The caption on an earlier version of this story incorrectly identified the preferred route for a new bridge.

By Tom Groening

EASTPORT — Drive around the picturesque village of Eastport and you’ll see references to Moose Island. That’s because until the 1930s, when an ambitious but unrealized tidal power project built a causeway linking it to the mainland, Eastport was an island.

Another ambitious project being talked up by boosters of the city’s port would make Eastport an island again.

Chris Gardner, director of the Port of Eastport, says the shipping facility’s growth means another route for truck traffic is needed.

“There is going to be a time when we reach a limit where we’re not going to be able to go,” he said of increasing vehicle traffic to and from the port.

The most truck trips seen to date are 18,000 a year, but a plan to ship more wood chips could add 4,000 truck trips, pushing the current annual total above 18,000.

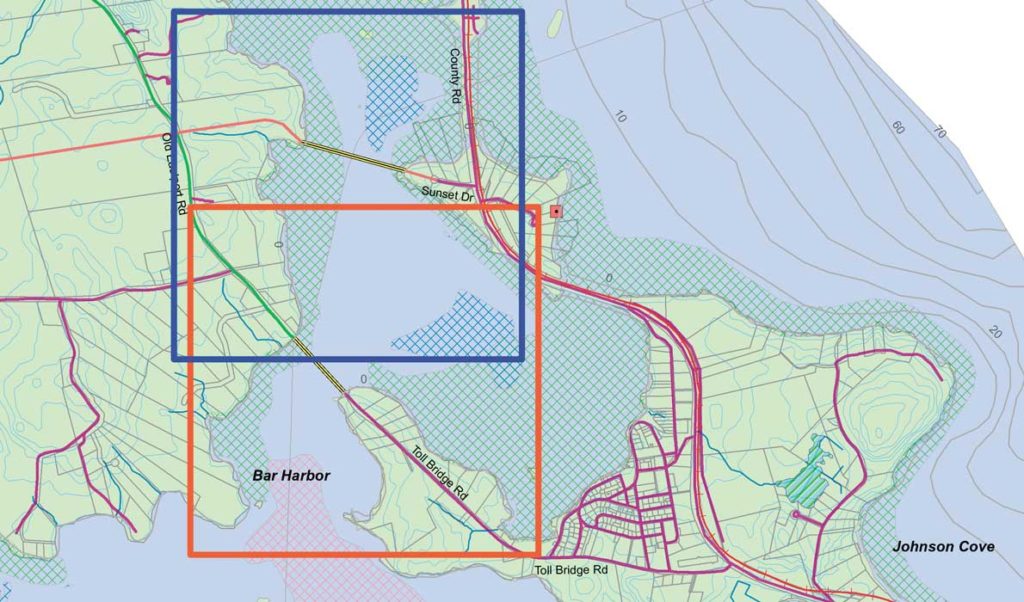

The plan Gardner’s touting would have a bridge built from the Carlow Island part of town to the mainland.

Once the bridge is built, the causeway over which all vehicle traffic now travels to get to Eastport—to both the downtown and the port facility—would be breached.

Gardner grows more and more enthusiastic as he enumerates the benefits of such a project.

The port’s truck traffic would no longer pass through the Passamaquoddy tribe’s Pleasant Point reservation and the reservation would no longer be cut in two by a road. By breaching the causeway, water would again flow through a cove that has languished since the tides were cut off.

But most important, a new bridge, with a possible rail line, could help Gardner and others grow the port facility, which they believe has enormous potential.

“We are going to be the loading dock for the East Coast,” Gardner says, hanging that goal on some key assets, such as the 64-foot-deep water at low tide near the pier and 100-foot depths in the ship approach area. That 64-foot depth exists naturally, without the need to dredge, and greatly exceeds Maine’s other two deep-water ports, in Portland and Searsport.

“We are dredged by the good Lord, two times a day,” Gardner quips, the result of 20-foot tides.

And it’s more than bragging rights. Ships have gotten bigger in recent years—one class is known as Panamax, meaning they are now the largest that can traverse the expanded Panama canal—and they need deeper water in which to maneuver and dock.

The port lost rail access in the late 1970s and mid-1980s, when operators abandoned two sections. Transportation experts have long said the port needs rail access again to grow, and Gardner agrees, though it might take some time to build a new line.

But his vision for the bridge, the new road connecting Eastport to the mainland and a possible rail line are not as unlikely as they might seem. The favored route that Gardner and others have identified for the bridge and road cross three properties once they meet the mainland and link with U.S. Route 1. The largest of these is owned by the tribe, which supports the plan, and the owners of the other two “are willing participants in this project,” he said.

The parcels are relatively undeveloped, and the new road is “actually a way to move truck traffic away from residential areas.” No use of eminent domain is anticipated.

Still, Gardner knows that the project faces steep hurdles. The cost of the bridge and road, as he envisions the work, could top $150 million. With rail and upgrades to the port facility, the project could total $400 million.

The bridge would be 2,400-feet long, a football field length longer than the Penobscot Narrows Bridge in Bucksport.

“We’re in the very early stages of this,” he said, and the project would proceed in phases.

But in addition to the cooperation of the landowners, other factors are on the project’s side.

Gardner notes that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers would likely approve of the plan to return the tidal flow through the man-made causeway. “This is an environmental remediator,” he said.

Even more leverage, perhaps landing federal funding, could come with the tribe’s support, he said, and Washington County’s status as one of the poorest regions in New England.

“There’s a lot of constituencies served,” he said.

Private money could be invested, too, given the delays seen in ports in Los Angeles and Long Beach, Calif. Gardner notes that 95 percent of the world’s goods are shipped by sea, and that ships are the cheapest and least fuel-intensive transportation mode as further supporting developing Eastport’s terminal.

“We’re the deepest natural seaport in the continental United States,” Gardner asserted, yet that port is not served by a road adequate for the truck traffic that might come. Eastport could become a niche port or even a major player in shipping, giving access to the U.S. East Coast and Midwest.

“It’s a return to who we are,” Gardner said of growing the port.

Coverage of Washington County is supported by a grant from the Eaton Foundation.