From left, College of the Atlantic President Darron Collins, New York City architect Susan Rodriguez, Andrew Davis, who is the Shelby Cullom Davis Charitable Fund lead advisor, and Timothy Lock, a management partner with Opal, the architecture division of GO Logic in Belfast. PHOTO: LAURIE SCHREIBER

From left, College of the Atlantic President Darron Collins, New York City architect Susan Rodriguez, Andrew Davis, who is the Shelby Cullom Davis Charitable Fund lead advisor, and Timothy Lock, a management partner with Opal, the architecture division of GO Logic in Belfast. PHOTO: LAURIE SCHREIBER

By Laurie Schreiber

The clouds and rain broke just in time for College of the Atlantic “groundbreaking” of its new Center for Human Ecology.

The May 25 event wasn’t really a matter of breaking ground, since contractor E.L. Shea Inc. of Ellsworth had already begun site work, on the northern side of the campus, for the 29,000-square-foot facility.

But scores of people enjoyed warm sunshine while they viewed a massive hole in the ground that portended the rising of a state-of-the-art structure designed to fit within the lawns, woods, and harbor vista beyond.

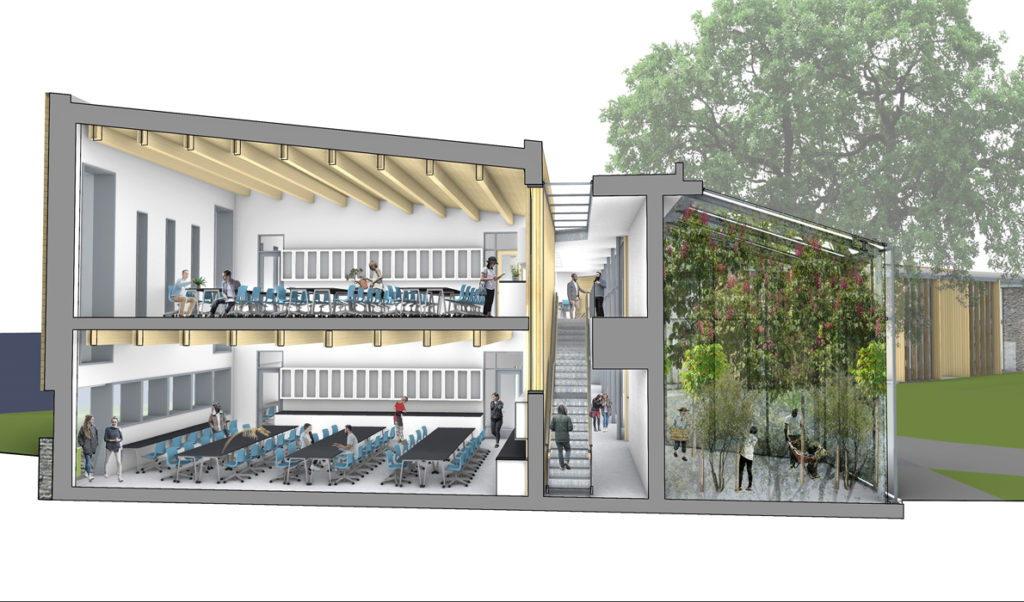

The building—to house science laboratories, flexible lecture halls, faculty offices, art and design studios, a teaching greenhouse, and gathering spaces within a two-story space enclosed by glass façades—is designed to passive house standards, which means it’s expected to achieve at least an 80 percent reduction in energy consumption versus comparable code-compliant construction.

The idea for the new center is at least four years old, dating back to the college’s 2015 strategic plan, said the college’s president, Darron Collins. However, the college has needed new space for decades, he added.

The center is the first major construction here since a 1983 fire destroyed a building that housed the library, most classrooms, and faculty offices. Renovation subsequently converted an adjacent carriage house and garage into an arts and sciences building. Two marquee buildings were constructed in the late 1980s to contain a theater, classrooms, offices, library, and more. As enrollment grew through the 1990s, with 350 students and 35 faculty members today, COA began building small dormitories.

The latest project conforms with the college’s focus on “human ecology,” an interdisciplinary study of the relationship between humans and their natural, social, and built environments. That’s led to carbon neutrality initiatives that garnered recognition as the nation’s No. 1 Green College for 2016, 2017, and 2018 in The Princeton Review.

Architects for the project are the New York City firm Susan T. Rodriguez, and Opal, the architecture division of GO Logic in Belfast. They worked with staff, students, and faculty for more than a year to develop the design.

Passive design begins with factors like site selection and solar orientation to help optimize energy performance. Construction of a high-performance envelope incorporates super-insulation, tight air seals, triple-glazed windows, and added ventilation, said Opal architect Timothy Lock.

For a Maine home typically spending $5,000 per year on heat, the approach can result in a heating bill of $300, he sad.

“Imagine that scaled up to 27,000 square feet,” he said.

The approach uses local and recycled materials. Given Maine’s huge forest resource, he said, it made sense to use wood for exterior cladding, interior finish, and even insulation. The project will incorporate “mass timber,” an emerging engineered wood product said to provide a lighter carbon footprint and greater flexibility than other structural materials.

Other new technologies include a sensor to automatically turn lights on and off depending on daylight levels. Rooftop solar panels will likely get the building down to zero energy consumption, Lock said.

“Bird safe” glazing, optically clear to humans but opaque to birds, is expected to prevent bird strikes. Lock said he expects the project to become a demonstration study for the material’s use, as part of American Institute of Architects Maine’s committee on the environment advocacy for bird-safe glass in all Maine public building.

The center is the $13 million first phase of construction expected to transform the waterfront campus, according to a January press release. Subsequent phases include a new welcome center and entrance plaza.

The project, including an endowed maintenance budget, is financed through philanthropy. Funding is made possible by lead gifts from Trustees of the Shelby Cullom Davis Charitable Fund and Trustees of College of the Atlantic. Completion is expected by September 2020.