My eyes are brown. The eyes of my two brothers are pale blue. I see the world differently than they do, but that is a matter of gender and life’s experiences, not in the nature of our eyes.

When I was a child, I attended Sunday School in the parsonage of a small Congregational church. I recall one day when sunlight through the tall windows struck dust motes in the air, turning the narrow room into a valley of white light. I was five years old, ensconced on the floor with a bevy of other small children, making the clumsy handicrafts of the very young. The light, however, drew my attention away. The windows and the room were full of brilliance and I was astonished and wordless. At that age, I had no voice for my perception.

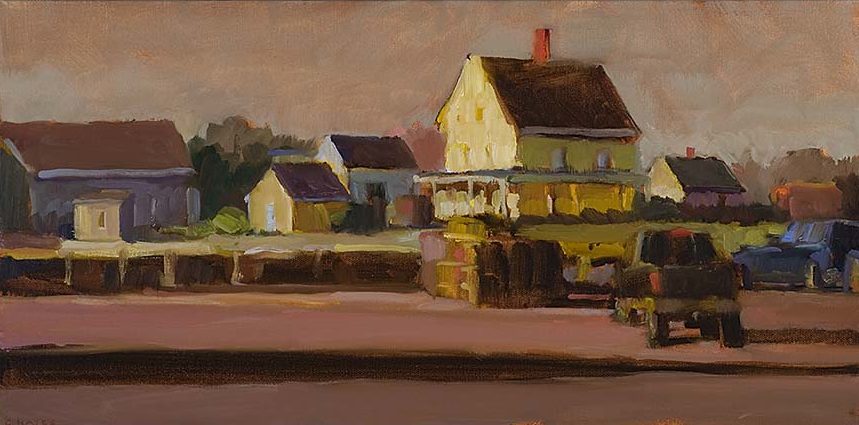

Artists don’t need words, although many wax loquacious in their “artist statements.” Maine artist Connie Hayes is parsimonious in her speech. A small woman whose light grey eyes seem large behind her glasses, Hayes leads a painting group on Vinalhaven for two weeks in June. She came to the island years ago during a time of peripatetic wandering along the coast. Hayes stayed in the homes of friends and acquaintances to paint what captured her attention in those locations, setting up shop from Stonington to Cape Elizabeth. The result was the “Borrowed Views” painting series, captured in a book of the same name.

During her time on Vinalhaven Hayes stayed at a friend’s house in Old Harbor. And that’s where she met Addison Ames.

Ames is a lobsterman and forester. He is a lean man, hard-forged, who moves fast and speaks fast, his full Maine accent occasionally obscuring his words. Unlike Hayes, he enters into conversation at full speed, telling stories, jokes and quips at a galloping pace.

Ames was using the wharf that was part of the property where Hayes stayed, landing his lobsters and storing gear there. One day he went up to the house and introduced himself. Soon, Ames was visiting with Hayes in the evenings after he had put his boat on the mooring. The lobsterman and the artist talked about those things that islanders think about: the weather, the ferry schedule, the vagaries of island living. And about art.

Ames has dark eyes. Like many lobstermen, he moves his body carefully and with great efficiency of effort. As he recalled, Hayes’ paintings affected him like an itch.

“I wanted to understand how it was done, how it worked,” he said. After all, Ames is known on Vinalhaven as the “tree curator.” With his brother Danny and other members of the family, he runs a company in the winter that does site clearing and forest maintenance—“landscape forestry,” as he terms it. To his business he brings the talent of vision.

“The woods talk to me,” Ames explained. Before he begins clearing, Ames will walk the land to know it and to ask questions. Where can one see the sun and when? Where is the water? Where are the rock formations or level ground? He is not there to scrape the land clean but to shape it to an image he carries in his mind.

The lobsterman and the artist talked about those things that islanders think about: the weather, the ferry schedule, the vagaries of island living. And about art.

“You discover things when you are out there,” he said, “plus there’s the history of who was there before. I’m often just copying what the old folk did before me.”

Hayes and Ames became friends. The artist and the lobsterman shared a sense of the numinous. Hayes pursues what she terms “perceptual painting.” Perceptual painting means watching and waiting for the crux of the thing, whether it is a house, a boat, or a bunch of boxes leaning against a wall, to reveal itself. It is the moment of astonishment that the artist tries to transfer to canvas.

Ames invited Hayes to come with him to certain spots on the island where she might find a subject to paint. Occasionally, he would row Hayes to Greens Island, knowing there was something special there for her. The route took them past Burying Island. At times, the compact little island caught the afternoon sun; at other times fog drifted past in thin ribbons.

Hayes’ trips with Ames and throughout Vinalhaven produced paintings of seeming simplicity that are a far cry from the pretty scenes so often associated with the island. Vinalhaven’s beauty seeped through Hayes’ strong colors and shapes, not in dainty lines.

“Surface appearance and deeper understanding are two very different levels of knowing that can blend in the process of painting,” she explained. “That process can help to keep picturesque sweetness at bay,” a quality that may be hard to avoid in an island landscape.

“Seeing and looking are different things,” she said. “Looking comes from you. You look at a house. Seeing comes from the object back to you.” To see means to apprehend something ineffable about the object viewed. That is the core of an artist’s ability. The eye sees more than is evident. The commonplace is not common.

On a fine summer day, I sat waiting for the ferry to carry me from Vinalhaven across Penobscot Bay. I had tromped about for hours, visiting the historical society, the Carver Cemetery and Lane’s Island Preserve. I was tired and to rest my eyes, I took off my glasses.

I have worn glasses for nearsightedness since I was very young. They link me to the real world—without them, objects lose their definition and become something… other. That afternoon the sun’s rays bounced in fuzzy halos off the rocks around me. The ferry coming ‘round the point was a figment of white passing over a swath of blue. A nearby pile of color that I knew to be a collection of lobster trap buoys took on another meaning, one that again, I could not put words to. I didn’t want to. Astonishment is always there. You just have to see.