In the later stages of my father’s life, dementia slowly exacted its toll while the long-tail effects of a stroke increasingly limited his mobility. Still, my father daily summoned his strength and focus to move from the living room to his kitchen table chair—an often slow, nail-biting, yet inspiring trek. He usually sized up his next move, extended his arm, and lunged from door casing to countertop to chair back. When he finally dropped down in his seat, his lips creased into a smile and his tired eyes sparkled once more.

“Made it,” he would proclaim to no one and everyone.

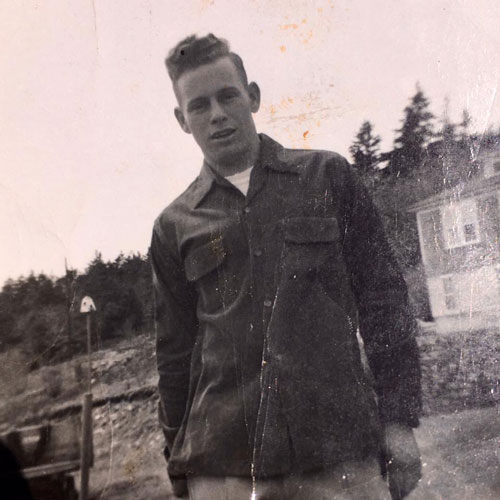

Following the death in January of my 86-year-old father and coastal icon, David Lunt, I read many lovely notes from friends. Many mentioned his knowing smile or his eyes. When reading a man who accomplished so much, but held his cards so close, such features spoke volumes in a flash—comforting, confident, knowing, sly, trust—the answer key to a poker face. I knew them well.

The sweeping story of my father’s life is remarkable, layered, and endlessly fascinating. He was a lifelong fisherman, businessman, and community leader born in the remote island fishing village of Frenchboro when it still lacked basic amenities such as electricity and indoor plumbing.

Like so many islanders, his parents, Sanford “Dick” Lunt and Vivian (Davis) Lunt, grew up in poverty. He married Avis Sandra Morris in 1958, built an island home, and raised three children on the banks of Lunt Harbor.

He was blessed with a sharp mind and operated on instinct (he was not fond of “process”) to help pull his hometown into a more modern world. And he worked tirelessly with state agencies and organizations, such as Island Institute, to push new ideas in a constant struggle to keep it alive.

He was guided by tradition, but unafraid of change; a six-generation native with roots running deep into island soil, but an adventurer at heart. Throughout successes and failures and joys and hardships, he remained unflappable, rarely raising his voice, and never flashing anger.

Good writing should include a narrative arc, a connective thread that binds a larger story—for a half century my father served as lead protagonist for his community and as my throughline and inspiration. He was a calming presence who sowed confidence and trust despite never actually verbalizing it. Instead, his parental superpowers fired in those eyes and danced on those lips. From Little League through college and into adulthood, he never said much in my moments of joy or pain or confusion, but his face and his smile and his body language told me it would be alright.

During a cold wet spring in 1984, he drove me across the New York Thruway to the gray and seemingly dying industrial city of Syracuse. We stayed in a way-past-its-prime downtown hotel that hugged deserted city streets sitting somewhere between quiet and dangerous.

Up the hill, the Syracuse University campus pulsated with more than 10,000 students, imposing academic buildings, and the cavernous 50,000-seat Carrier Dome. We were not on Frenchboro anymore.

My dad took it all in, as he always did, never offering an opinion about whether I should enroll. He knew I needed to make the decision. Some, including my mom, felt I shouldn’t go. When I officially mailed my acceptance letter, Mom was shocked.

Dad just signed the paperwork, telling Mom, “He knows what he’s doing.”

She would fire back, “What if he doesn’t?”

He’d just shrug and say, “He’ll just try something else.”

And that never changed. Dad never gave me a single piece of this-is-what-you-must-do advice in my life, rather he spent a life instilling confidence and trusting that he was mentally handing over a DIY inner voice to guide me.

Later that fall, when he dropped me off at Syracuse, he stood on the sidewalk outside my dorm, with a twinkle in his eyes and a wry smile as if to say, “I know you got this and you know you got this.”

Jump ahead 35 years, and we were on a different highway in a truck camper heading south. Neither of my parents could make such a drive anymore, so I was taking them to South Carolina to set up their campsite. I took care of the details, including finding a local locksmith to cut extra keys and map out spots to hide them for the sure-to-happen lockouts.

My mother scoffed, but Dad, ever the pragmatist, understood it was all necessary so he could enjoy his final Carolina sunsets. He followed me everywhere, watching what I did and how I did it.

Finally, when it was time for me to head back to Maine, Mom was sitting at the picnic table fretting whether they could handle everything. Not Dad. He was just standing there as if to say, I got this and you know I got this. I drove off and didn’t doubt it for a second; those eyes and that smile told me so.