By Susie Arnold, Ph. D. and Heather Deese, Ph. D.

As the warmth finally starts seeping into our bones, the grass greens up and flowers bloom, other signs of spring emerge in our harbors and rivers: the migratory and river-run fish. As anglers dig out rods, reels, lures, and flies—or jigs made up like wacky metal Christmas trees—the fish are making their way north and east. And the lucky amongst us start looking forward to smoked mackerel.

The arriving schools come from all over the eastern seaboard of the U.S. and Atlantic Canada.

The shad that will make their way through Saco Bay or Penobscot Bay and up into the rivers this spring and early summer to spawn likely have spent 4-6 years offshore in large schools gathered off the Carolinas, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and other spots in between.

Mackerel arriving for seasonal feeding may have traveled all the way from Florida. Striped bass likely are arriving from winter spawning grounds in Chesapeake Bay, or in the Hudson or Delaware rivers. While some fish are here to breed, and others to feed, all are food for someone, or something else along the way.

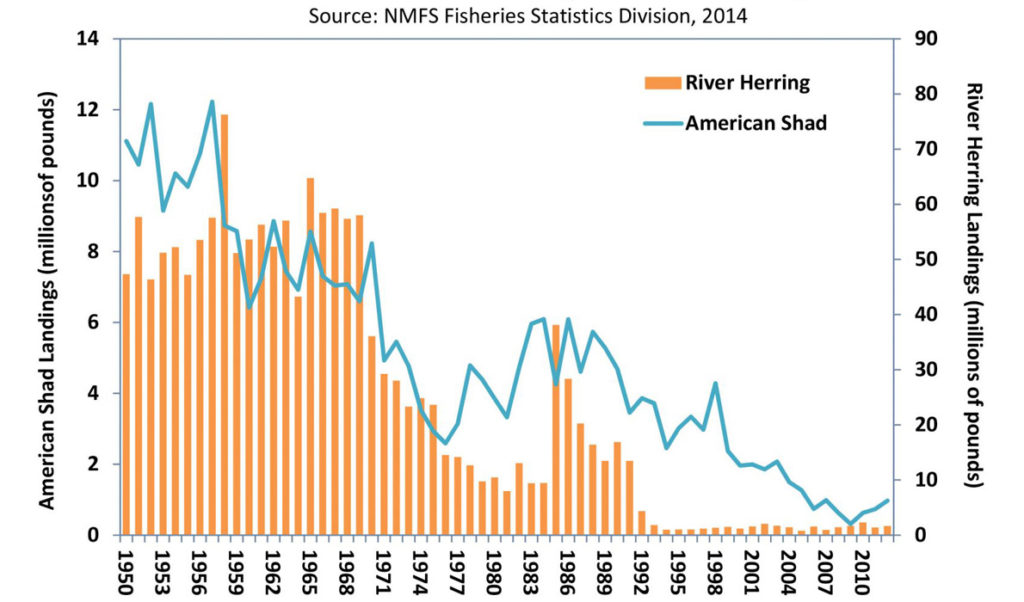

But the numbers of these animals plying our shores and rivers have decreased so precipitously over the centuries that it’s almost impossible to comprehend what spring and summer would be like if fish populations were as they once were.

The populations of river-run fish started decreasing dramatically in Maine as long ago as the early 1800s, due to dams and pollution, as well as fishing. The populations of bluefish, striped bass, and mackerel decreased dramatically in the mid-20th century, with growth of mechanized fishing fleets.

Today, we are in the midst of clean-up and rebuild, with one clear success in striped bass, and a lot of hope for the river-run herring family of fish, including blueback (river) herring, alewives and shad.

The credit for rebuilding the striped bass population goes to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, a formal partnership created in the 1940s through which the states from Florida to Maine create shared regulations for fish whose migrations don’t respect state boundaries. The commission acted after the striper populations hit rock bottom in the early 1980s. The highly controversial decisions, which put in place dramatic fishery restrictions, caused real economic hardship for fishermen. But the wisdom of the decision shines through the results. The stripers recovered, and a much larger population now supports a vibrant recreational fishery and a modest commercial fishery.

In efforts to restore populations of shad, river herring, and alewives, as well as Atlantic salmon and Atlantic sturgeon, an incredible amount of work has gone into the restoration of river habitat in Maine in the last two decades. Multi-year, multi-partner projects have removed large dams on the Kennebec and Penobscot rivers, and federal funds have helped the state wildlife agencies and local communities install or upgrade fish ladders and fish lifts (that’s right, we have fish elevators on our rivers).

Government efforts also include trucking fish from below dams to upriver habitat that is expected to be fruitful for spawning. After many of the large dams came out, changes were evident almost immediately, and there is great hope now that our river-run fish in Maine could come back in spades—and feed eagles, seabirds, seals, and many of us.

Dr. Heather Deese is the Island Institute’s executive vice president. Dr. Susie Arnold is an ecologist and marine scientist with the organization.