Illustrations by Ted Walsh

Sailors once thought sea gods ruled. Poseidon. Neptune. Aegir. Ran. Tangaroa. Now they know the sea has moods. Calm. Peaceful. Troubled. Angry. Mean. But the open ocean shows no sign of caring. It frolics and rages as it chooses, indifferent to fears and pleasures aboard, unconcerned with the vessel, whether of wood or steel or fiberglass, whether beautifully designed with a pedigree or merely riveted and welded for efficiency. Neither polish nor rust affects the force of wind, the height of waves, and the absence of mercy.

The sloop had a pedigree. It was gliding down the long Atlantic swells in a purple dusk. The slender hull, as graceful as a fin, hissed through the water. A classic Pilot 35, built lovingly by Hinckley, treasured by everyone who ever owned one, including their friend’s father, who had asked for a favor. What a favor! The brothers and their friend were helping his father sail northeast from Plymouth to Bar Harbor. The course put the prevailing southwest summer wind at their backs. The swells came from behind. The boat was lifted and lowered by a following sea.

In the early day, gulls that like to hover and prowl around the sand bars and rockweed still wheeled alongside the boat, and terns screeched and dove in frenzied hunts for silver flashes of fish. The boat, named Spray, had not yet sailed far enough offshore to shed the civilization of the coast.

The brothers would take the watch from midnight. In the brief darkness of June they would be lucky enough to witness the enlightenment, that slow dawn revelation of the watery, heaving Earth. For that, it was a prized watch, worth the hours of blind blackness before the expansive spirit gradually opened their seeing.

Nick was always taller, always would be taller, Barry supposed. And firmer in the chest. Muscles bulged when he wore a T-shirt, because he worked out so much down in the damp basement, barbells wrenched from the concrete floor and curling up, then down, sweat staining his shirt despite the coolness down there, adding weighted discs at the end of each stainless bar so that Barry could only struggle to lift one of them, then quickly put it down.

“Don’t strain yourself, kid. It’ll come when you get bigger.”

“I am bigger, and it never comes.”

“I mean really bigger. You’re 14. I’m 20. Besides, I’ve been to ‘Nam. That’s a place where you get bigger really fast. Too fast.” Then his voice trailed off, as every time he’d mention ‘Nam, and his gaze would retreat from seeing something right in front of him to watching some inner thing, it seemed, something in a dream. A bad dream, Barry thought.

“What was it like?” Barry asked occasionally. Nick never really said.

“Hot. Rainy. Lots of bugs. Lots of hot girls in town, near the base.”

“I mean the war.”

“Fuck the war.”

“What was it like? Did you kill anybody?”

“You don’t want to know.”

That’s the way he ended every conversation: You don’t want to know.

Nick seemed different when he came back. The difference seemed too misshapen to measure. Nick didn’t talk as much. He didn’t laugh as much. He didn’t pal around with Barry as much, the way they’d done when they’d pegged a baseball back and forth harder and harder to see who’d give up first, or climb the gnarled apple tree over at Mr. Page’s to see who’d get higher. Or made sling shots together out of perfect forked branches with the bark shaved off and thick rubber bands and leather pouches Nick got from somewhere and see who could fire a stone precisely enough to punch out a window in the abandoned fish plant with a satisfying jangle.

“Don’t tell Mom,” Nick would say, so Barry wouldn’t. But he wanted to—to brag and confess all at once. “Don’t tell Mom and Dad,” Nick said when they climbed around the construction debris down the block and took home a stray box of nails. “Don’t tell.” It made Barry’s neck feel hot.

Nick spent more time alone in his room now, and out back just sitting, looking at the grass and the woods. He sometimes brushed Barry away when he came near, as if solitude were a fortress. Often Nick started, jumped, and ducked when he heard a sound behind him, even just a squirrel rattling in a branch.

He also seemed stuck back in time, as if Barry were still the puny little boy he left behind when he got called up. That was fine when Barry used to need Nick to scowl and grumble at Leon the bully and his bunch who tossed stones at him as he rode his bike, or chanted that he ran like a girl. Nick would saunter over to them and lean down as if he were going to grind them into the dirt and say something like, “You got a problem?” And they would know exactly what he meant. Barry would be home free for the next week or so.

But, hell, he was now 14, “a young man,” his father had said on his birthday. Nick still called him “kid,” which used to mean he loved him and protected him and now meant something else. Barry wasn’t quite sure what, something less fond, more diminishing.

So Barry tried to get on an equal footing and make “young man” talk, if not about the long yesterday of brotherhood and the near yesterday of war, then about today and the near tomorrow.

“What are you going to do after the summer?” he asked Nick. They were sitting out back, where the summer green should have felt soothing. No reply, just an irritated sigh. “Thinking about college? A job?”

“What the fuck do you care?”

Barry’s face burned, like after a slap. He didn’t say anything for long seconds, but then: “Because I care about you, asshole. You’re my brother. I’m interested.”

“Oh, yeah, sorry, kid, sure you are. Well, I’m interested myself, but I don’t have an answer. When I do, you’ll be the first to know.” Then he laughed, but all by himself in a hollow way that people do when they don’t have anything to laugh about.

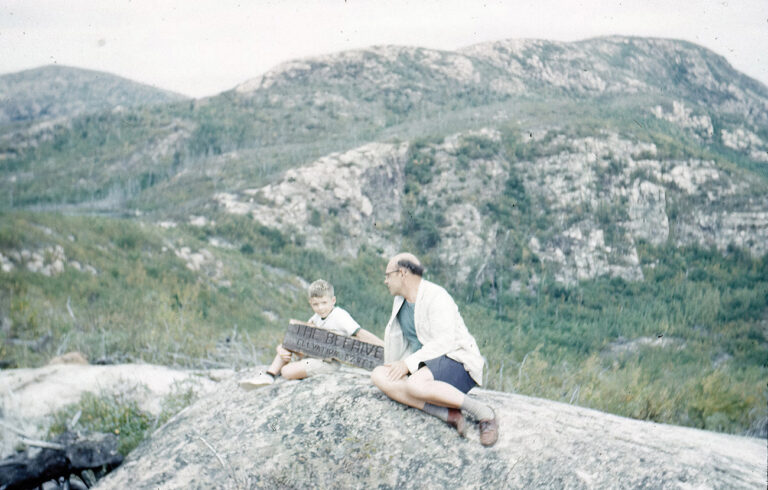

“I’m going to Stonewood again for six weeks,” said Barry. “It’ll be my fifth year. The sailing’s great, both on the lake and from the harbor. We had a super racing team last year.” Nick said nothing. “Too bad Mom and Dad didn’t find that place when you were young enough to go. You’d have loved it.”

“I had my own sailing camp with the guys around here. They taught me the ropes. Then I taught you a thing or two. I figure someday you might make a good sailor.”

“I’m a good sailor now.”

Nick gave a sharp cluck with his tongue, like a key locking. “Ha. You know the law of the sea? Overconfidence can be fatal.”

“Speaking of fatal, did you lose any buddies over there?”

“You don’t want to know.”

Barry liked the first light when the deep dark was diluted just enough to allow a peek at the coming day. When crystal clarity was promised by the dawn, he got up and waited impatiently for Nick to rise. He’d dropped one little-boy habit—of jumping on Nick’s bed to shake him awake and tease him about being late and wrestling around in cheers of abandon. He knew now he’d get grouched at, maybe even punched on the arm. So he ate cold cereal by himself, watched the brightening through the window, then assaulted Nick as soon as he walked to the bathroom.

“What are you doing today? Maybe we can get Billy and his father and take their boat out for a sail. We’re leaving in ten days, better have a shakedown.”

“Don’t feel like it,” Nick grumped.

“There’s a nice wind coming up this afternoon, ten to 15 southwest.”

“I told you I don’t feel like it.”

“You’re not even awake enough to know what you feel. Dad thinks we need a refresher before heading out.”

“You might need a refresher. I know what I’m doing. Once you know it, you know it. Like riding a bike.”

“Overconfidence,” Barry whispered, then dodged a punch, not a playful one. “Nick, it’s the Gulf of Maine. Offshore. That’s different from bays and coves. We need to learn their boat better.”

“Speak for yourself.” Nick’s back looked iron stiff as he stalked off to his room.

So Barry walked firmly into the rising morning. He took the narrow blacktop road from the house along the gentle slope of dune grass lining the beach. He removed his flip-flops and crossed onto the sand and stopped. “There are two golden hours,” he said aloud. Talking was his habit in aloneness. At times, when he scolded or wondered or coached himself along, or just thought randomly, he mumbled. At other times, sure that nobody was close enough to hear, he orated and declared. Now he lectured the spiraling gulls and whatever sand crabs or jellyfish or other creatures he could not see. “Two golden hours every sunny day, one after dawn, the other before dusk, and here it is. Look at the tint of every surface. Look at the sparkles on the water. A fine day. A fine day for sailing.” Then he kicked a small stone in anger and stomped on an empty crab shell. “The breeze will come up after lunch,” he announced. “Stupid Nick.”

He sat down on the sand to watch the water’s light gain the complicated colors of the morning. “I wish we could be like we were before. No, I wish we could be like we should be now.” He found a thin, flat stone, walked to the lip of the bay, and skidded it sidearm so it skipped 13 times. “Thirteen! All right!” Would Nick believe him?

Barry stood, balanced his stride carefully along the water’s edge, and imagined the lip between sand and sea as the line between now and someday. “Now and someday,” he said aloud. He turned inland through the tall grass and back to the black-top road, ambling on until masts rose from the marina. Since he could remember, and maybe from before that, he had loved to stroll on docks among boats, breathing in the pungent smell of varnish and the sweetness of aging painted wood. The docks stuck out like fingers from a long wharf, harboring sleek power cruisers and dumpy skiffs, sloppy old sailboats and pristine yachts with varnished teak and not a smudge on hulls or decks.

At the final dock, he continued until he could see the dark blue prow, and he imagined her as the afternoon wind would come up, bobbing in her slip, straining restlessly against her lines. He stood by her, inspecting her fore and aft, from the bow pulpit down the foc’s’l past the life raft in the white canister bolted to the deck, the mast that would probe the ocean sky for 50 feet above, the cockpit depressed below the deck to shield from seas and drain away, by hoses down through the hull, whatever spray and breaking waves might come her way.

Billy’s father, older than when he sailed her to the Caribbean for many winters, had fewer ambitions. Just a cruise up to Maine for the summer, that was all. Barry didn’t know why he had so much time on his hands, freeing him for weeks of sailing. It made no difference. When you’re at sea, it doesn’t matter what happens on land.

Ten days later they boarded shortly after dawn, stowing their duffels and packing food and ice behind secured lids and locker doors against the rolling and pitching to come. By 8 they had cast off their lines and eased out of the slip, and then, their diesel engine clattering, motored through the twisting channel and out into the teasing swells of the broad Atlantic, where they hoisted the main, unfurled the jib, and turned northeast into the wilderness.

This moody stretch of ocean is named euphemistically the Gulf of Maine. It is the Atlantic Ocean in all the alluring temptations and caresses and furies that the Atlantic has given sailors since the Vikings piloted their sleek and slender ships through fickle northern latitudes, since American Indians labored their canoes through millennia to outer islands. The Gulf of Maine is nourished by two great rivers in the sea: the Labrador Current, which curls down around Newfoundland and Nova Scotia’s Sable Island to channel frigid water along the Maine coast, and the tepid Gulf Stream, which swoops up and forms a flowing boundary to the south. Caught between the two, the ripping tides roaring down and up the Bay of Fundy stir and thrash. When the Gulf of Maine is tender, it is embracing, like a lush and sunny field. When it is angry, it is primitive. “Respect the water, Barry,” said his camp director, Larney, a browned and brawny man with calloused palms. “Respect the water.”

Barry rode the long rhythm of the swells with keen euphoria, like a symphony’s slow and gentle movement that stirs an eager pulse. The sloop’s 35 feet seemed to shrink and expand at once, tiny yet sheltering, a speck on the vast watery surface and yet an entire enfolding realm. He was conscious of two horizons: the one reaching out to infinity—where on a hazy day like this the blue of the sea and the blue of the sky nearly blended together at the edge of reality—and the one aboard, where a sound vessel drew close limits of comfort and trust.

The voyage would take about 30 hours. First, the day. Then, the night. Finally, the second day whose light before dusk would guide them into safe harbor. They wanted wind, needed wind, to make the timing work.

Nick strutted, Barry noticed. He postured, leaning against the mast with casual ruggedness. But not smoothly, not gracefully while he moved around the boat, as if all his bulging muscles had lost their memory of how to step up and over coaming from the cockpit to the deck and back, of how to winch quickly and how to cleat a line flawlessly. His beefy hands fumbled a little at the winch and cleat, while his manly talk with Billy and his father seemed contrived to cover awkwardness. His balance gave a little as the Spray began to roll and pitch—just a little, not enough to stumble, just enough to make Barry wonder.

Every boat is different, yet the sea treats all boats the same. It plays with them as it wishes, so sailors on whatever craft must learn the cadence of the swells. On the moving deck, Barry was as sure-footed as a dancer. With a magician’s dexterity above the winch, he dropped one, two, three coils of supple rope instantly around the drum, then pulled them tight. As fluid at the cleat as a weaver, he used a single flowing motion to wrap the line in a circle beneath the cleat’s two horns, then crossed it diagonally above, made an opposite diagonal on top, flipped the bight of the rope beneath a third crisscross, secured the clean figure eight with a fourth diagonal and a final circle, and pulled back triumphantly to see if Nick had seen.

He had. He tilted his head just a little and raised one eyebrow, a talent Barry envied.

The first hours at sea are always eager hours, the crew jaunty, the boat liberated and lively in the waves. The gleaming black fins of dolphins now and again above the surface made them point and shout. They peered hard in search of smoky wisps of spray that might mean spouts of whales. Rotating jobs, they settled slowly into the pace of the morning, then midday. The following breeze barely tickled the back of Barry’s neck.

Nick was supposed to tend the jib but wasn’t watching the flutter, the luff. “Can you come in with the jib?” Barry asked from the helm. Nick gave him a quick glare, glanced at the sail as if seeking evidence to rebut the request—the command. But then shrugged, grabbed the winch handle, and gave a defiant half turn. “A little more?” Barry said.

“It’s fine,” Nick growled.

“No, another turn or two,” said Billy’s father. Nick spun the handle twice around, rapidly to show his strength. The jib, now taut as a white bird’s giant wing, flew high without the hint of tremor. Nick shot Barry another glare, then whispered to him below the threshold of the rushing sea and wind, “It was good enough for government work. We’re not racing, you know. Don’t stress.”

Barry’s smallness did not feel as feathery as usual. His steering on the wide, spoked stainless wheel came instinctively, without the labor of thinking. The morning haze had cleared, the wind was steady now off the starboard quarter in a comfortable broad reach, the Spray’s favorite tack. The following waves nudged the boat to the right and left off her heading as the stern was pushed gently to port by the waves behind, then to starboard in the troughs. A good helmsman finds a complementary tempo, leaning and turning the wheel left, then right, then left to hold the boat on course in sympathy with the following swells. So it was with Barry, somewhat to his surprise, his small body tuned to a simple reflex as he rode the wheel and the rising seas.

And rising they were. Spelling one another on the helm, the crew allowed their talk to ebb throughout the afternoon. One by one, they went below to nap in expectation of their coming watches in the night. Above, the water’s cobalt blue mellowed, the sun began its slow decline over their shoulders. The wind speed on the gauge grew gradually to 18, 20. Gusts made it jump higher and higher in brief bursts, as if playing with limits. And the wind backed around until it was blowing from directly aft, making a run that forced them to sail wing and wing, the main out to starboard now, the jib to port, the stern lifting higher and higher with every surging wave, then sliding into every trough with a hiss of foam. The seas were building behind them. The boat was surfing down the steepening waves. Steering grew more difficult.

“Who wants to set the boom preventer?” Billy’s father asked, looking straight at Nick—the biggest of the lot, the most muscular, the daring combat soldier who had faced a lot more danger than this. But Nick looked down, then away at the seas. Foam was blowing off the crests. The boat was leaping. Billy, leaning into the wheel, struggled to turn the bow down the steepening slopes to keep her from sliding sideways recklessly into the valleys of the waves. There were no other candidates. Billy, straining against seasickness? Barry, as slight as a matchstick in the hum of wind? Billy’s aging father with shaky balance?

“At sea, no problem goes unsolved,” Larney had once told the boys around the campfire, “or it could be the last problem that you’ll ever have to solve.” The slow, weathered voice drifted into Barry’s memory along with the low whistle of the wind in the shrouds. Larney’s tales of the Pacific had the boys crouching forward toward the flame-flickering reflections of a face jagged in the night. The thick eyebrows, like grey ridges, cast his sunken eye sockets into ravines of such shadow that the little light finding his eyes made them glint impishly as he told his sea stories—tales, they knew, that would always come out well.

The mainsail on a run in a wild sea was a problem to be solved. The boom, far out to starboard to catch the following wind, swung dangerously aft again and again as the rollers lifted the stern and spun the boat this way and that. A wave tossed the stern left and put the wind to starboard, the mainsail went slightly slack, the boom reeled toward the stern, and then as the stern lurched to the right, away from the wind, the boom swerved sharply back to starboard until it was snapped to a stop by the braided rope of the mainsheet. Every time, the mainsheet twanged out tensely. Nobody worried that the line would break. It still had the pliability of newness, showed no chafe, and was threaded back and forth four times through stainless steel blocks. But the hardware might be in question: the shackles, the cotter and clovis pins, the swivels. Hidden corrosion could make them fail, and when a critical piece of steel gave way, Larney had told the boys, the sound was like a gunshot. All this Barry remembered as he braced himself in the bucking cockpit, marveling at the shocking blue and white of the Gulf of Maine.

The near jibes were not good for the sails. As the boat rolled and yawed, the mainsail lost wind, and so did the jib. Then they would snap full again, luff, then snap, luff, then snap. And if in its swinging, the heavy aluminum boom ever reached amidships close to the stern, and the wind caught the sail from the opposite side, the boom would jibe and roar across to port with enough force to test the strongest rigging. All four of this crew could imagine the worst, which is what you have to do at sea. It could rip out the bolts holding chain plates to the deck, and since the wire stays from deck to high on the mast were held taut by those plates, any failure would transform a stay into a loose and lethal cable swirling like a whip against all else aboard, metal, fiberglass, and flesh.

The problem had a solution, as Barry also knew from racing small boats. But here on this wildly frolicking ocean, this ocean that hadn’t even yet turned mean, it was a risky solution to perform. Step out of the protected cockpit, up on the adjacent narrow deck, work your way forward to the boom, staying low so a jibing boom would pass over your head, not into it. Move to the foot of the mast and grab the small lanyard on the pin of the snap shackle that held one end of the block and tackle—the boom vang—whose other end was fastened to the bottom of the boom. Pull the lanyard on the pin to open the shackle, then step to the starboard gunwale, the very edge of the boat, the edge of the world of safety, feed the hook of the shackle through the oval stainless ring secured there, and click it closed. Then pull hard on the bitter end of the line through the blocks until the boom vang, now converted into a boom preventer, was tight enough to keep the boom from swinging aft.

“Whose gonna set the preventer?” Billy’s father asked again, looking straight at Nick. But Nick did not meet his eye. He pretended to busy himself at a winch, tending the jib sheet. Silence in the shoosh of foam and wind.

“OK, I’ll do it,” Barry finally shouted and waved toward the bow. “Somebody take the helm. Nick?”

Nick leapt for the security of the wheel, grabbed its cold curve of shining steel, jostled Barry out of the way like the linebacker he used to be, and held on as if the helm were a sanctuary. But instead of riding with the following sea, he wrestled against it. He spun the wheel too far to starboard, too far to port, the stern flung itself back and forth, the main sail fluttered for a moment as the boom swung dangerously, then snapped full as the boom careened back to its proper place. Barry eyed the frantic deck he was to navigate.

“Let me,” said Billy’s father. “We don’t want to dump your brother overboard when he goes forward.” The man, trying to laugh, stepped up and over the cockpit benches to the wheel and steadied it with a practiced grip. Nick gave a stricken look as he stood aside. In the father’s hands, the Spray quickly settled into a rhythm, lifting, falling, rolling, yawing in a predictable tempo that felt reassuring—a small boat’s harmony with a following sea.

“No!” Nick yelled to Barry. “I’ll go, kid. Stay here, safe and sound. I got it.”

“Harness,” said Billy’s father. Nick wormed his way into the webbed belt and shoulder straps, secured one end of a tether to the immense buckle at his belly, and clipped the other to a jack line of cable they had rigged for just such an occasion. Shackled in the cockpit, the wire ran along the deck to the forward most cleat at the bow. Nick clipped himself in and stepped out of the cockpit onto the narrow deck.

“Stay low,” commanded Billy’s father. “At least one hand on the boat at all times.”

That was all very well, Barry thought, but Nick would need two hands to pull open the little shackle holding the boom preventer’s block to the mast, and probably two hands to close the shackle around the ring on the gunwale. Why the hell didn’t we do this before, when it was calmer? Larney’s voice again: Act when the idea first enters your mind, don’t wait. Reef the main as soon as it occurs to you. Rig the boom preventer whenever you’re sailing on a run and the seas build.

Nick crawled. Barry thought he must have done that in Vietnam, snaking along the ground, bullets whizzing overhead. Belly down, Nick stopped halfway to the mast and turned to look back at the cockpit. Yes. His eyes were frozen wide the way dead people look in movies before somebody thoughtfully touches their eyelids closed.

He took forever to reach the foot of the mast, and then he hugged it with both arms. He had no hands left to manipulate the shackle. The boat was trying to hurl him. At last he released one arm, fiddled with just one hand but couldn’t pull the pin. Again he hugged the mast. Again he glanced back at the crew in the cockpit with a paralyzed look.

“I’ve got to go help him!” shouted Barry. The father didn’t say no, he just said, “Harness.”

Out of the shelter of the cockpit and higher on deck on the way to the mast, Barry felt more fragile surrounded by the ocean’s boiling temper. He gripped the rail of varnished teak handholds, affectionately maintained for the aesthetic tastes of fair-weather cruisers. A tiny revelation stung him with amusement: that the gleaming brightwork he admired was absurdly precious here, against the sea’s indifference.

At the base of the mast, he touched Nick’s shoulder and felt an arm grip around him. “Hey, kid, what are you doing here? But thanks for dropping by.” Barry waited for a steep roll and pitch to pass, then reached both hands for the shackle, pulled on the little lanyard to yank open the pin, clutched the detached pulley to his chest, and—using one hand again to hold desperately the gloriously varnished rail—wriggled down to the narrow lower deck to reach for the silvery ring.

Funny how strange thoughts wisped through his head, like spindrift blowing from the crests of breaking waves. The ring, the eye nut, marked the farthest edge of his life. Just beyond, over the gunwale, roared the mounting anger of the following sea. And the Spray was trying mightily to toss him as casually as a bronco might flick a cowboy. His tether would not keep him aboard; it was long enough that he would merely be prevented, once in the water, from drifting away. In fact, as he knew from Larney’s tales, he would be slammed against the hull again and again and would survive only if his shipmates were quick enough in hoisting him back up to their refuge, which was bobbing and twirling like a toy. He saw Nick still above, now crawling back toward the cockpit.

A wave crowned over the stern, sending green water swirling up the deck and bathing Barry in iciness, curiously refreshing. He rolled toward the horizon, then back inboard, and reached through foamy chaos with both hands on the shackle, fed its hook through the eye nut, clipped it closed, and pulled hard on the rope through the pulley, holding it like a lifeline as he backed down and tumbled over the coaming into the safety of the cockpit.

A cheer went up in celebration. Nick slapped him on the back and gave him a long look that Barry had never quite seen from him before.

Meals at sea were kept simple. A pot of chili heated on the stove, ladled into bowls, wolfed down while bracing against the tossing, pitching, rolling, every muscle active in the struggle—the beautiful struggle, in Barry’s mind. He felt at one with the boat, like a rider attuned to a galloping horse. He wanted to inhale the lingering twilight, to keep the enchantment inside him.

The ocean darkened. “Come on, kid,” Nick ordered, “let’s get some sleep before our watch. So you don’t fall asleep on the wheel!” But who could leave the canopy of stars that floated above them, the embracing belt of the Milky Way, the wind whistling in the shrouds, the whisper of the water past the hull? “Come on, kid. I don’t want a guy with me who can’t hold his own.”

Sleep did not come easily, but it came. Every lurch, every blunt knock of wave against the hull, every slap of halyard on the mast above, every call from Billy or his father to haul in or loosen, to watch a distant set of running lights that might mean a vessel trawling—every one of those little alarms would have shot a pulse of tension through a skipper’s shallow sleep and had him nearly on his feet and topside. For a while, Barry lay rigidly in his sleeping bag, listening to all the sounds as tightly as a skipper would. But he was not the skipper, and eventually he drifted off.

A hand shook his shoulder. “Midnight,” said a voice, kindly and perhaps apologetically. Barry did not yet know a fact about this moment: It was never pure pleasure to wake the next watch, but not a regret either. It was one of those cruel duties, which, for anyone with both self-interest and a heart, brought an odd mixture of relief and sympathy.

He pulled on a slicker, rain pants, and boots against the spray and the heavy dew of the night. He buckled on his harness, wedged his shoulder against the rolling companionway for balance, and climbed the three-step ladder out of the compartment and into the wild. The air hit his face joyfully, fresh and damp. The stars were whirling above, the sails ghostly in a shallow moonlight, the running light atop the mast twisting back forth against the Milky Way like a firefly.

Nick was there already, tense. Billy’s father gave the course, reminded them to mark their position on the paper chart below every hour, and pointed slightly aft to fuzzy lights way off, appearing and disappearing behind the waves. “Fisherman. We passed him. Nothing else around.”

“Sleep well,” Nick said, a note of false bravado in his voice. Billy and his father disappeared below, slid the hatch closed, and sealed the brothers into the long struggle of the midwatch.

The wind still came roughly from behind. Barry blinked in alarm at the glowing digits showing the speed. What had been a steady 20, 25 in daylight now held at 35, 37, and—a second or two after a gust made the rigging scream—the number jumped to 40, 42. The seas had swollen, too. In the dim light, he had to look up to see the crests of the waves, which chased them and curled with teasing menace at the stern. The boat careened, forcing every muscle to work without pause.

Barry began the watch at the wheel, riding the bucking hull by bending one knee, then the other, to stand upright wh