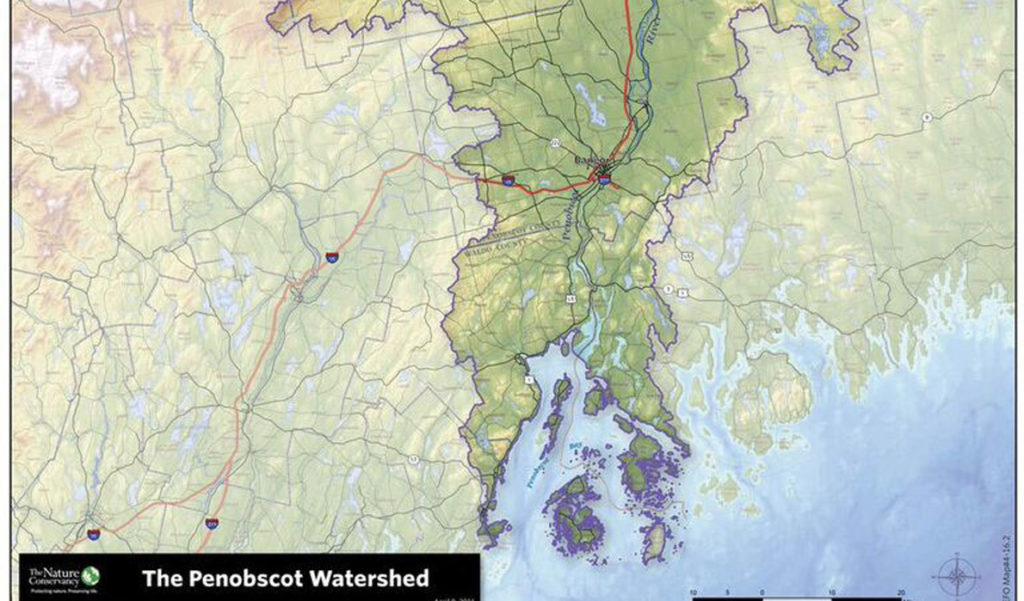

On the map of Maine, Penobscot Bay lies at the midpoint of the coast. It resembles a fulcrum on which the northern and southern halves pivot.

On the map of the Penobscot watershed, which was used throughout the venue that hosted Penobscot Watershed Conference on April 9, the image looms even larger. Rain falling near both the Quebec and the New Brunswick borders could end up in the river and bay. Almost all of the I-95 corridor north of Bangor lies within the watershed.

Instead of a fulcrum, the watershed map looks like a tree whose spreading branches are drawing sustenance from the bay and river that share a name.

Bob Steneck, a professor in the school of marine sciences at the University of Maine, said the Penobscot Bay estuary is the largest ecosystem in Maine.

“Our lives are so affected by so much of the watershed, up and down the river,” said Chellie Pingree, Maine’s 1st District representative to Congress, speaking at the conference’s opening session.

“We know this is a critically important region to the rest of the state,” she said. “People care deeply about the health of the bay because our economies are built on tourism or fishing.”

Break-out sessions explored the watershed and bay’s marine and forest economies, the environmental health of lakes and streams, climate change and recreation.

Decisions from the past have created the current environment, speakers said, as scores of dams on the river system and scores of weirs along the coast reduced fish populations. So did fishing practices.

But change is possible.

Curt Spalding, EPA administrator for New England, said the waters of Boston Harbor were among the most toxic in the region in the 1980s, and now the city’s beaches are among the cleanest. Environmental problems are less visible, though.

“We used to be able to do things with a court,” he said, going after one large polluter. Now, there are many small discharges into the waters.

A changing climate bringing higher seas and bigger storms is another pressing problem. How will communities protect low-lying infrastructure, such as wastewater treatment plants, he asked. The “pipe and treat” approach may no longer work, Spalding said.

“For most Americans, climate change is a matter of fact,” he said.

Pingree, in her remarks, couched climate change in very local terms. A long-time resident of North Haven island, she said sea-level rise is “going to be devastating for the members of the communities in Penobscot Bay.”

Seas predicted to be 3-feet higher by the end of the century would put 10 percent of North Haven’s developed community underwater, she said. “That’s our ferry terminal.” J.O. Brown’s boatyard is “gone.”

The fact that the Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 95 percent of the world’s saltwater is “perhaps the scariest number I’ve heard in a long time,” Pingree said.

UMaine’s Steneck compared the rivers and streams that empty into Penobscot Bay to the human circulatory system. Parts of the watershed blocked by dams are unhealthy for the system, just as clogged arteries are. From 1800 to 2000, an average of one dam a year was built in the watershed, he said.

In one of the break-out sessions, Ted Ames of Penobscot East Resource Center recounted how Vinalhaven fishermen in 1919 once landed 250,000 pounds of Pollack in a single day, but by 1935, fishing in the upper bay had collapsed. By the 1950s, cod and haddock were gone from the lower parts of the bay, and by the 1990s, the entire fishery was gone from the region.

Pingree issued the call to action in the face of new problems like ocean acidification and old ones like fishery collapse. “There are no big pots of federal money” to deal with these issues, she said, but leaders today must address these challenges.

“If not, our children and our grandchildren are going to be really angry at us.”