The town of Islesboro will be moving ahead with a two-pronged approach to maintain a vital road connection between the island’s northern and southern communities after four 100-year storms damaged the roadway over the last 12 months.

SEE A SHORT VIDEO ABOUT THE WORK:

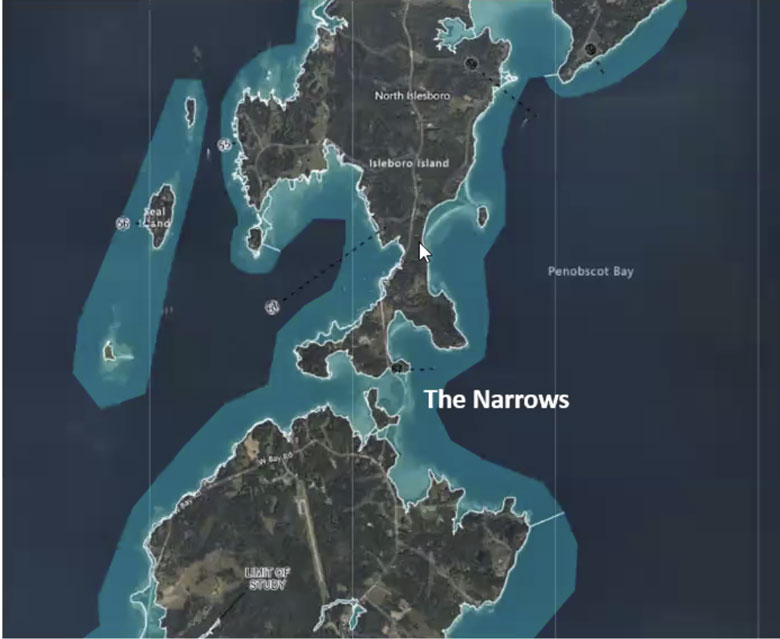

The Main Road crossing the Narrows—a low-lying stretch of land at the midisland’s belt—was briefly severed by the Jan. 10 winter storm. Its protective riprap seawall was overtopped by high tides and wave action, cutting off emergency services, ferry access, and other down-island services to residents living up-island.

While the island’s road crew and contractors patched the roadway back together once the tide receded, the following January 13 storm undid much of their work.

“With the current storms we’re getting, we need to do something as quickly as possible.”

“The road was impassable not just at the height of the storm, but for at least a half-day until local contractors could come in,” said select board chairwoman Shey Conover. “Those January storms were a huge wake-up call. The destruction we saw and experienced bolded, underlined, and accelerated our plans to develop a more resilient solution.”

“It just ripped the road right out,” Town Manager Janet Anderson agreed. “If they can’t cross it—can’t get a firetruck or ambulance through—a lot of people are worried about that.”

Now armed with a $75,000 Maine Infrastructure Adaptation Fund grant awarded to the town on Aug. 8, Islesboro officials hope to advance engineering plans that call for a slightly higher roadway in the near-term (phase one) and a bridge in the next decade (phase two).

While the recent winter storms highlighted the fragility of the road connection across the Narrows, Islesboro residents have long fretted about the Main Road’s vulnerability to the elements. Nearly 10 years ago, in 2015, the town won its first grant to study the flood risks at the Narrows and Grindle Point, another vulnerable area on the island.

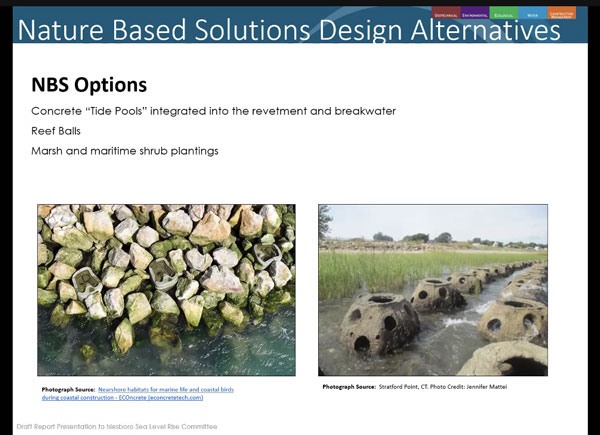

A subsequent 2017 report recommended adaptions such as hardened seawalls, nature-based features such as marsh creation, and warning systems. It also led to the formation of the town’s Sea Level Rise Committee (SLRC).

But it wasn’t until the fall of 2022, when Islesboro enrolled in Maine’s Community Resilience Partnership Program, that infrastructure planning accelerated. Joining the program garnered a $50,000 Community Action Grant from Maine’s Community Resilience Partnership program, which in turn enabled the town to the hire Shri Verrill of Sunrise Ecologic in 2023. An ecological restoration and watershed protection specialist, Verrill was charged with advancing the Narrows adaptation plan.

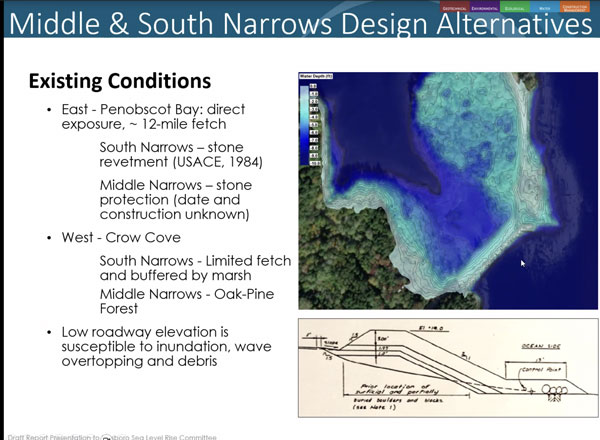

In early 2024, Verrill and the SLRC selected GZA Geotechnical Engineering to move the plan into the design phase. After six months of analysis funded by a new Coastal Communities Grant from the state, GZA prepared about a half-dozen alternatives for the town’s consideration. Each scenario was designed in three sections: north, middle, and south Narrows.

“All of the short-term, phase one alternatives were consistent about raising the road and rebuilding the stone revetment in the south and middle sections of the Narrows,” Verrill said.

But they differed about how high the revetment should be raised, how wide, and what materials should be used to provide barriers to reduce the force of wave actions during storms occurring at high tide. One proposal, for example, called for manmade reef balls to be anchored in the intertidal area east of the roadway, at the south and middle Narrows, that could lead to the development of new intertidal habitats that could help protect the shoreline.

Based on community feedback, Conover said, the SLRC recommended—and the select board agreed to—an alternative Verrill dubbed “short, wide and with a berm.” It would raise the road 2 feet immediately, maintain a planted slope of protective vegetation, and rebuild the stone revetments on the east side of the road.

“Those have been protecting the road for 40 years, but the January storms showed us that they are failing,” Conover said. “Stones are smaller, breaking up, and in the storms are becoming projectiles.”

Conover hopes it could be fully completed by 2027.

Verrill said that while the planning process may seem long to outsiders, it’s been exemplary in terms of involving the public in decision-making.

“It’s important that people are able to see the vision,” she said, explaining the value of the series of presentations and public input meetings leading up to the adoption of the current two-part plan. “They need to feel it in their gut and provide their consent.”

NEXT STEPS

One question that came up frequently among community members was if the 2-foot increase was sufficient. After all, the Maine Climate Council has recommended managing for at least 1.5 feet of sea level rise by 2050 and preparing for a possible rise of up to 3 feet over that time.

Conover, who also chairs the Sea Level Rise Committee, said any height increase would require an increase in the roadway’s width, which could then impact the salt marsh on the road’s west side. Minimizing potential damage to the marsh was one of the values many community members expressed in the meetings.

“If the road goes up, it has to go wider,” Conover said. “So we felt that the 2-foot increase—which is consistent with state projections for 2050—was the most likely to receive permits.”

Conover also said some townspeople wondered if it didn’t make more sense to skip right to a bridge. But she argued that the engineering, permitting, and funding processes required would push that solution back to 2031—and probably beyond. Up-island residents can’t wait that long for a resilient, dependable road.

“With the current storms we’re getting, we need to do something as quickly as possible,” Conover said.

“If we continue to get four 100-year storms within a 12-month period, it will be a very taxing experience until the bridge is built,” Verrill agreed.

As for phase two—the bridge across the Narrows—Verrill said most of the planning and design remains incomplete. At this point, engineers envision the bridge being built from the southern end of the Narrows, and west of the current roadway. There are also discussions about a bridge option for the north Narrows, which also would likely be placed west of the existing roadway.

“There are conceptual drawings, but not designs, for what we are calling phase two,” she said. While it would guard against the possibility of relative sea level rise of 3.9 feet by 2100, the bridge—or bridges—would be built on pilings that would encroach on the salt marsh.

“There’s no way around that” said Verrill, who is a salt marsh ecologist by training. “But those impacts will be minimized at every opportunity.”

As for Anderson, the town manager, phase two remains little more than a possibility unless federal construction grants can be secured.

“Townspeople are committed to this—until they see a price tag,” she observed. “If they’re asked to come up with $20 million to build it, I don’t think that would fly.”