“People, events, and writing of them is my bag. A weekly newspaper is an ideal way—if used to its proper potential—to do this. You are or should be at the center of the action, be able to become familiar with the business and personal interests of the people in your area, be intellectually stimulating while directing the community to better purposes and goals through articles and editorials. This is why I am here.”

—“Through My Eyes,” Dec. 19, 1968

By Tom Groening

It sounds like the plot of a period-piece film.

In 1968, the year that saw assassinations, a violent party convention, and a far-off war claiming more and more lives, a young man “from away” arrives in an isolated Maine fishing village to take over the local newspaper.

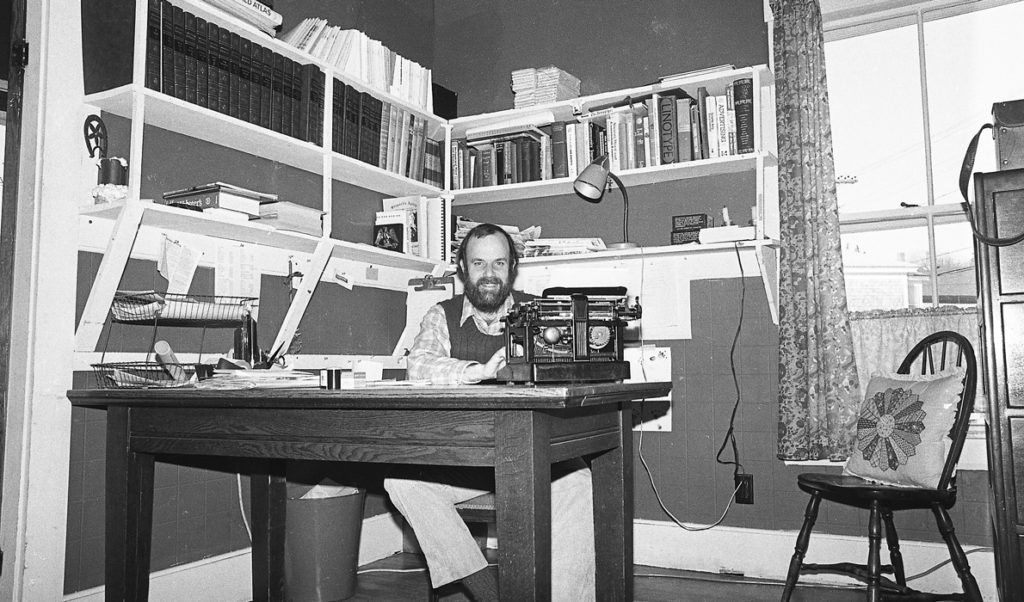

For Nat Barrows, who arrived in Stonington to purchase and run the Island Ad-Vantages that turbulent year, the expected plot twists that followed made for a rich and rewarding life. From the beginning, Barrows—now 73—wrote a personal column for the newspaper, “Through My Eyes.” Penobscot Books, a division of Barrows’ company, which now also includes the Castine Patriot and Blue Hill’s The Weekly Packet newspapers, has published a collection of those columns from the last half century.

And back to the film comparison: Reading Through My Eyes is like watching an epic film that opens in the present and then dissolves to a drama-laden past. From the beginning, Barrows is a fearless writer, disarmingly open about his values and goals, and faithful to a vision of making his often-rough-around-the-edges community better.

His work represents the very best of community journalism, even though the newspaper generated death threats and 3 a.m. calls from drunks.

The early columns reflect 1968 in all its turmoil. From the Oct. 31 issue, taking on the election that would see Richard Nixon prevail over Hubert Humphrey and George Wallace, he writes of the political atmosphere: “This could be a picture of the Italian and German situation in the late 1920s and early ‘30s.”

And as remote as Stonington was in those days, it was not immune from the grim fall-out of the war in Vietnam. The Nov. 14 issue gave emotional context to a front-page story about a fallen soldier: “Donald Bartlett of Stonington has seen 20 falls and winters. He will not see his 21st spring. … My little weekly newspaper would no longer bring a breath of Island salt air to a young man in a steamy jungle on the other side of the planet.”

And from the next issue: “The snow turned to sleet, then rain, as the sorrow turned to anguish, then tears. Donnie Bartlett was buried Monday.”

Reflecting on those now 50-years-plus in a recent interview in his office overlooking Stonington Harbor, Barrows is not focused on curating his past or recounting his successes.

But the past is on rich display in the book. Barrows writes with disdain about city life, he urges readers to see the environmental degradation around them, and he alludes to choices his community must make about its schools, urging residents to invest in their future. He also writes lyrically about the sublime joys of sailing around the island, late-night walks on the shore, and the never-ending work of carving out a small farmstead on the island’s rocky soil, raising sheep and boarding horses, cutting firewood and growing gardens.

MAINE CONNECTION

Though he grew up in Clinton, Conn., Barrows proudly notes his great-grandfather lived in Gorham.

“My mom and I would come up from Connecticut and spend a month or so there,” at the 1840 family home. “The culture and environment of the state of Maine really appealed to me.”

In a short time, his hometown grew from 1,200 residents to 10,000. “I didn’t like what was happening,” and he felt the tug of the back-to-the-land sentiment shared by many of his peers, and so he scoured Maine for land.

“I wanted to be my own boss,” Barrows remembers, and so when he stumbled across an advertisement for the sale of the Island Ad-Vantages (which is reproduced in the book), he took the plunge.

“I was open. I was ready for anything. For the price of a used car,” he says, the paper was his.

Newspaper work was not new. Barrows had been a sports reporter for his high school paper, he’d written for the college paper while attending the University of Denver, and been a copy boy at the Rocky Mountain News. And his late father had been a journalist who was killed in an airplane crash while working in Asia.

Still, a young man from Connecticut arriving in Stonington in 1968 might have looked like the journalistic sin of “parachuting in,” Barrows admits.

“I was an immigrant here. The quarries had closed, fishing was struggling, people were leaving.” The town probably had little use for his youthful idealism.

“I got shunned by a lot of people,” he remembers. Passing an acquaintance on the sidewalk who did not acknowledge his greeting, “I had an epiphany.” Giving himself a pep talk of sorts, he remembers thinking, “You’re doing this for your community. I’m not here to be liked.”

Barrows served as a town selectman for a time, a move that might raise eyebrows today among even community journalists, but he defends that service. He insulated himself from editing or directing any of his paper’s coverage of town government, he says. Taking on the role was another way to help push Stonington and Deer Isle forward, he explains.

“Our job is to present people with the facts—present then with unbiased information,” he says. “And let it go. What the people do with it is up to them.”

One story featured photos of sewer outfall pipes along the shore, aiming to move residents to action. “One of my missions is to make people notice. They were taking the environment for granted,” he recalls.

“The thing I love about community journalism is you live with your sources,” he says, which ensures accountability. Like many in the business, he laments the denigration of the press at the hands of President Donald Trump and former Gov. Paul LePage.

Barrows added the Packet to his company in 1981 and the Patriot in 1990, but, like the industry in general, “It’s struggling.”

Stonington seems to have struck a balance between lobstering and tourism, but Barrows sees troubling signs. A waypoint was passed in the 1980s, he says, when the number of real estate agencies exceeded the number of lobster buyers. “Land became a commodity,” he says, and waterfront is now sold by the foot.

One change Barrows made to the paper on arriving was to begin capitalizing “island” when it referenced Deer Isle. The idea was to underscore the notion, “We’re islanders and we’re all in this together. The capital ‘I’ is important.”

At the close of our interview, he brings up the moon landing 50 years ago, and the photo of Earth that gave people a sense of the fragility of our world. Island life is understood similarly. “It’s an emotional sense of place. Your boundaries are set by Mother Nature.”

Barrows will speak, read, and sign copies of Through My Eyes at Chase Emerson Memorial Library at 17 Main Street, Deer Isle, beginning at 4 p.m. on Aug. 21.