In 2002, Natalie Springuel and Richard MacDonald, among others, embarked on a paddling expedition along the shores of the Gulf of Maine. Today, they are a married couple, and what they learned then—and what has changed since that journey—reveals how dynamic and threatened is this “semi-enclosed sea.”

NATALIE: The 2002 Gulf of Maine Expedition was a sea kayaking journey organized to raise awareness and caring about the ecological and cultural legacy of this vast international watershed and to promote low-impact coastal recreational practices, safety, and stewardship principles.

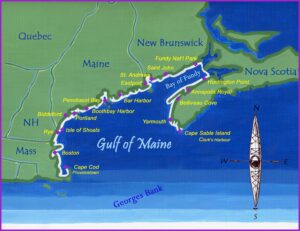

Over the course of five months, our team paddled the perimeter of the Gulf of Maine from Provincetown, Mass., on the tip of Cape Cod, along the Massachusetts coast through Boston Harbor, north along the 18-mile New Hampshire coastline, the entire coast of Maine, across the Canadian border and around the Bay of Fundy from New Brunswick to Nova Scotia, finally finishing at Cape Sable Island, the very end of the Gulf of Maine.

The expedition had numerous sponsors, including our principal sponsor, Maine Sea Grant (still my employer today more than 20 years later). We also had support from Maine Coastal Program, Gulf of Maine Council on the Marine Environment, Maine Association of Sea Kayak Guides & Instructors, and Maine Island Trail Association, as well as dozens of other organizations and individuals.

After a 2001 article in Atlantic Coastal Kayaker, volunteers seemingly came out of the woodwork. We received time from an AmeriCorps volunteer to support media and educational outreach. Another volunteer tackled what proved to be the daunting task of finding camping opportunities along the Massachusetts portion of the journey. We also benefited greatly from equipment sponsorship from 14 product manufacturers, including Necky Kayaks and Kōkatat.

Over the course of five months, we paddled over 1,200 nautical miles, made an estimated 1.3 million paddle strokes, conducted 24 community events (largely in partnership with local organizations), and met countless people.

I am grateful to my employer, Maine Sea Grant, for sponsoring the expedition. Today, I serve as the organization’s marine extension program leader. Rich runs The Natural History Center, leading birding, nature, and adventure tours in Acadia, Downeast Maine, and beyond, from the Arctic to the Antarctic. He proposed to me in month four of the trip, in Nova Scotia’s Tusket Islands. I said yes. We have been adventuring together ever since.

on Saquish Head.

RICH: Provincetown, Mass. On a cool, clear May 2002 morning, four paddlers stood on a Cape Cod beach trying to figure how to stow a mountain of camping gear, clothing, food, monitoring equipment, and a laptop into three kayaks, each with bows emblazoned “Gulf of Maine Expedition.”

This five-month adventure was the culmination of Natalie’s dream to raise awareness about the ecology and cultural legacy of this 1,500-mile international coastline. Now, 20-plus years later reflecting on the adventure, we are struck by the changes between then and today, especially some of those that were not on our radar at that time.

NATALIE: The 1990s saw a sea kayaking explosion and I was in the thick of it. I was making my living as a guide, a profession not as well established as other marine work but no less dependent on understanding the Gulf of Maine. As kayaking was booming, so too was our knowledge of the Gulf of Maine as a unified geography. In 1989, the Gulf of Maine Council on the Marine Environment was created by the governors of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine, along with the premiers of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, “to foster environmental health and community well-being throughout the Gulf watershed.” Meanwhile, the science world was increasingly looking at oceanographic patterns within the full Gulf of Maine, revealing how local rivers, along with the world’s highest tides in the Bay of Fundy, oceanic currents, and George’s and Brown’s banks at the outer edge worked together to create a semi-enclosed sea. All these factors formed a remarkably nutrient-rich habitat for countless species of commercial and ecological importance. As a guide, I understood the value of giving people an opportunity to experience this place so they develop a personal connection. With this concept in mind, we loaded our kayaks on that Cape Cod beach and launched the Gulf of Maine Expedition.

RICH: Word of our plan got out and people approached with offers of assistance. Our vision to connect people to place was working. In addition to 24 community events spanning Provincetown, Mass., to Clark’s Harbour, N.S., we met countless people, each with a story of their own.

There were the people ashore at Egypt Beach, in Scituate, Mass., who jumped to action when a surf landing went awry for the tandem kayak in our fleet and the subsequent yardsale of paddling gear. There was the container ship captain responding to our VHF channel 16 securité call as we crossed the mouth of Casco Bay—at that moment I truly understood the power of this informational broadcast.

And there was the man and his son in a skiff crossing St. Mary’s Bay in Nova Scotia: when he spied us from more than a mile away, he changed his course 90 degrees to intercept us. He said he was a marine engineer, had been following us on CBC radio, and that we had changed the way he thinks about the Gulf of Maine. As an ornithologist, my conversations turned to the natural world. I learned storm-petrels are known throughout the Gulf of Maine as Carey’s chicks, black-crowned bight-herons are shitepokes, and our North Atlantic terns—common and Arctic—are mackerel gulls. Birds were omni-present. Every fishing boat trailed a veritable cloud of gulls feeding on fishermen’s discards. Fast forward to the 2020s and those clouds are now more like a light mist; gull numbers have decreased 40% over the past half century. Scientists are still assessing the causes of this decline but it seems to include factors that can largely be narrowed down to predation and climate change.

On the predation side, a consequence of our success restoring bald eagle populations is that their numbers have risen statewide from 40 pairs in the 1970s to more than 700 pairs today. Eagles need to eat and gulls are easy meals. One factor not much on our radar in 2002 was climate change. Warming seas change food types, abundance, and distribution. Rising seas put nesting colonies at greater risk of flooding. And increased storm severity can drown young birds on the nest. Climate change impacts not just birds, but every level of our natural and societal world, including fisheries.

NATALIE: Edging our kayaks close, we watched from outside the hanging nets of the heart-shaped herring weir. Three men and a teenage boy worked side-by-side from the edge of a skiff. They were bent over, hauling a net hand-over-hand into the boat. A school of herring (known as sardines once they are canned) was trapped inside the net and the fishermen were pursing the bottom shut to prevent any escapes. Weir fishing, adopted from the Wabanaki, was low-tech and highly effective, taking advantage of the natural movements of the fish.

The eldest fishermen looked up, caught sight of our group, and called us over. “Come on in!” We hesitated. A larger vessel, a sardine carrier, was also inside the weir, its vacuum pump poised to suction the catch into its hold. From the wheelhouse, the captain smiled and nodded kindly. The boy waved us in.

We maneuvered our kayaks through a growing sheen of fish scales and entered the weir by the same entrance as the herring. We soon learned this was the last active herring weir on Nova Scotia’s Digby Neck (once there were had been 33). The fishermen invited us in because, they said, “We want the world to know what we are losing.” For the first time in this family’s long line of fishermen, a father discouraged his son from planning a future in fishing. “We are likely the last,” he said.

Herring weirs once dotted most shores of the Gulf of Maine but few remain today. They have moved farther offshore where boats now target them for lobster bait. Continued herring decline has caused havoc in the lobster industry.

Serendipitously, Maine is seeing an upswing of pogies, another schooling fish which have helped fill in the bait void. Interestingly, back in 2002, we never saw the surface feeding frenzy typical of pogie schools coming through. Are warming waters triggering their return?

RICH: It was a sunny and calm July 2 as we paddled up the west side of Frenchman Bay to Bar Harbor’s low-tide bar. A handful of sandpipers worked the shoreline, feeding on invertebrates. These were early migrants, probably unsuccessful nesters and so got an early start on their southbound migration. Shorebird numbers have plummeted. Local birders tell of seeing shorebirds by the thousands in Bar Harbor during the 1970s. Today, we get excited to see four or five at a time on the low-tide bar.

On Aug. 11, we made our way to Mary’s Point, New Brunswick, adjacent to the Shepody National Wildlife Area, well up the Bay of Fundy. It was peak shorebird migration. The official count was 40,000. Compare this to a high of 200,000 semipalmated sandpipers reported in 1975. In 2022, the count never exceeded 12,000.

Climate change is not only causing decreases in wildlife populations, in many cases it is causing shifts. For instance, in Maine and New Brunswick, people are increasingly seeing tufted titmice and northern cardinals, both rare in 2002. And throughout the Gulf of Maine, sea turtles, giant ocean sunfish, and great white sharks are increasingly being seen.

NATALIE: I often think of an early morning paddle deep in the Bay of Fundy. Rich was waving frantically, pointing his paddle beyond my bow. I turned to look. A North Atlantic right whale surfaced with an audible woosh, barely a few paddle-lengths from our kayaks. It was unmistakable: V-shaped blow, enormous back, and most diagnostic, no dorsal fin. The animal’s presence rendered us speechless. It surfaced several more times, traveling for a few sacred moments alongside our kayaks. And then it was gone.

News was that Transport Canada would soon shift shipping lanes into St. John, New Brunswick, to protect the whales from ship-strikes. This region of the Bay of Fundy had long provided critical foraging habitat for the endangered right whales. The protections were a long time coming and applauded throughout the region.

Would we see right whales in the Bay of Fundy today? The answer is quite probably no. The whales appear to be eschewing the bay for waters farther north in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Scientists think the warming of the Gulf of Maine has triggered substantial changes to the food-web, including the northward shift of Calanus, a type of zooplankton that right whales rely on for prey. I wonder about the weir fisherman’s son; did he heed his father’s recommendation to seek a profession other than fishing? Or is he finding ways to adapt to change? For example, fishermen in the southern Gulf of Maine are seeing more black sea bass, a fish of warmer waters. And northern shrimp, true to their name, are venturing even farther north while longfin squid, traditionally more abundant farther south, are on the rise. What will be different the next time we travel this route? Changes in the Gulf of Maine are complex and understanding them requires everything from in-depth scientific research to the stories from people who live and work here. For us, it was time spent at sea that offered us immersion in the elements with ample time for observation, taking a snapshot of the way things were in 2002. That, and the stories of the people of this place and their ways of connecting with the sea, will help us develop a new and ever-evolving picture of the Gulf of Maine in the future.

Natalie Springuel and Rich MacDonald live in Bar Harbor.