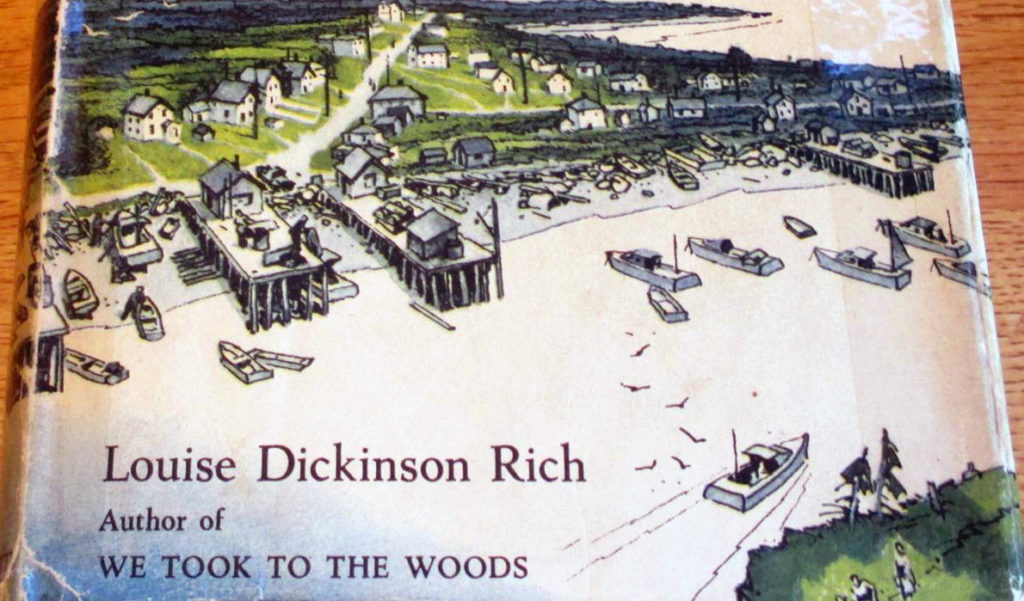

The Peninsula, by Louise Dickinson Rich (1958, Lippincott)

By Tom Walsh

Great books often serve as literary time machines, taking readers back to the way things were.

Anyone interested in the ongoing 300-year evolution of modern history and culture of Downeast Maine should make an effort to find what is a sometimes hard-to-find copy, a 1958 memoir by Louise Dickinson Rich. The Peninsula recounts the summers that the book’s “from away” Massachusetts author spent hunkered down within a no-electricity, no-plumbing log cabin on the Gouldsboro Peninsula’s Cranberry Point in Corea.

Louise Dickinson Rich was more-than-less a stranger to the fishing community of Corea and no-small curiosity to the remote harbor’s “old stock” multi-generational families. But she was not a stranger to everyone. Rich had written a best-selling book in 1942—We Took to The Woods—which recounted the years she and her spouse spent at “Forest Lodge,” their remote cabin near Lake Umbagos in Oxford County.

Soon after she arrived in Corea, someone recognized Rich’s name, having read one of her books or a magazine piece. After Readers Digest published Rich’s short piece about Corea, giving summer refuge to a writer from away didn’t sit well with some of the locals.

One day a driver delivering mail to Corea confronted Rich:

“Now look here, Mizz Rich,” she recalled him saying. “We don’t want no book written about us. We’re ignorant and we know it, but we got feelings like anybody else. We don’t like to be twitted about our ignorance by summer people, in print or out of print. You treat us decent and you won’t find anybody, anywhere, kinder or more helpful than we are. But start making fun of us, and we don’t like it. It hurts. We’re no better than anyone else, but neither are we any worse. We’re just hard-working people, trying to get along the best we can. Damn it, we ain’t ‘quaint.’ I’ve read books about some of the towns along here, and I don’t like them. I ain’t going to have that happen to us.”

Rich was no fan of the “rusticator” movement, which embraced coastal Maine as vacationland—a summer refuge, a seasonal escape from the heat, humidity, and the stresses and strains of earning too much money while living in East Coast cities like New York, Philadelphia, and Boston. She watched seriously wealthy rusticators (think: Rockefellers, Fords, and Campbell Soup heirs) invade and overwhelm Mount Desert Island, swallowing whole Bar Harbor, Seal Harbor, and other fishing communities.

Those seriously wealthy from Philly, hoping to put at least some geographic distance between them and Bar Harbor’s New York-centric elite, settled eight nautical miles across Frenchman Bay. During the 1890s, they arrived, money in hand, to the once-sleepy fishing community of Winter Harbor.

There—money still in hand—they created the still-enduring Grindstone Neck encampment of spare-no-expense, oceanfront “cottages,” mansions that now sell for as much as $4 million-plus. In the process, Grindstone Neck’s founding rusticators converted Winter Harbor’s working waterfront lobster landing into what remains, 100-plus years later, a members-only yacht club.

“In Winter Harbor there are luxury homes, art galleries, and a store that carries S.S. Pierce products and Pepperidge Farm bread,” Rich wrote two generations ago. “No one there ever sets out (lobster) traps. They were all too busy washing the windows, clipping the hedges, and raking the driveways of the wealthy. I don’t blame them for choosing this easier means of making a better living, but I cannot help feeling that they have sold their birthright for a mess of pottage. … They have thrown away their independence.”

The remnants of Rich’s observations endure. She, however, does not. She passed at age 87 in 1991, in Massachusetts. Heart failure. Family by her side. Over the years, she researched and wrote 23 books for adults and children, covering history and nature. Her essays and stories appeared in countless magazines.

Rich predicted that the inevitable arrival of the rusticators would forever impact Corea and its fragile culture. Rich regarded Corea as a “last frontier, an anachronism.” It was the kind of place that, had it never existed, Norman Rockwell would be compelled to paint it anyway.

In her final analysis, Rich is more than a bit prophetic.

“When the last lobsterman hauls his last trap and turns his boat over to fishing parties from the city, when his sons turn from the sea to a full-time caretaker’s job, when his wife stops knitting bait bags and opens a gifte shoppe, and when (the local) store is transformed into a gaudy supermarket, something that was America will die.”

Tom Walsh is long-time journalist who lives in Gouldsboro.