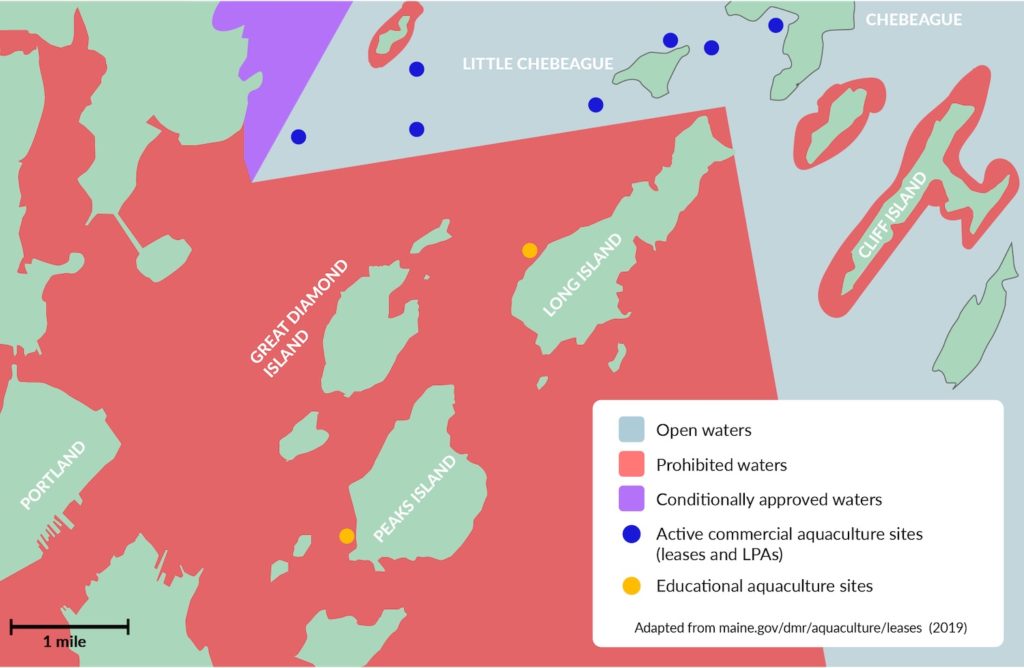

Commercial aquaculture, a source of income for an increasing number of coastal Mainers as a means to bolster their marine livelihoods, is not possible unless the waters one plans to farm in are designated as suitable for shellfish harvest by the Department of Marine Resources (DMR). Zones that have not been tested are classified as closed to aquaculture because it is unknown if shellfish grown there would be safe to eat. The trouble is, many of those closed zones are are suitable for shellfish harvest, but there isn’t always the capacity to obtain the survey results to prove their safety. Routine water quality testing can be a complicated process, and those complications only worsen when the zone in question is off the shore of an island.

The community of Long Island, a Casco Bay Island about forty minutes away from the mainland by Casco Bay Lines, got involved with aquaculture through educational programming. Marci Train, Long Island’s grade 3-5 schoolteacher, spearheaded the island’s original aquaculture efforts. Listen to an excerpt of her presentation at Waypoints 2019 in which she explains the impetus for water quality testing in the waters surrounding Long Island and the links the project had to education and her students.

HOW IT WORKED

Marci Train saw a problem, and instead of asking herself why the problem existed, she asked herself what she needed to do to fix it and what resources did she have to work with?

The waters surrounding her island were closed to commercial shellfish aquaculture. The students could grow kelp, which doesn’t take in toxins and bacteria like a filter feeding bivalve, but the kelp could not be brought to market due to perception concerns associated with seaweeds grown in closed areas. To reclassify a growing area, the DMR requires years of monthly testing in order to be confirmed as safe harvest shellfish, and Long Island students were expressing a sincere interest in aquaculture as a career. Marci met with DMR and local stakeholders and was encouraged her to gather volunteers to expedite the sampling process.

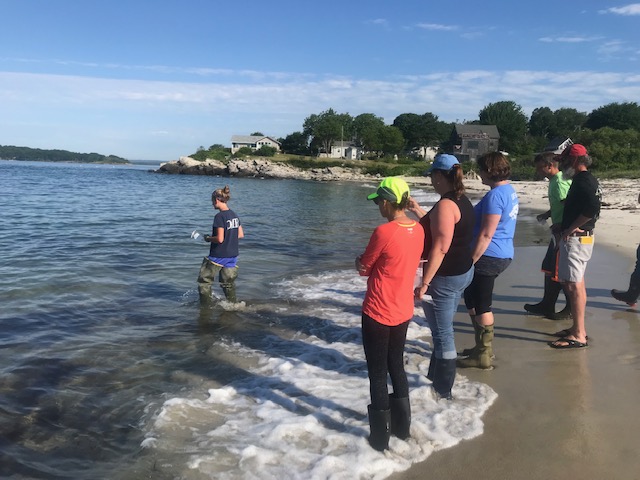

Her students had already gotten the community excited about growing kelp, so Marci made a pitch at a community potluck. She asked parents and community members to join a team of volunteers who would be trained and certified to retrieve water samples for DMR to test. She used the school news and the local newspaper to spread the word about her team of water testers and how to join. Fortunately, word got around, and she assembled a team to work with.

CHALLENGES

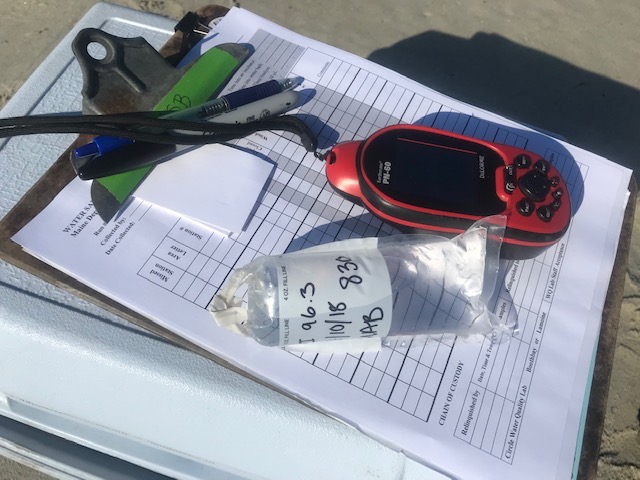

Marci recalls the three essentials to overcoming the logistical challenges involved with water quality testing on a Maine island: determination, drive, and cheerleading. The team of about nine committed volunteers were all citizen scientists who needed to undergo training. There were permission slips and tests that needed to be filled out before a volunteer could be certified to handle the samples. Even the person taking it from the ferry to the mainland had to be certified. Reportedly, the test wasn’t very easy either. Marci coordinated the efforts and made sure her team filled out their paperwork. Even after the DMR sent a professional out to train the team on how to take samples, there were still other complications to consider.

One issue was ensuring access to testing sites. There were certain sites that needed to be confirmed by private landowners. It was possible that landowners could have had hesitations about participating, but in the case of Long Island, no objections were raised.

Another challenge is maintaining consistent contact with both the volunteer team and someone at DMR. The process is unlikely to be successful if it relies upon one person. Since Marci had responsibilities as a teacher, there were many days she couldn’t gather the sample, and she leaned on the support of her team. Communication with DMR regarding the process was vital because a DMR representative visited the island for hands-on training and supplied the team with everything they needed to retrieve and transport samples including the icepacks, a cooler, and a thermometer.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

This approach to water testing is entirely based on volunteerism. No one on the island collecting water samples receives compensation.

While the lobster fishery is currently a reliable source of income, Maine’s fisheries have the potential to be in flux, which means that marine livelihoods may look different in the coming decades. Marci Train attributed the success she’s had so far to the education of the community about why opening Long Island’s waters to aquaculture was in the best interest of the island’s future.

At this time, there are commercial aquaculture sites near Little Chebeague Island less than a mile offshore Long Island’s northern coast. Residents of Long Island operate aquaculture sites in this neighboring zone which has been classified as safe for commercial aquaculture.

The team of volunteers have another year (as of 2019) of gathering and delivering samples until the zone in question can be reclassified.

RESOURCES

- DMR’s Interactive Map shows active leases and LPAs as well as closures and prohibited waters.

- Water Quality Monitoring Forms and Protocols

Originally Published November 2019