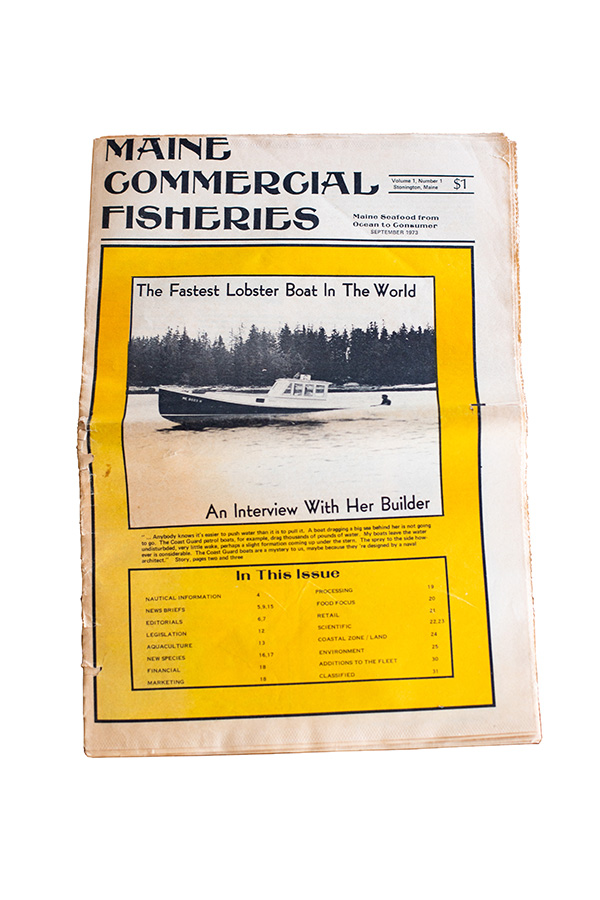

I have been looking back at what fishing was like in 1973, the year I founded Commercial Fisheries News. The differences are stunning, even to someone like me who reported on those changes, sold ads for the new gear, was part of creating the new lobster laws in the 1990s, and tried to connect fishermen so that they could contribute to better science and better rules.

As the lobster fishery fights for its existence while confronted with new whale rules, declining prices, and biological indices—and stunning costs— looking back with that 50-year perspective can help clarify what is deeply important about lobstering and the strengths fishermen possess to meet a time of such profound change.

Fifty years ago, lobstermen were fishermen. If a lobsterman wanted to make more money than he could by lobstering, he could go tub trawling, gillnetting, or dragging for groundfish, scallops, and shrimp. There were herring to catch in stop seines, clams to dig, and mussels, especially once the state developed a market for that shellfish in the 1970s. Fishermen had the freedom to do that: Maine offered only three license types: lobster, commercial fishing, and commercial shellfishing. All were open entry.

Fishermen gained a lot of knowledge from having that versatility. Observations of a fisherman working in one fishery in an area gave him useful knowledge about other fisheries. Fifty years ago technology hadn’t overwhelmed the skill that comes from direct observation and a good memory; the skill, for example, of finding your traps in a fog mull without radar, Loran, GPS, or Olex sonar. Just a compass, running time, your flasher, and alertness—sound, smell, bird activity, the feel of the tide and the sea.

Fifty years ago, more than half the new lobster boats were wood, virtually all in the 30-foot to 36-foot range. There were only a few new fiberglass models on the market: Repco 30 and 37, and one hull each from Webber Cove, Jarvis Newman, and Bruno and Stillman. Most new lobster boats had gas engines, diesels only if the owner planned to pursue other fisheries, too. Traps were wood, mostly built or repaired in the shop each winter; heads were knit at home. Buoys were transitioning between wood and Spongex. The first Friendship Trap ad for wire traps showed up in Commercial Fisheries News in 1977.

The Coast Guard was going town-to-town in 1973, introducing the new Loran C technology. Only draggers had used Loran A at the time, so initially the change didn’t mean much to lobstermen, whose only electronics were a flasher and for some, a CB radio. Today’s fleet of lobster boats may look quaint to a tourist but there has been a technological explosion in the last 50 years. Contrast the boats of the 1970s with today’s wide, able 40-foot to 50-foot boats, complete with trap racks and 600- 800-plus horsepower clean diesels, with radar, GPS, sonars, radio, cell phone, and even computers aboard, fishing 800 wire traps delivered complete from the factory.

There has also been an explosion of lobster. Most lobstermen today have only fished when landings have been increasing. Today’s Maine lobster fishery is catching more than six times the poundage being caught 50 years ago: increasing from 17 million to 109 million pounds. Why? Probably because of Maine’s good management that protects breeders and juveniles accompanied by climate-related changes in the Gulf. The price, until 2022, has kept up with inflation so that, in real terms, the Maine lobster fishery is bringing in over six times the money to coastal towns than it was in 1971. When has there ever been such a long run of good times in a fishery?

A third explosion occurred in government; the world of 50 years ago is unrecognizable today. When the Maine Department of Marine Resources (DMR) was created in the early 1970s out of the Department of Sea and Shore Fisheries, DMR was given rule-making power. Before that, fisheries rules seldom changed because virtually any changes had to go through the state legislature. At the federal level, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, and the Endangered Species Act all were enacted in the first four years of the 1970s. The Maine-New Hampshire border hadn’t been settled and it was almost another 15 years before the U.S.-Canadian boundary line went into effect. There were 200-250 foreign vessels fishing in the Gulf of Maine and on Georges Bank every month, including factory trawlers, purse seiners, mid-water trawlers, and others, each vessel hundreds of feet long. Fish stocks were depleted. A foreign captain complained that his tows had dropped to only five to 25 tons.

Maine lobstermen lobbied for a federal law to declare lobster a “Creature of the Continental Shelf ” and led the first leg in a “sail-in” to Washington with other East Coast fishermen. After years of outcry, the Magnuson Fishery Conservation and Management Act went into effect in 1977, putting in a 200- mile limit that excluded foreign boats.

The new law also created the New England Fishery Management Council. The council brought a type of management that had never existed before in New England: permit purchasing, individual transferrable quotas, quota leasing, and consolidation. Over time, the approach virtually eliminated Maine’s small-scale dragger, gillnet, and herring fleets, while allowing stocks of cod, haddock, and herring to plummet in the Gulf of Maine.

Lobstering avoided this fate as a result of dogged determination by Maine Lobstermen’s Association (MLA), led by Ed Blackmore of Stonington who was on the council. He achieved wins that we take for granted now—protection for V-notch and oversize lobsters and limits on dragging for lobsters. Each was a multi-year battle.

Especially critical was that lobster management outside three miles was removed from the council’s oversight and its federal management approach and transferred to Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC), a compact of East Coast states. Once in ASMFC, Maine state rules were extended out to 25 miles offshore. Along the way, the fishery added vents to traps and increased the minimum size of lobsters. Initially, many lobstermen vigorously opposed both measures.

In the mid-1990s Maine faced tremendous pressure to limit entry and put in a trap limit. Once again, with leadership from the MLA and many lobstermen, Maine went a different way. Entry was controlled through apprenticeship; owner-operator was put into law and Maine licenses couldn’t be traded. The trap limit was set at 1,200, to be gradually lowered to the current 800. Though many realized the number of traps was probably too large, at the time it was the lowest number that could pass the Maine legislature. Each zone council was given the right, which they have still today, to vote in a lower trap limit. Only Zone E has done so.

Fifty years later, lobstermen now operate within a set of very complex rules. Gone is the anonymity of fishing without electronics, with new whale rules and trackers continuing the trend. Few lobstermen today are also fishermen. They have virtually no options to diversify in federal waters (outside three miles). State water fisheries cannot match the opportunities of the booming lobster fishery of the last 25 years.

Now, after 50 years of good times, lobstermen are facing daunting debt and an uncertain future in the face of climate change. All that is terrifying. Making a living in a wild-caught fishery is never guaranteed. This is the hard part of fishing, which some older fishermen remember well.

Yet, 30 years ago Maine lobstermen created and stood up for changes that have given them important resilience and a model for the future. They created something new in fishery management, based on what they wanted the business to look like. The result? Lobstering has prospered in communities the length of the Maine coast.

Without this vision, the explosion of both lobsters and technology over the last 50 years would have resulted in a consolidated, corporate lobster fishery based in a few big towns, with far fewer fishermen, and most working as employees, and our towns turned into tourist traps.

On top of all the rules that protect lobster biology, lobstermen stood up for and got these other principles passed into law in the 1990s:

- Owner-operator is key to keeping lobstering in coastal communities

- Apprentice-based entry to require a commitment to the business

- Across-the-board trap limits to ensure skill, not your bank account, determine how much you catch

- No transferable licenses or traps, to prevent consolidation and make it affordable for young people to start out

- Lobster management zones to keep lobstering opportunities in local communities

- Lobster zone councils to recognize area and fleet diversity and give lobstermen a voice about issues in their area, which differ along the coast.

None of this was easy—4,000 to 5,000 independent people, their crews and families didn’t, and won’t ever, speak as one. But as all of us enter this new world of climate-related changes in the Gulf of Maine, it’s worth acknowledging the creativity and leadership it took to get where we are.

The Gulf of Maine is a natural system, not just a place to steam over to go take lobster. Who can deny that our technology today has the ability to overwhelm any natural system? The problems don’t all come from the government; sometimes they come from us. As the ocean changes, we will all need to learn and adapt as we go—fishermen, scientists, and government.

The lobster fishery has always shown it can lead with humility and creativity, as well as with power and anger. It can chart an ecologically and community-centered future for those of us who fish.

Robin Alden founded Commercial Fisheries News, a Northeast regional trade newspaper in 1973. She served as commissioner of the Maine Department of Marine Resources under Gov. Angus King from 1995 to 1997. In 2003 she established Penobscot East Resource Center, now known as Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries. A version of this essay first appeared in Landings, the monthly newspaper of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association and is reprinted with permission and gratitude.