During a frigid February back in 2014, a group of fishermen from the UK came to Maine to give some advice to the fishing industry here on how it could better prepare for the emergence of offshore wind. Seven years later, those conversations out on wharves and in our conference room stick with us.

They shared stories of how the fishermen who engaged in the process were able to shift the orientation of the farm and allow traditional drift net fishing to still occur. They explained how they pushed for a requirement that the vessels engaged in the wind farm buy fuel from the fishermen and reflected on the benefits of coming together to speak with one voice in negotiations. They shared plenty of frustrations as well, but overall, we were struck by how they were able to shape the future of their coast.

As those who care deeply about the coast grapple with the latest round of discussions about offshore wind in the Gulf of Maine, these stories and others are on our minds. Since the development of Maine’s Ocean Energy Task Force in 2008, the Island Institute has worked to help the questions, priorities, and concerns of fishermen and fishing communities be heard in decisions about ocean use. As we move into a new set of work to support these conversations, here’s some of what we’re bringing with us from the past 13 years.

The use of ocean space can often be tied back to specific communities

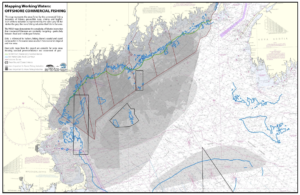

We know fishing boats leave from harbors, fish, and come back to their harbor. We have sat down with fishermen and asked them where their community fishes. They have shown us by marking spots on charts that outline these areas. When multiple interviews highlight a similar area, you can be relatively certain that specific part of the ocean has a connection back to that community. You can see the maps that emerged from this work here.

While it is hard to start with an area in the ocean and find every community that might fish there, it is possible to identify which harbors may have an outsized interest in a particular area.

Looking forward, the ability to link areas of the ocean to specific communities, and even specific working waterfronts, provides an important data point for understanding the potential impacts of a particular project. It also opens the door to conversations about minimizing those impacts or making investments that offset the impacts in some other way.

Mapping is the beginning of the conversation, not the end

Maps are great. Maps of fishing activity can help developers and decision makers understand who might be using a particular spot on the ocean. But maps of various ocean uses are only as good as the data that goes into them and how that data is visually interpreted and displayed.

From our work to assess and characterize fisheries data from around New England, we documented that the data sets available to agencies and developers generally do not tell the whole story. No matter how good the underlying data set is, it should be the starting point for conversations with fishermen. You can learn more about efforts to improve ocean planning processes here.

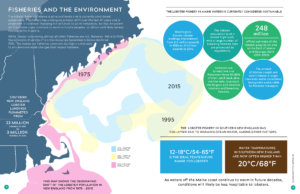

We know that things on the water are changing—and will keep changing

Lobsters are on the move. They’re occupying new bottom, and generally heading north or offshore. Unlike ferries or tankers, lobstermen and women must follow the catch and will need flexibility in where they fish in the future. If lobstermen are displaced due to new ocean uses, they not only lose where they fish but have to find new fishing grounds—others will suddenly have to accommodate newcomers in their fishing areas.

Climate change will continue to impact both where lobsters are located and how the fishery operates, and the lobster fishery needs the flexibility to respond to long-term trends as well as short-term annual variability. To go deeper on this issue, check out our 2016 “Lobster and Ocean Planning” report here.

There’s a need to go deep when trying to find solutions

The ability to engage in the offshore wind development process requires you to do your homework. In the U.S., the development of a project can take a decade or more and is filled with complicated processes and technical language. To fully engage is time-consuming and even emotionally distracting, particularly when it’s not your day job.

Yet if you travel to one of the island communities in New England that are proximate to proposed offshore wind projects, we can guarantee that you’ll find that most residents have become well-versed in these processes and can even cite enabling legislation and the specifics of regulatory review. They may be for, against, or agnostic to a project, but it is clear they’ve done their homework and invested in ways for their communities to engage in the process.

Check out this short video of the work that the community of Block Island, Rhode Island, neighbors of the nation’s first operational offshore wind project, did to engage in that project’s development process.

Communities can find synergies with projects

Community Benefit Agreements (CBAs) are standard components of most utility-scale energy projects, including offshore wind. In Maine, they were even required by statute for land-based wind projects, as well as the offshore wind project off Monhegan. Communities can influence these agreements, particularly if they have done their homework on a project, organized the community to speak with one voice, and are willing to engage a developer in constructive dialogue.

Since 2014, the Island Institute, through our Islanded Grid Resource Center initiative, has researched models for community benefit in the renewable energy industry in Maine and globally and connected communities from these places to islands in New England. In doing so, community leaders have shared their experiences working with developers and the strategies that helped to increase local capacity to negotiate. These stories were highlighted earlier this year through a University of Rhode Island-hosted webinar on negotiating partnerships between communities and the offshore wind industry.

Looking to the future

Offshore wind is no longer a matter of “if,” but of “how” it will impact the fishery and the communities that depend on the ocean for their way of life. As our friends from the UK and on southern New England islands have shared with us, it can be a time consuming and frustrating process, but learning about a project can be a two-way street that values local knowledge in addition to technical and regulatory information. By slowing down and creating the opportunity for local insights to surface, we’re hopeful that more creative and beneficial solutions can be unlocked.

Learn more about how we’re engaging on this important issue. Visit our Climate & Energy page and read our full statement here.