The smoking gun on climate change is, well, the smoke. Or at least carbon pollution. But the real smoking gun, said activists from the Center for Climate Integrity and Union of Concerned Scientists, is that the fossil fuel industry knew what impacts carbon pollution would have on the climate.

And beyond casting blame, these groups are taking action against that industry.

“Maine’s Climate Adaptation Costs: Holding Fossil Fuel Corporations Accountable,” an online presentation on Oct. 15 hosted by environmental groups, opened with Nellie Haldane of Blue Hill, a student at the University of Prince Edward Island, talking about her volunteer efforts to address rising sea levels in her hometown. Haldane showed slides of two fishing wharves in the community which were awash with water during a high tide and storm.

“By the late 1980s, the oil industry had a deep understanding of climate change.”

The town’s sea level rise task force on which she serves has estimated a cost of $60,000 for an initial assessment of vulnerable waterfronts. That figure is based on work done by nearby Stonington.

That modest, yet daunting cost of preparing for higher seas was an effective set-up for what followed.

“One of the most sobering facts” about Blue Hill’s plight, said Megan Matthews of the Center for Climate Integrity, “is that it shouldn’t be necessary. We are in the situation we’re in because of decades of climate inaction, rooted in denial and deception by the fossil fuel industry.”

Matthews highlighted three documents, from 1965, 1968, and 1982, which she said showed the fossil fuel industry knew and in fact was preparing for climate changes linked to carbon pollution.

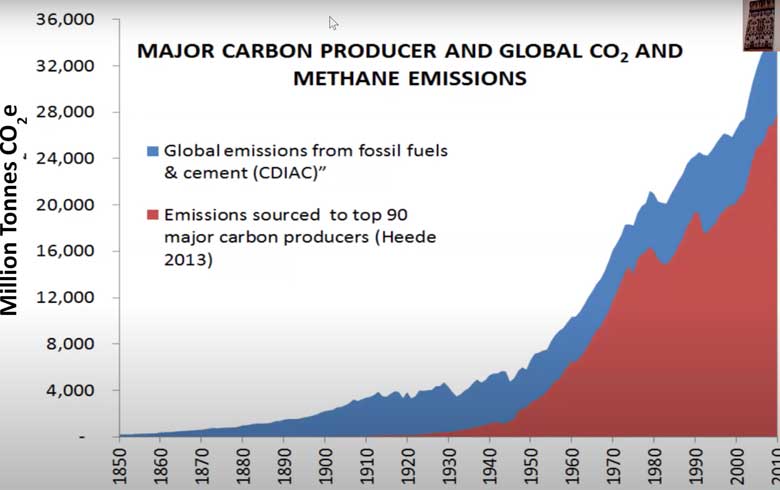

“The link between CO2 emissions and a warming climate was actually established back in the 19th century,” she continued, “but by the middle of the 20th century, the industry was starting to pay attention to the link between the burning of fossil fuels and increased atmospheric CO2, and the eventual warming was becoming more clear.”

Leaked documents from the 1965 annual meeting of the American Petroleum Institute, an industry advocate, asserted that carbon pollution would impact climate, Matthews said. A report prepared in 1968 by the Stanford Research Institute for the American Petroleum Institute concluded that carbon-linked warming could have a “severe environmental impact.”

A 1982 internal Exxon memo which Matthews showed asserted the same, that it “would have a measurable and significant impact on our climate.” And what might seem surprising today, she added, was that Exxon memos identified “an ethical duty” to address the impact.

Ed Garvey, an Exxon scientist working for the company from 1978 to 1982, has said: “The issue was not, were we going to have a problem. The issue was simply, how soon and how fast and how bad was it going to be. Not if.”

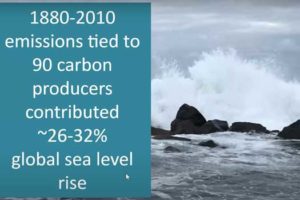

Matthews recounted more damning evidence from the early 1980s she said showed the fossil fuel industry knew what would come. “In addition to the effects of climate on agriculture,” one of its reports noted, “there are some potentially catastrophic events that must be considered,” especially if the Antarctic ice sheets began to melt.

In 1980, scientists hired by the American Petroleum Institute wrote that by 2067, “the world could expect to see a 5-degree temperature rise,” she said. Internal Exxon memos from 1982 describe the likely flooding of Washington D.C. and Florida.

“They started to prepare their own assets for this warming world,” Matthews said. Shell oil began raising its offshore oil rigs, for example. “By the late 1980s, the oil industry had a deep understanding of climate change.” But instead of warning the public, it lied, she said.

The pivot away from acknowledging the inevitable came in 1988. Matthews showed an ad paid for by Informed Citizens for the Environment, a coal industry advocate, from the 1990s which asked: “Who told you the earth was warming? Chicken Little?”

BIG OIL, BIG TOBACCO

“If it sounds like a massive, coordinated plan” to create uncertainty about the impacts of fossil fuels, she said, “I’m confident in confirming that it is, because we have the plan.” That plan borrowed from the tobacco industry playbook, she said.

And as with tobacco, climate activists want the fossil fuel industry to pay for the public impact of its products.

Corey Riday-White, a staff attorney with the Center for Climate Integrity, spoke about two dozen climate liability lawsuits currently working their way through the courts. Those include 18 municipalities, from New York to Honolulu, along with five states, Washington D.C., and the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations. The Center for Climate Integrity is not a litigant in these cases, Riday-White added.

Big oil knew, lied, “and now they should pay for it,” is the basis for the claims, he said. The claims rely on laws addressing nuisance, trespass, negligence, product liability, and consumer protection.

“Maine is facing very expensive climate adaptation costs in the very near future,” Riday-White said. “A massive gap will soon exist between those costs and the municipal and state budgets. At their core, these lawsuits are merely about who should make up that gap.”

The industry is working to move these state filings to federal court, where it will argue that the Clean Air Act is the arbiter of carbon emission, he said.