A land map of the United States reveals a patchwork of federally protected areas, while a map of the Atlantic Ocean, until recently, had no protected areas. That changed in September when President Barack Obama set aside an ecologically rich swath of waters southeast of Cape Cod for a new national monument.

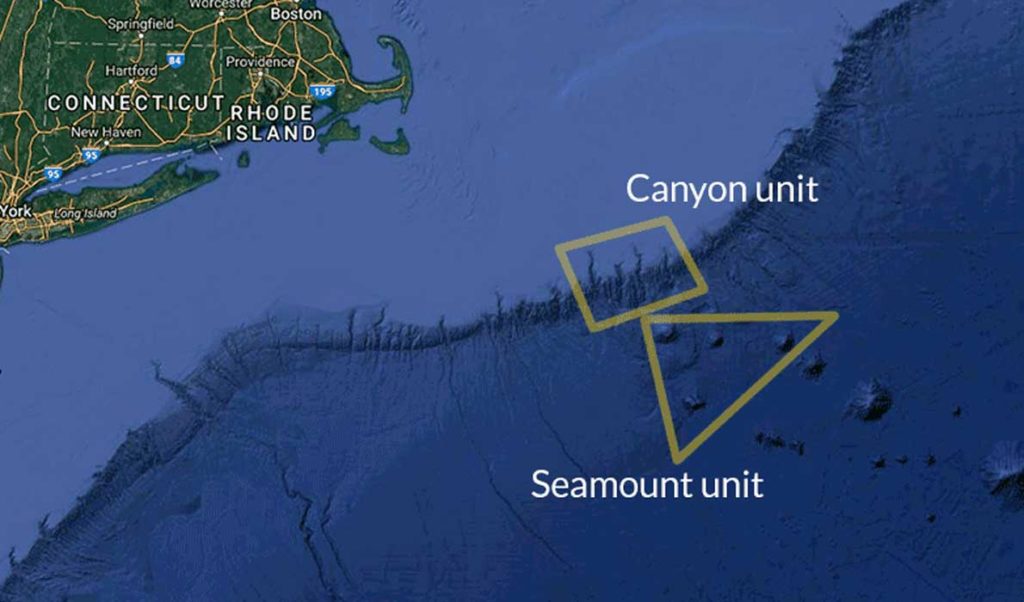

By executive order, Obama created the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts National Monument which bans commercial fishing, mining and drilling within a 4,913-square-mile area.

The monument area is known as a hotspot of biodiversity, largely because of the richness of its topography. Within this area are canyons deeper than the Grand Canyon, high underwater mountains and tree-like cold water coral, all of which shelter many healthy populations of sea creatures.

The creation of the national monument comes a year after 145 marine scientists wrote supporting its creation. The move is being hailed by environmental organizations as a way to safeguard biodiversity.

“We think that in the long run it’s going to be very important,” said Peter Shelley, who serves as senior counsel with the Conservation Law Foundation Massachusetts.

The protected area could very well become an ark of biodiversity during a time of ecological disruption in the adjacent waters of the Gulf of Maine, Shelley argued. If the sea life in the protected area is not subject to stress from fishing or other commercial activities, that might strengthen genetic resiliency, and this could be important should stocks collapse.

“They might be less susceptible to ocean temperature than the general population species,” Shelley said.

However, organizations representing Maine’s fishermen are frustrated by the move to create the national monument.

They worry that a prime fishing area not included the monument, Cashes Ledge, could be handled similarily by another president. Cashes Ledge has already been temporarily closed by the New England Fishery Management Council. Fishery stakeholders say Obama’s action cut them out of the process of managing fisheries, and worry about the approach expanding.

Ben Martens, executive director of the Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association, said the move has disrupted a ten-year process to create sustainable fishery management plans.

“For us, the concern is that you moved what had been a public process to a closed-door process,” Martens said. “That’s very concerning for fishermen who understandably feel like they are on the losing end of many regulatory decisions.”

Shelley, however, counters that fishery management plans are primarily focused on maintaining sustainable fisheries, not on maintaining the overall health of the Gulf of Maine. That’s why it’s necessary for the president to have the authority to create protected lands independent of the fishery management process, he said.

“This was perhaps a shock, but it is a public ocean and the president has the authority,” Shelley said.

It has become a recent tradition among outgoing presidents to create national monuments in the waning days of an administration, but the power to do so is more than a century old. Theodore Roosevelt signed into law the Antiquities Act, which allows presidents to create national monuments to protect historical sites or environmentally-sensitive lands. Unlike the 1916 law that created the national park system, the Antiquities Act does not require the president to seek approval from Congress to create protected land.

Since these monuments were created by executive order, they can be altered by succeeding presidents; Obama, for example, expanded a monument in the Pacific Ocean created by President George W. Bush.

There is some debate over whether the law also gives presidents the power to undo monument designations; in either case, it has never been done. Instead, critics of the law in Congress perennially try to pass bills to modify or repeal the Antiquities Act, with no success.