more. Their roles, often behind the scenes, are essential as we plot a course forward in this century.

And so is the leadership emerging from Kim Hamilton, the Institute’s fourth president, named in April, and the first woman to hold the post. With an impressive nonprofit background that includes work with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and FocusMaine, she agreed to take on oversight of our programs work on a temporary basis and, she says, fell in love with the organization.

Hamilton, a native Mainer, has generational ties to Chebeague Island, where she now resides.

If you boarded that elevator for the long ride with me and asked about the Institute’s mission, I would tell you an imagined story about a summer resident of, say, North Haven, driving a visitor from California into the island village. He might point out the caretaker who checks his house during the cold Maine winter months and he might wave to the postmistress who activates the family’s box for the summer. He also might nod to the lobsterman who provides his catch for family feasts, the town administrator who keeps the streets paved, and the school principal who ensures island children are well educated. And as he takes his visitor to his boat, he might introduce him to the crew that rebuilt its engine.

My imagined North Haven resident wants his island community to remain authentic, I would say, and avoid becoming a sort of gated community. And that’s what the Island Institute works at, year after year. Oh, and by the way—our imagined summer resident probably has a few copies of Island Journal on the family’s coffee table.

Tom Groening is editor of Island Journal and The Working Waterfront.

Photos by Peter Ralston, Jack Sullivan, and Island Institute staff.