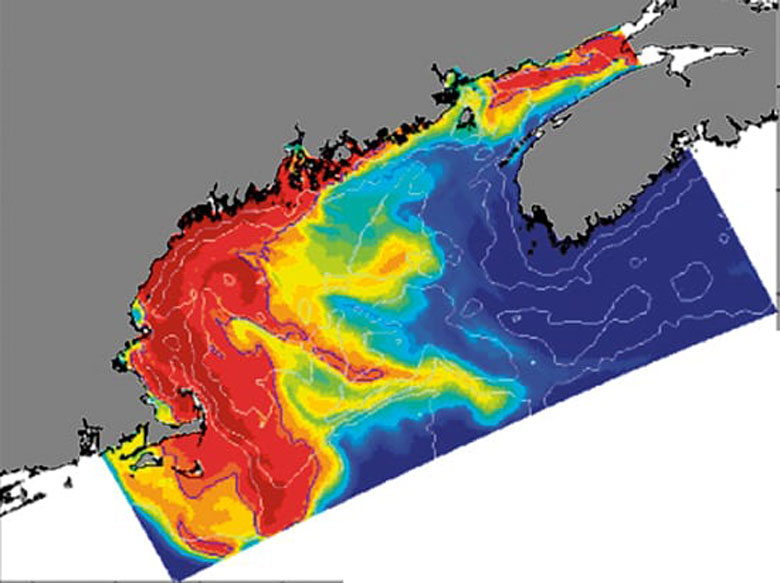

Fishermen love their coffee, but they don’t want the ocean to look like it! Last summer, that is just what the ocean looked like across the Gulf of Maine, from Penobscot Bay to Martha’s Vineyard.

The brown water was the result of a massive bloom of microscopic algae (otherwise known as phytoplankton). As this bloom grew denser over the course of the summer, it reduced sunlight penetration in the water column which led to the dying of these sunlight-dependent algae, which in turn is gobbled up by bacteria.

This resulting bacteria bloom consumes oxygen in the water and gives off carbon dioxide which can, when blooms are big enough, induce dangerously low oxygen levels in the water, known as hypoxia.

In recent years, Cape Cod lobstermen have seen dead and declining lobsters over time because of hypoxia.

Hypoxic waters can create dead zones, where die-offs of fish, shellfish, and aquatic plants can occur. In 1999, 75% of the lobster in Long Island Sound disappeared; a contributing factor was hypoxia.

In recent years, Cape Cod lobstermen have seen dead and declining lobsters over time because of hypoxia and they certainly saw the negative impact of last summer’s bloom.

Just as concerns about hypoxic waters were mounting farther north, the seasonal changes and storms in the Gulf of Maine reduced favorable growth conditions and the bloom subsided—for now. It is interesting to note that researchers are finding algae blooms increasingly hard to predict, with many surprise events, including the presence of non-native species.

But before you start hating phytoplankton, I must point out that it is, of course, not so simple. The abundant marine life in the Gulf of Maine is built on a foundation of critical seasonal (mostly spring, sometimes fall) phytoplankton blooms.

However, as we all know—perhaps ponder your last holiday meal—there are times when we experience too much of a good thing.

Harmful algae blooms (HABs) are blooms of microscopic organisms in fresh or salt water that produce toxins and/or hypoxia-inducing dense blooms. While all HABs have the potential to induce hypoxia, toxic HABs are also notorious for shellfish poisoning, respiratory irritations in humans, and many negative health impacts for fish, marine mammals, and birds.

HABs are often induced by sunlight, salinity changes, warm water temperatures, ocean currents, and especially the input of nutrients running into the ocean during rainstorms. Climate change is increasing water temperature and causing more extreme rainfall events in Maine and thus, HABs are expected to increase over time.

The tools to combat algal blooms are pretty good right now, but as conditions that support blooms increase with climate change, we need to increase ocean monitoring and reduce nutrient pollution.

As these blooms are becoming more common, federal and state agencies, research organizations, and fishermen have joined together across the Gulf of Maine to track water conditions. This tracking can guide research and action from nutrient reduction to moving lobster traps.

A major monitoring effort is underway through the Integrated Ocean Observing System, a partnership among federal and state agencies, universities, and non-profit organizations which serves as the nation’s “eyes on the ocean.” The system operates a variety of ocean observation technology across the Gulf, provides real-time data on water conditions, tracking potential and occurring blooms.

Dr. Jake Kritzer and Jackie Motyka from the observing system’s northeast office stated last fall that while the identification and monitoring of last summer’s bloom was effective and showed the value of the system, it also illuminated some gaps, like offshore monitoring in the northern Gulf of Maine. With proper funding and expanded partnerships, this gap can be closed.

Nutrients, especially nitrogen and phosphorus, originating from land-based human activities gets washed by rainstorms into rivers, lakes, and the ocean triggering and feeding algae blooms (and increasing ocean acidification). Cleaning up waste, reducing storm run-off from streets, yards, wood processing, and agricultural lands can significantly reduce the potential of algae blooms. Maine’s best management practices for regulating run-off is identified in the Maine Climate Action plan for updating and improvements.

Finally, certain marine ecosystems like oyster beds and eelgrass naturally filter nutrients out of the water. Restoring and promoting natural systems is a win-win for a healthy Gulf of Maine to support us, our economy, and nature itself.

Jennifer Seavey is chief programs officer with Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. She oversees strategy and supports work in climate resilience, the marine economy, and sustainable community development. She may be contacted at jseavey@islandinstitute.org.