A Distinct Alien Race: The Untold Story of Franco-Americans

By David Vermette (2018)

Growing up in the Midcoast, the only thing I knew about French-Canadians was what I learned from my dad. He said the stereotype was of the “dumb Frenchman” who usually took shop classes in high school and went directly to work in the mills after graduation. The other kids in Augusta called them “frogs.”

What struck me most about these stories is that my dad described them like they were another race of people. He told tales of going up to Quebec City after high school to party with his friends in the late 1950s and how “those French-Canadian girls really went wild for us white guys,” like he was talking about military adventures in Asia on R&R.

When Paul LePage was first elected governor, my father remarked: “Finally they elected one of their own and he goes on to prove every single ugly stereotype about them.”

They suffered sectarian violence at the hands of Protestant zealots and were targets of the Maine Ku Klux Klan…

I told these stories to some Franco-American colleagues in the Maine Legislature with some amusement because it seemed so ridiculous that a white person could be racist against other white people. But my friends reacted with visible anger. They weren’t that much younger than my father’s generation and had personally experienced this kind of abuse growing up.

In his 2018 book A Distinct Alien Race: The Untold Story of Franco-Americans, David Vermette tells the story of the 19th century New England textile barons who created what became the modern corporation, building their fortunes on the backs of a French-Canadian working class. Described by one Massachusetts labor official as “the Chinese of the eastern states,” the mere presence of French-Canadian immigrants fueled anti-Catholic conspiracies that claimed they were part of a papist plot to establish a Catholic theocracy in the region.

In his 2018 book A Distinct Alien Race: The Untold Story of Franco-Americans, David Vermette tells the story of the 19th century New England textile barons who created what became the modern corporation, building their fortunes on the backs of a French-Canadian working class. Described by one Massachusetts labor official as “the Chinese of the eastern states,” the mere presence of French-Canadian immigrants fueled anti-Catholic conspiracies that claimed they were part of a papist plot to establish a Catholic theocracy in the region.

They suffered sectarian violence at the hands of Protestant zealots in the 19th century and were targets of the Maine Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. Academics promoted since-discredited eugenics theories that French-Canadians were biologically inferior to the dominant Anglo-Saxon Protestant race.

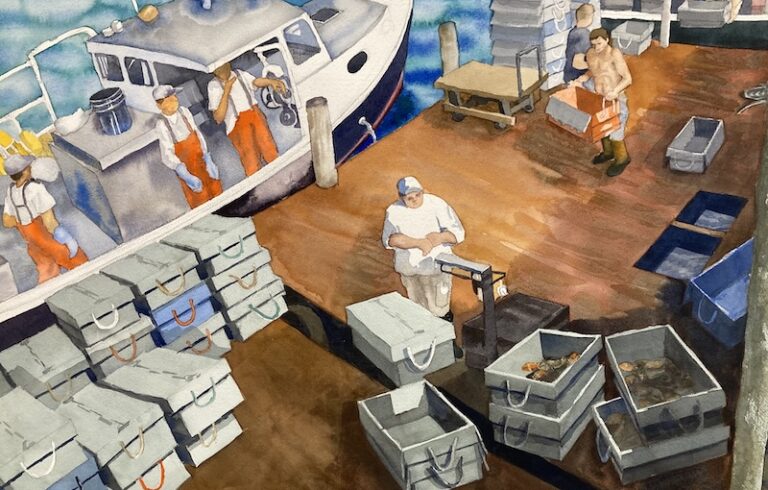

But to the wealthy factory owners in Boston, the new arrivals were a very profitable resource. Vermette describes the first New England mills as a “utopian industrial experiment” aimed at creating an alternative to the deplorable conditions in the factories of England. Even Charles Dickens was impressed with the treatment of young Yankee female operatives in Lowell, Massachusetts in the 1840s.

“They were healthy in appearance, many of them remarkably so, and had the manners and deportment of young women: not of degraded brutes of burden,” he wrote.

But there was nothing utopian about toiling in a noisy textile mill from dawn until dusk for low pay and soon the young Yankee women were striking for better pay and working conditions.

By the Gilded Age, mill owners found that a poverty-stricken immigrant workforce was much easier to control. Companies began warehousing the new workers in cramped rooms in shoddily built tenements. Plagues of dysentery and typhoid from water contaminated with sewage and toxic chemicals claimed the lives of numerous young French children—their graves still dotting the cemeteries in mill towns across Maine. Managers cared little about workplace safety and countless limbs were lost in accidents due to their neglect.

The public would consider these conditions to be unacceptable for good Anglo Protestant Yankee women, but since it was only papist French peasants, the mill owners no longer needed to recognize the humanity of their workers. As one manager said, “I regard my work people just as I regard my machinery. So long as they can do my work for what I choose to pay them, I keep them, getting out of them all I can.”

Eventually conditions improved as workers unionized, but factories were outsourced, first to the South and then overseas where workers of color could be more easily exploited. Later generations of French-Canadians assimilated and became simply “white” in the eyes of American society.

Darker skin pigmentation continues to be what identifies people who belong to a lower caste. Sadly, these days many Franco-Americans show the same kind of contempt toward African immigrants that the Yankees had for their ancestors.

As history shows, American society will accept the brutal exploitation of other humans for profit if we view them as inferior. Unfortunately, racism continues to be the biggest barrier to enacting policies that uplift the working poor.

Andy O’Brien is a freelance writer, labor activist, and former managing editor of the Rockland Free Press.