“It could cut the heart out of a man to think too much about what he was working for.”

—Michael Crummey, Hard Light

To call the life of Newfoundland outport fishing families tough would be a gross understatement. Never mind the incessant wind, the seas, the weather, the sleet, and the bony land that was difficult to farm; they were also caught in an economic system that allowed almost no escape.

The coin of the realm from the 16th century onward was salt cod, which was the only product the families had to trade. But the people themselves had little to say about the value of their fish or the cost of necessities.

Newfoundlanders were employed in the merchant “truck” system. Fishermen were required to fish for and buy their kits and household needs for the year from the merchant companies. Families were so poor in some cases they couldn’t purchase their own hooks to fish for themselves. Women and children were the beach laborers in the grueling work of “makin’ the fish” well into the 20th century.

One fisherman said about the inshore salt cod operation in the 19th and early 20th centuries, “We’s catches ‘em and the womens makes’em.” The skill of turning whole fish into salt cod in the barrel was key to the quality of the finished product’s grade and the price paid to the fishermen.

An industry broadside from the 1850s, “Grades & Classifications of Salt Fish,” describe the characteristics of 24 different grades.

There were variations along the coasts on the exact way to make the best grades, but the basics always were gutted and headed cod, salt, time, and wooden barrels that held a quintal—112 pounds. After the filets soaked in brine for five to seven days, each was laid out in the morning, flat on cobble beaches or raised platforms built of cut saplings, then stacked into a pile at evening.

As one woman in the oral history, Strong as the Ocean: Women’s Work in the Newfoundland and Labrador Fisheries described it: “When [the pile] got so high, we used to make it up almost like a sharp roof, like a peak on a house. This was a real art and had to be done just right, or it didn’t suit.”

When the weather threatened, they were piled up again and laid out afterward. Drying could take weeks. The hardened fish was stacked, filet by filet, into the barrel. Once sealed into the barrel, the salted fish stayed good, even in the tropics.

A finished lot of processed fish was then graded by the merchant’s fish buyer, usually at the end of the season. It was then the family debt from that year was paid off and what was left could be used to buy flour, lard, clothing maybe, candle wax, and all they needed until the spring when the cycle started again.

As another woman commented: “In the morning sometimes I sat on the bed and me legs be that still and tired, I could hardly get me stockings on.”

The fishermen didn’t fare any better. “Water pups” were the bane of hauling lines in and pulling fish up year-round—a painful string of blisters around the wrist chafing from constant salt water. Newfoundland poet Mary Dalton describes it as “[t]o burn with the fire of water pups.”

It was into this environment that the Fishermen’s Protective Union was initiated by Newfoundland businessman William Ford Coaker. He recognized that the system meant fishermen had no direct access to markets or control over prices.

This state of affairs was a major barrier to improving not only the standard of living for fishing families and their communities, but also to the economic well-being of all of Newfoundland and Labrador. At this time, cod exports were still the backbone of the island’s economy and much of this product was being produced in the outports, small coastal villages accessible only by sea.

On Nov. 3, 1908, Coaker delivered an hour-long speech at Orange Hall in Herring Neck arguing for the formation of a fishermen’s union. He was promoting a more equitable system to spread the great wealth of the fisheries to the common fisherman. He asked those who were interested to stay behind to talk about it and 19 did.

By 1909, 50 local councils had joined with 1,200 members. Five years later, the Union boasted 21,000 members in 296 councils—over half of the island’s fishermen.

It became the British colony’s most dynamic social, economic, and political force. The Union’s rallying cry, “To Each His Own,” was based on the conviction that Newfoundland’s outport “toilers” needed to have more of the profit on the fish they produced.

The union operated on three fronts: Foremost was acting as a cooperative for selling the catch to have some say on the grading and pricing. But that wasn’t the whole problem; they also needed to circumvent the inflated pricing by the St. John’s merchants on their gear and household items they needed.

To that goal, they set up the Fishermen’s Union Trading Co. (UTC) and established stores throughout the province which would not only purchase fish from fishermen for cash but would also bring in goods to sell to fishermen directly.

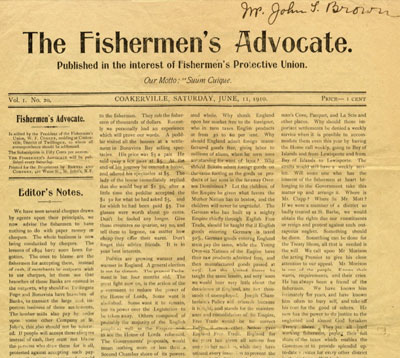

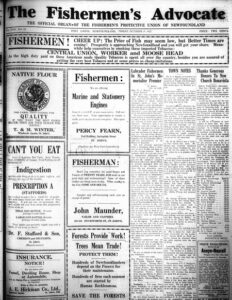

The FPU also recognized the need to inform and educate the fishermen on what was happening in the various villages and the wider world.

To this end, they established the newspaper The Fishermen’s Advocate, published in Port Union, which was called the “only union-built town in the province,” meaning the new fishing port was purpose-built by union labor. The paper was published in both daily and weekly editions from 1914 to 1924.

They soon recognized there was political arm needed to be heard in government and The Union Political party was formed. The so-called Bonavista Platform included items such as schools for every settlement with over 20 children, and subsidies for steamers bringing coal to outports. At the top of the list was standardization and transparency in fish standards and pricing.

Coaker stepped down as union president in 1926 to focus on FPU’s commercial activities. Many FPU companies had long-term success. According to the Canadian Atlantic Business magazine, the Union Electric Light and Power Company operated until 1967 when it merged with other utilities to form Newfoundland Light and Power.

“The union slowly faded away after its final annual convention in 1939,” the magazine notes. “However, as the first organization of its kind, its impact on Newfoundland’s fishery cannot be denied. Today, Port Union and many FPU buildings are designated historical sites. [Over a hundred] years later, ripples of influence remain.”

Linda Buckmaster has lived in Waldo County for 50 years. Her most recent book, Elemental: A Miscellany of Salt Cod and Islands, was a finalist in the Maine Literary Awards. Her traveling literary exhibit, “Of Cod and Communities,” toured Maine coastal libraries. She is currently working on a novel set in late 19th century Newfoundland.