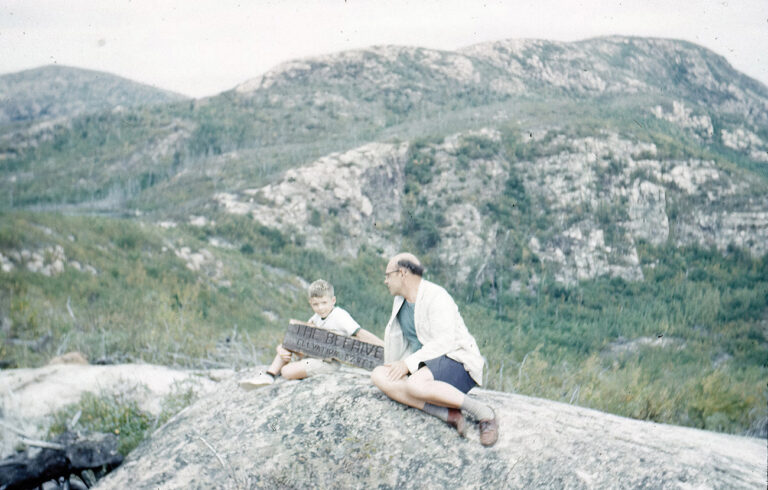

Photos by Barry Fitzsimmons

A career in journalism means being an observer, not a player. It means not taking sides, even when it comes to an endeavor as worthy as eldercare for a small island community.

Susan Stranahan says that when she left daily journalism and moved to Chebeague Island in 2008, she welcomed the opportunity to set aside being an observer and give back to her adopted home. And she has worked for the Island Commons, an assisted living facility which opened in 1999, with the same gusto that made her a successful reporter.

As is the case with many, Stranahan’s journey to the Casco Bay island was laced with serendipity. In 1969, her parents were on a winter getaway, contemplating a family summer vacation. He wanted to play golf, and she wanted to go to Maine—ideally an island.

A man sitting at an adjacent table overheard the conversation. He happened to be the director of Maine’s tourism office, and suggested Chebeague, which of course has a shorefront golf course and plenty of charm. The Stranahans rented a cottage that summer, were welcomed to the island, and eventually bought a historic home where they summered for many years.

“I started coming to visit my parents, and I loved it,” Stranahan says. In 2002 she bought a century-old house on the water, and in 2008 became a full-time resident. She continued to work as a freelance journalist, but now also had the opportunity to volunteer. And, she discovered, volunteers were in high demand.

Stranahan found her career path early in life, thanks to her father.

“My dad wanted me to be a newspaper reporter,” she remembers. It was a career he once had dreamed of, ultimately becoming a lawyer and then a trial judge.

“He got me a job at age 15 at a daily newspaper. The minute I walked into that office, I knew this was what I wanted to do.”

Given the size of their small county in western Pennsylvania, there were occasional conflicts during the six summers she worked at the paper. If the court calendar was full, and both judges were presiding at trials, her boss took one trial and she was assigned to cover her father’s courtroom proceedings, a conflict no modern-day editor would condone.

“Dad kept a close eye on me, once even asking me to move to the opposite side of the courtroom when one of the defendants got a bit too chummy,” she laughed.

Her father’s career had much to offer a budding reporter, Stranahan says. His professional values—to listen and be fair—were essential in her work.

“Everybody has a great story to tell” was another maxim he shared. But mostly, he supported her interest in the work.

“He just loved that I was a reporter,” she says. “And that I eventually was also to share my parents’ love for Chebeague Island.”

Stranahan at her desk in her Chebeague Island home.

Stranahan attended The College of Wooster in central Ohio, and after graduation, she landed a job at the Cleveland Plain Dealer. Four years later, she was hired by the Philadelphia Inquirer, where she worked as a reporter and editorial writer from 1972 to 2000.

Her beats included the courts and the environment, a focus area for which the executive editor wasn’t initially enthusiastic. “He thought environmentalism was a trend, a fad,” she remembers. That view quickly changed.

Pennsylvania was home to the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant which began operating in 1974. In 1978, Stranahan toured the plant for a story and so knew the basics of how it operated. Then, in March 1979, a nightmare scenario began unfolding.

Early one morning, reporters at the Inquirer’s Harrisburg bureau began hearing police and other emergency responder alerts about an event at the plant, a few miles south of the state capitol. They notified the city editor about what seemed to be problems at TMI. Stranahan happened to be in the nearly empty newsroom when the call landed.

“Based on my one visit, I was the ‘expert,’” she remembers. By mid-afternoon she had become the paper’s point person in the Philadelphia office, ultimately fielding updates from about 40 reporters and photographers covering the developing story and rewriting them into rapidly changing news coverage. What had begun as a local story soon became a global one, with experts warning of a meltdown and the potential spread of radiation over much of central Pennsylvania.

The paper was printing four editions in those days which meant deadlines fell at 6 p.m., 10 p.m., midnight, and 2:30 a.m. Stranahan was anchored to the desk and phone through them all.

“It was really scary,” she recalls. “There was a real fear that the place was going to explode. It was up to us to keep the public informed.”

The Inquirer won a Pulitzer Prize for its coverage of the crisis.

She readily agrees that her career followed the arc of a golden age of newspapers. “The Inquirer was a fabulous place to be, at a fabulous time to be a reporter.” Long investigative projects were encouraged. Great editing was prized.

And there were plenty of fun assignments. She remembers hearing about Canadian wildlife officials airlifting polar bears out of a dump in Manitoba and pitched it to her editor. “Oh, yeah!” was the answer. “Take a photographer!”

After leaving the Inquirer, she taught at the University of Pennsylvania and freelanced, eventually heading to Chebeague to continue working. In 2011, she was asked by the Union of Concerned Scientists to help write Fukushima: The Story of a Nuclear Disaster about the impacts a tsunami had on a power plant in Japan. That wasn’t her first book. She wrote Susquehanna, River of Dreams, about the watershed that feeds the Chesapeake Bay, published in 1993.

“There’s nothing more joyous than writing,” she said.

Stranahan, center, at the Island Commons eldercare facility with Amy Rich, administrator, at left, and Nancy Olney, community outreach manager at right inside the facility.

But Stranahan is more interested in talking about her current efforts than in reciting her past successes.

“I grew up in a little town and volunteerism was always a part of your existence,” she said. That ethic is especially important in the small Chebeague Island community. “You owe it to the community to get involved.”

Soon after arriving on the island, she was asked to join the board of the Island Commons, Chebeague’s elderly housing facility, which is licensed for seven residents. It’s been at capacity for several years.

“I was really pleased to be asked,” Stranahan said, despite having no eldercare or even nonprofit experience. It was an opportunity to get to know her new community and to give back, she said.

In 2010 Stranahan joined the board of the Chebeague Transportation Company (CTC) and remains active as a director of the ferry company. She helped CTC win nonprofit status, oversaw the hiring of a full-time general manager, and worked with the board and staff to devise safety protocols throughout the COVID epidemic.

“CTC is Chebeague’s lifeline,” she said.

“Among life-long islanders, there’s a respect for volunteers,” she said, reflecting on her new role. “What keeps the island running 365 days a year is the commitment of its volunteers. It’s something summer people often don’t appreciate fully.”

The Island Commons meets another critical need on Chebeague. About a quarter of year-round residents are over 70, and many have spent their entire lives on the island.

“They are the ones who should be able to live out the rest of their lives on the island with their family,” she says of residents. “They have cooked for community suppers, risen early to start the furnace at church, and established the ferry company. Now they need some assistance,” she said.

“They’d like to stay at home,” but the Commons offers an alternative. The nonprofit also has begun offering in-home care service for the elderly on Chebeague and nearby communities.

The Commons employs 23 full- and part-time staff, which includes a case manager, administrator, outreach coordinator, and caregivers. Stranahan is president of the seven-member board, and she writes grants, appeal letters, and speaks on behalf of the nonprofit.

One of her proudest accomplishments to date is the small resale shop opened a few years ago in an empty building at the Commons. Today, the Red Studio is a popular summer gathering spot on the island, selling donated inventory with all proceeds going to the Commons.

“I never thought I’d find joy refinishing furniture,” she says with a laugh, but it’s another part of what drives Stranahan. “I can help make this place work. It’s nice to be able to give back.”

Tom Groening is editor of Island Journal and The Working Waterfront.