Unleashed and Other Poems

Moon Pie Press, 68 pages

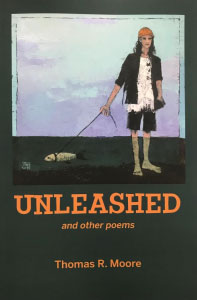

The title of this book, Unleashed and Other Poems, and its cover, which features a painting by Sheep Jones of a figure walking a fish on a leash, reflect a new direction for Tom Moore, former Belfast poet laureate: an unplugged sense of humor. At the same time Moore adventures into metamorphosis via a curious creature kinship that enlivens several poems.

The title poem, prompted by the Jones painting, finds the poet swimming alongside a bass after removing its leash. The matter-of-fact quality of the account of exploring Belfast harbor and beyond—“The water’s a bit/cooler out here, clearer too”—brings to mind the synthesis of the real and the surreal found in the poetry of Russell Edson and Gregory Orr.

In “A Plague of Grackles” Moore considers a group of these birds descending on seeds he has scattered.

“They must have texted/all their cousins because by noon there are/hundreds,” he writes, before describing a kind of Hitchcockian moment when the birds attack him. He ends up joining the flock, his “new comrades,” and appreciating their “raucous puns.”

Several poems are out-and-out funny.

“Nothing Sucks Like an Electrolux” pays tribute to a ’67 vacuum cleaner, transforming it into a “bad-ass” babe, “leggy and ready to roll.”

A few poems complain. “Cacophony in B Sharp Major for Blades and Blowers” takes aim at neighborhood noisemakers.

In “Dirigo, Olfacio, Mingo” (Latin for “I lead, I sniff, I pee”), a dog samples scents on an early morning walk. “Light bodied./Almost floral. Must be Olive, the eye doctor’s/Cavalier King Charles.”

A few poems complain. “Cacophony in B Sharp Major for Blades and Blowers” takes aim at neighborhood noisemakers. A final rhyming couplet suggests a solution: “We cannot hear each other when we eat,/please jump into a slab of fresh concrete.”

A poet of carpentry and tools—previous books include Chet Sawing, The Bolt-Cutters, and Saving Nails—Moore once again pays tribute to builders. In “Truck Lust” he and his brother play with the trucks their father, a carpenter, made, “as big as breadboxes or couch cushions.”

Here’s the second section:

My father had pages of distance and pages

of anger, but the wooden trucks smiled his

warmth—red paint, hinged dumps, cabs.

Moore also broaches intimations of mortality, at times tongue in cheek, at others, not so. In “Going Back: Getting Lost in Heaven” he moves from describing a house he built—“I cut studs and toe-nailed them”—to the “terrible signage” he finds in heaven. Disgusted with the “bastard at the gate,” the poet now lives for “sunrise, that moment when red slashes the underbelly/of the horizon, and all I have left is words.”

Those words are consistently deployed with consummate craft. In the final poem, “December: Belfast Waterfront,” Moore offers a tour of the harbor. An inventory of vessels includes “Abide, ketch rigged, one hundred/thirty feet of opulence” and two Fournier tugs standing by “to nudge tankers into Searsport.”

The poet knows and cherishes this world and, lucky us, shares it.

Carl Little is the author, with his brother David, of Art of Penobscot Bay (Islandport Press).