It’s no longer a matter of “if,” but rather “when.”

Maine’s 3,500-mile coastline is being buffeted by higher seas, bigger tidal surges and storms, all the result of climate change.

Preparing for these impacts was the theme of a conference co-hosted by the pro-planning group GrowSmart Maine and the Island Institute (publisher of The Working Waterfront) on Dec. 9.

Over the last century, seas have risen 1.8 millimeters each year on average, said Peter Slovinksy, a marine geologist with the state Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry and a conference speaker. But that rate has doubled in the last 20 years.

Portland’s average increase of 1.9 millimeters over the 20th century is now 3.3 millimeters, he said. Bar Harbor and Eastport saw slightly higher increases over the second half of the 20th century.

“We’re rising faster in the short term,” Slovinsky said, with spikes observed in 2009 and 2010.

The cause of those higher seas includes three primary factors. Glacier melt and freshwater run-off from land accounts for half of the rise.

Warming seas expand, and that accounts for another 30 percent, Slovinsky said.

Another 10 percent is attributed to changes in the behavior of the Gulf Stream, which now “sloshes to the west” against New England’s shores. Those changes also allow storms out of the northeast “to come right up our coast,” he added.

The bottom line is that nine of the highest sea levels observed in Maine were seen in the last decade, he said. One way to put the potential impacts in context is that with 1-foot of sea level rise, today’s once-in-a-century storm becomes a once-in-a-decade storm.

Jeremy Gabrielson, a conservation and community planner at Maine Coast Heritage Trust who was a panelist at the conference, said his organization is working to secure land near saltwater marshes.

“Tidal marshes are dynamic natural systems,” he said, “and are very dependent on sea levels.”

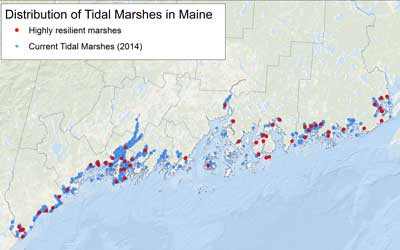

A map shows the distribution of tidal marshes, which are key in absorbing storm surge.

The land trust has been studying “marsh migration,” the idea that as saltwater rises and covers existing marshes, the areas farther inland should be unencumbered by development to become the new marsh. It’s critical to maintain marshes because they absorb and hold storm surges, protecting inland infrastructure.

The island town of Vinalhaven is studying the vulnerability of its downtown and working waterfront infrastructure to sea level rise; the town was represented at the conference by selectman Phil Crossman.

Another speaker, Jon Edgerton, an engineer with the Wright-Pierce firm, urged participants to assess which elements of their community were at risk before a catastrophic event. FEMA—the Federal Emergency Management Agency—has set standards for “flood proofing” residential and commercial structures, he added.

In answer to a question about ongoing waterfront access, Nick Battista, director of marine programs for the Island Institute, said fishing piers would have to remain on the shore, but in planning, municipalities should consider building new police stations and town halls on higher land.

A participant at the conference asked about the posture the incoming Trump administration might take on sea level rise. Battista suggested a local response.

“Here on the coast of Maine, we’re going to see sea level rise, and we’ll have to respond whether the federal government helps us or not,” he said.

Slovinsky echoed that view, saying, “We’re planning for climate change. We’re planning for municipal resiliency for sea level rise.”