Eva Murray moved to Matinicus in 1987 to take a position as the school teacher. Matinicus then was similar to Matinicus now: a small island fishing town, 15 miles out to sea, resplendent in natural beauty and with a powerful sense of community, yet lacking many basic services. Medical care was nonexistent. When Murray arrived, there was “no one to go to if you got hurt, or got a burn – no one had any training and certainly no one had any obligation” to help. A program that had brought licensed nurses to Matinicus had lapsed in the 1970’s, and so island residents needed to rely on being able to get off Matinicus for serious medical attention. “We were the backcountry,” Murray explained. “Being on Matinicus was very much akin to mountain climbing – whether you can get off the island or not was almost entirely dependent on weather.”

Each of Maine’s island communities faces challenges unique to each situation. But one incontrovertible fact unites all of them: no matter the mode of transport, it takes time to get to the mainland, and it’s that time that consumes the thoughts of island first responders like Murray. It’s what makes it difficult to receive proper training. It’s what makes an emergency 9-1-1 call take multiple hours. And it’s the reason on-island, dependable Emergency Medical Services are so important: because they are not a ferry ride away, they can get to the patient much faster than anyone else.

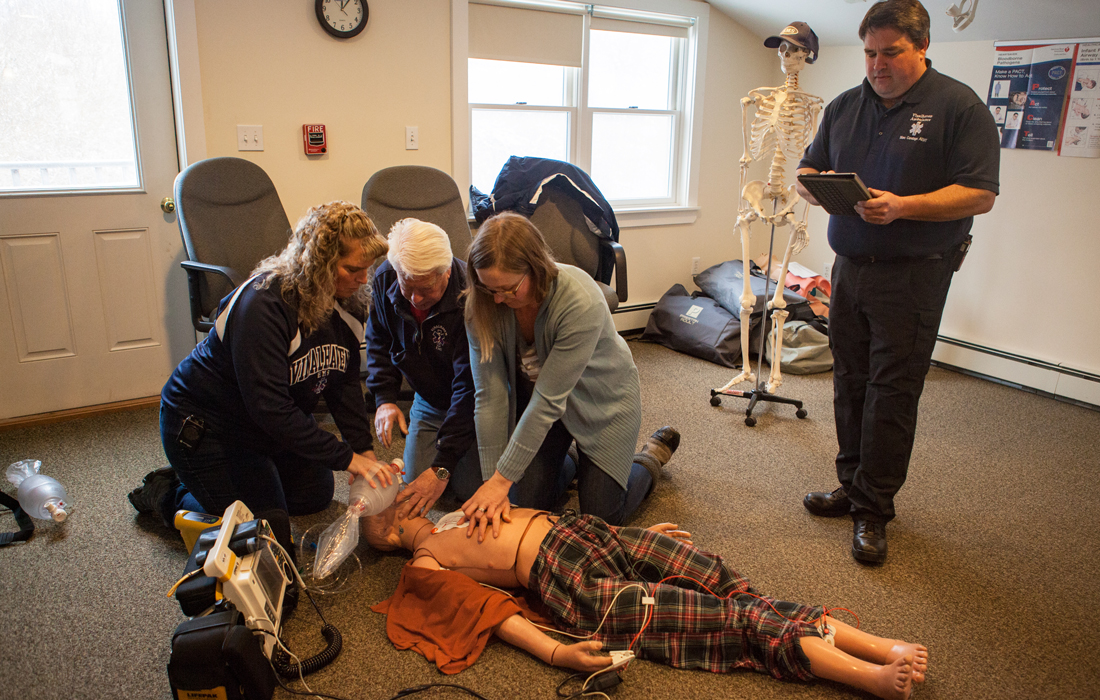

In 1994, after nearly twenty years of no medical care on Matinicus, Murray and four other residents got together and advocated for a licensed paramedic to come to the island and offer EMT training. This was both an essential service and it circumvented the first challenges facing island first responders: how to receive adequate, on-site training. Daily ferry trips are prohibitively costly – both financially and temporally. Having someone come to Matinicus guaranteed that more people would be interested.

Five people signed up, but what they didn’t realize when they started training was that they would be forced by law to form a state-sanctioned ambulance service.

Maine law holds that a Basic EMT needs 52 hours of continuing education every year to maintain a license. This training needs to be documented, certified, and archived. Only a few months after the five trainees on Matinicus received their licenses, Matinicus Island Rescue was born. Because it was a was a registered place of work, Matinicus Island Rescue also had to observe Bureau of Labor Standards. If an organization fails random BLS check-ups – which can happen when one or two people are in charge of all administrative, operational, and financial duties – then it is subject to fines. As Murray recalls, those five original trainees “had to become EMT’s in every sense of the word,” which turned out to be much more than anyone had expected. Ultimately, administrative demands became too much for Matinicus Island Rescue, and the service was disbanded. Today, Murray is the only licensed EMT on Matinicus.

That Matinicus had a cohort of enthusiastic citizens prepared to dedicate their time to emergency services yet couldn’t make it work speaks to the second – and most correctable – challenge facing island EMS departments. Maine laws hold small volunteer EMS departments like Matinicus’ to the same standards as large city departments. Comprehensive documentation is vital in any industry – especially in one with such high stakes, like EMS, but some leeway must be made for tiny departments serving remote areas. Less detailed recordkeeping is surely better than having no EMS at all.

On larger islands, the calculus shifts slightly; paperwork and administrative duties still take up a lot of effort for Swan’s Island’s and Vinalhaven’s Ambulance Services, but, by far, their biggest obstacle is a lack of volunteers. This, too, can be traced back to time. A typical call for Swan’s Island EMS will have EMTs on scene in five minutes and the patient stabilized in ten. But the subsequent trip to the mainland in the ambulance on the ferry might add three or four hours. And even though Vinalhaven has a medical center with a minor emergency room, Vinalhaven EMS director Pat Lundholm says, “A morning call around 8:45 requires that you be off island until 2:30 or 3.” Those additional hours may not seem like a lot, but those are hours that could be spent working a job or spending time with family. Of course, responding to an emergency is well worth it, but that people don’t step up to volunteer is not a surprise. They simply don’t have the time.

Still, looking at how island communities react when something does go wrong, it’s clear that distance to the mainland isn’t the only trait these islands share.

Frenchboro’s Zain Padamsee described what happens when there is a fire on an island with no formal fire department. “One person runs and gets the brush truck, and another person calls everybody on the island, and everyone who’s on the island shows up and starts doing what they can – it’s a complete town effort.”

On Matinicus, there may not be an ambulance service, but Eva Murray still provides emergency care. “There are some heartbreaking sides to it,” she said. “Sometimes, I see friends and neighbors at their lowest. But being the one who can comfort them as they’re evacuated more than makes up for it. It feels good to be the one who can help. It feels like being a good neighbor.”

And on Swan’s, where I lived for a year as an Island Fellow and a member of the Fire Department, I’ll always remember one of my last days on the island, in the heat of August. After almost twelve months, it was my first fire call.

The scene was at a far end of the island, and as I drove over I wondered at the lack of other cars on the road. I was worried we wouldn’t have enough people to fight the fire, that people were out lobstering and hadn’t heard the call or couldn’t get back to the harbor in time.

But when I rounded the last turn, I saw as many cars as I’d ever seen parked in one place on Swan’s. I saw the cars of people in the fire department and the cars of people not in the department, of fishermen and fisherwomen, carpenters and teachers. While it was only the members of the fire department that were doing the actual fire-fighting work, seemingly the entire island had shown up to see if they could, in some way, help.

A father and his son – both still in fishing gear – told me the situation was under control. It had been a minor brush fire.

Being a small island community often means that the resource in shortest supply is people. For EMS, due to the administrative responsibilities and runs that last twice or three times as long as they would for mainland departments, this means that a disproportionate burden falls on a few dedicated people. That makes day to day operations of an island EMS service exceedingly difficult. But that day on Swan’s Island, I know that all of the people who showed up reacted instinctively. Even on a larger island like Swan’s Island, there are simply not enough people to think that someone else will answer the call. That’s how islands work. When help is needed, it is given – and given unreservedly.