In the 1980s and 1990s when I was teaching at Unity College, the outdoor recreation professors drilled a memorable sentence into every generation of student: “The woods don’t care.”

It meant that along with being remarkably beautiful, the forest is remarkably dangerous. The oaks and cathedral-like firs do no more than stand there when you’re lost and running out of daylight. They stand there all night, too, unmoved, and on into the next morning.

It’s hard to think of a tree as a threat. It just doesn’t care. But its inhabitants, like ticks, are a clue about the warning’s depth. They can scare the pants off you.

Fourteen species of ticks have been identified in Maine, though four of those are extremely rare. They’re small. Some, like the dog tick, lone star tick or squirrel tick, can be up to a quarter-inch wide before feeding, but a lot of them, like the deer tick, are just lumbering specks, an eighth of an inch or less.

If one finds you, it burrows into your skin and drinks your blood. It can inject bacteria into you. If you don’t carefully tweezer it off your scalp or ankle, the body tears away and the maw gets stuck. The whole head stays in your skin, digging deeper. Bad infections can follow.

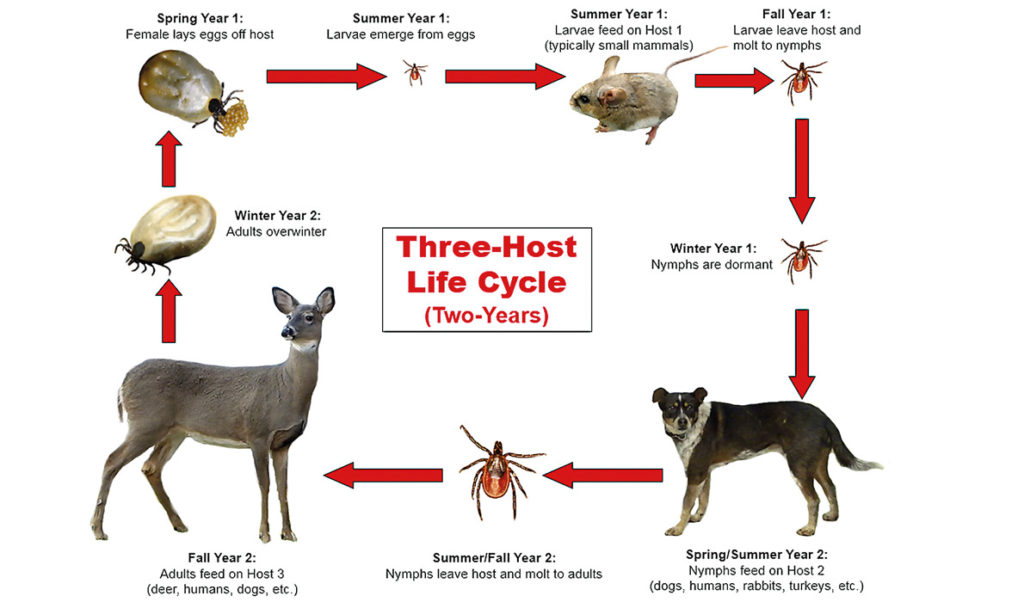

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is transmitted by dog ticks, though no cases of it, so far, are known to have originated in Maine. The worst of the tick-borne illnesses is Lyme disease, which is transmitted primarily by deer ticks whose larvae have fed on mice or chipmunks, or adults on white-tailed deer, that are infected with a corkscrew-shaped spirochete bacterium, Borrelia burgdorferi, that is the culprit. Lyme disease usually starts with a rash, fever, headache, and muscle or joint pain. After weeks the pain can get worse, and after months mental instabilities can set in.

But the ticks don’t care, and neither do the deer and small mammals who feed the ticks, and neither does their habitat.

Many years ago, in 1981 it was—about the same time Dr. Willy Burgdorfer was zeroing in on the deer tick as the vector for the mysterious disease that had broken out among kids in Lyme, Connecticut, in the 1970s—some friends and I went camping on Little Chebeague Island in Casco Bay. We walked around the beach from the ferry stop on Big Chebeague and at low tide crossed the sandbar to Little Chebeague, which at that time was overgrown and wild. We found a huge, gorgeous oak tree in a grassy clearing on the west end of the island and set up our tents under it.

While my friends took a camper’s nap, I read for a little while, then got restless and walked down to the rocky beach to ruminate on the beauty of Maine and its seascapes—the wild rose thickets yellowing in the September sunlight, the glistening blue water. Signs of the divine.

Standing on the silent beach, looking across the water toward Clapboard Island, I took off my hat and ran my fingers through my hair. (It was a long time ago.) I felt a scab. Odd. It came loose. Then I felt another one. It came loose, too.

On my neck was another one, and wondering what the hell was going on I brushed it away. I took off my shirt and saw motion in the collar and seams. Ticks. Multilegged. Crawling. Ravenous.

I shook out the shirt and looked in my hat—the inside band was teeming. I took my pants off, and in the seams and zipper were ticks, ticks. I brushed, flapped and picked until they seemed gone, and then I stripped and dove into the cold salt water and stayed under to soak off whatever monsters remained.

I don’t know, it must have worked. I got dressed and walked back to tell my friends. We had a collective vision of ticks—maybe they were dog ticks or squirrel ticks—dropping like paratroopers out of the oak tree to feast on us and leave us for dead.

The woods, we reflected even then, simply do not care.

Dana Wilde of Troy writes the Backyard Naturalist column for the Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel newspapers. His recent book is Summer to Fall: Notes and Numina in the Maine Woods, available from North Country Press.