“A poet, more likely than not, has to take his local identity for granted. If he feels he is ‘from away,’ he will be. If he is too much concerned about where he comes from or where he is, what he makes of the relation between himself and his part of the world will seldom sound or feel right.”

So did Samuel French Morse muse in his introduction to a group of his poems in the anthology Maine Lines: 101 Contemporary Poems about Maine, 1970, compiled by Richard Aldridge. Morse concluded: “As a New Englander by birth and temperament, I could hardly think otherwise.”

In introducing his first book of poems, Time of Year, published in 1943 in the middle of World War II, poet Wallace Stevens picked up on that New England spirit in Morse’s writings: “He is a realist,” Stevens wrote. “He tries to get at New England experience, at New England past and present, at New England foxes and snow and thunderheads.”

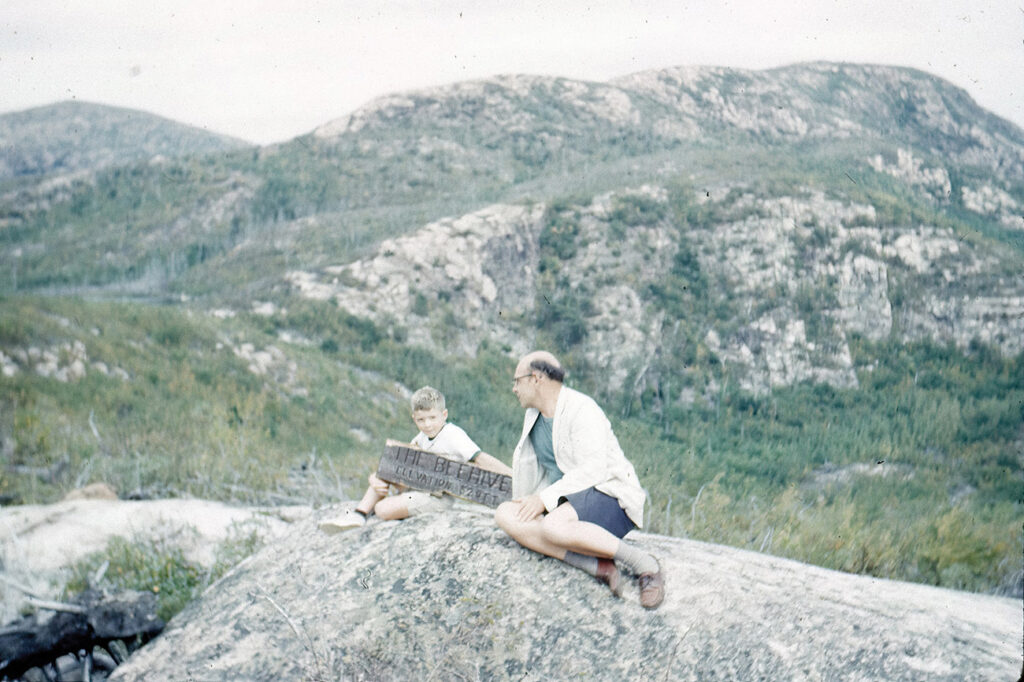

We can add Maine islands to that list. Spending summers on Hancock Point, just northeast of Acadia, Morse and his family went on sailing trips among the isles of the Downeast archipelago, voyages that inspired some of his finest poetry.

Two poems in particular, “A Trip Outside” and “The Islands in Summer,” reflect Morse’s passion for seafaring. In each poem, which are among his longest, he takes us on a tour by boat of greater Frenchman Bay.

“Our voyaging is local by the chart” is how “A Trip Outside” begins, after which Morse provides the itinerary. The poem’s progress resembles tacking as we move from line to line via brisk enjambments:

Past Scylla, white with gulls, that changes least

Of all the landmarks we have grown to know,

Past Jordan’s Cove, past Swan’s, against the slow

Uneasy swells the August trades bring in

On a good day.

The family lands on an island which they explore from end to end. “We skipped a hundred stones / Toward Ironbound and Stave,” the poet recounts, “proud as castaways…from some dead ship.”

Some of the same landmarks appear in “The Islands in Summer.” Here Morse compares the scattered isles to “a kind of constellation.” He offers a partial list: “Ironbound, Jordan, Yellow, Heron, Stave, / Calf, Preble, Dram….” Imagining rowing from Hancock Point to Stave and back, he would listen and look for landmarks:

The bell off Crabtree Ledge would toll me on

When I got past the Broads, but one bright mark

Could hold me all the way, if it was clear:

The very star would do as well, that shone

On Sieur de Monts the night he landed here.

Other islands appear elsewhere in Morse’s verse. Part XIX of “A Handful of Beach Glass” evokes Great Wass. In just four lines the poet offers an evocative snapshot of a special anchorage while providing the correct Downeast pronunciation of “weirs.”

Nobody fishes here; and where you go

to watch the shorebirds when the tide is low,

the summer seems as idle as the airs

running like herring through the ruined weirs.

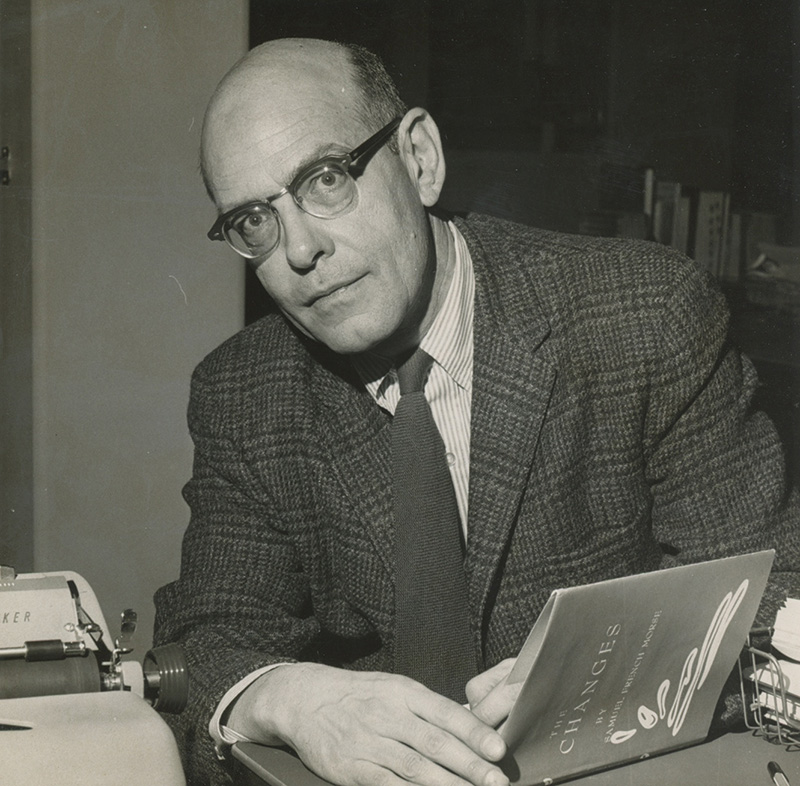

In his introduction to Morse’s Collected Poems, published by the National Poetry Foundation in 1995, Guy Rotella explains how the Salem, Mass.-born writer came from an “old New England line connected to the Salem Pickerings and, he thought, to the Coffins of Nantucket.”

Morse once recounted that he had had access to Salem’s Peabody Museum “at all hours” as a child, an opportunity that may have helped make him, writes Rotella, “the observer, collector, and namer he became.”

Morse graduated from Dartmouth in 1936 with an A.B., then went on to Harvard for an MA and Boston University for his Ph.D. A distinguished teaching career included stints at Harvard, Colby College, University of Maine, Trinity, Mount Holyoke, and Northeastern, the last the longest of tenures, from 1962 to the 1980s. The Northeastern University Press awarded the Samuel French Morse Poetry Prize in his honor from 1983 to 2009. He also gained acclaim as an authority on the poetry of Wallace Stevens.

Some years ago a former student at Northeastern, Marc Widershein (1944-2016), offered an admiring tribute (available online as “The Changes: A Memoir of Samuel French Morse”). He describes meeting with the poet in the university cafeteria for critiques. Morse suggested that Widershein read C. S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters and remarked at one point, “If you can get up in the morning, look in the mirror and not get depressed, you know you have grown up.”

Two of Morse’s poems, “A Poem About the Red Paint People” and “Micmac,” appear in the landmark anthology Maine Speaks, published by the Maine Writers and Publishers Alliance in 1989. The editor’s note recounts that when the poet lived in Maine, “his home was at Hancock Point.”

[Morse] was there enough to keep a garden, and in it, some unusual plants not native to Maine. He liked to tell their names, and where they’d come from, which adventurer had brought them back, which nursery stocked them. He liked just as well, while walking visitors around the point, to name and place the natives—plants and birds, the islands—in Frenchman Bay. Not born in Maine, he knew the word “native” meant different things, including the mysterious Red Paint People, long extinct, and the Micmacs, who persist.

That Downeast promontory was Morse’s north star. His inscription to his friends Francis and Sidney Hamabe on the flyleaf of his book Changes, 1964, reads “To Frank and Syd, who know better than almost anyone else, the place ‘where I ought to be’ really is the other side of the point.”

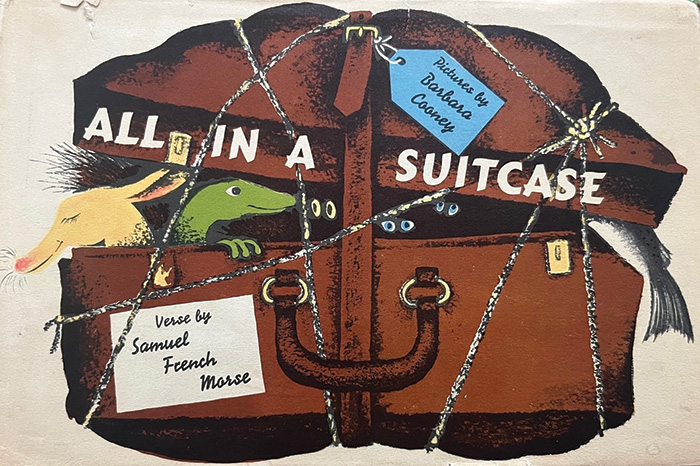

In his children’s book All in a Suitcase, 1966, illustrated by Barbara Cooney, Morse offers an animal alphabet in rhyme based on the “I’m going on a vacation” memorization game used to entertain kids on a long car ride. His wife, Jane, who was an authority on Beatrix Potter, helped with the text. While the journey in the book ends in Boston, the version that appears in Morse’s Collected Poems winds up—yes—in Hancock Point.

Morse, his wife, and their son Sam make a number of appearances in Sanford Phippen’s comprehensive two-volume The Sun Never Sets on Hancock Point: An Informal History published in 2000. The family contributed to the spirit of this special enclave, serving on various community committees, and giving readings and talks.

Samuel Morse, Jr., Mitchell Professor of the History of Art and Asian Languages and Civilizations at Amherst College, remembers his father as someone who loved nature. He likened his father’s perspective to that of Chinese painter Dong Qichang (1555-1636), in particular an album of paintings titled “Within Small, See Large.” His father “would rejoice in the beauty of a cardinal flower that he saw on a hike, or the call of a black-throated green warbler.” What was special, the son recalls “was that he was always then turning those experiences into poems.”