PHOTOS BY AMY WILTON

Painter Greg Mort has a compelling case in asserting that art and science are complementary, not conflicting realms. Mort, who has been fascinated and inspired by astronomy and space exploration since he was a child, invokes the now-famous photograph of Earth, taken from Apollo 8, an image that revealed the planet in a surprisingly diminutive context and, perhaps also surprisingly, mostly blue in color.

“It’s really a blue marble,” he remembers thinking, and the image became a beautiful way to understand the elements of the universe.

Mort holds that perspective close as he considers the world that he paints. In fact, he carries a card with him that, when held at arm’s length, shows the size of the moon as it would appear in the night sky to the naked eye, and also includes a shape that represents the size of the Earth as it would appear to someone standing on the moon.

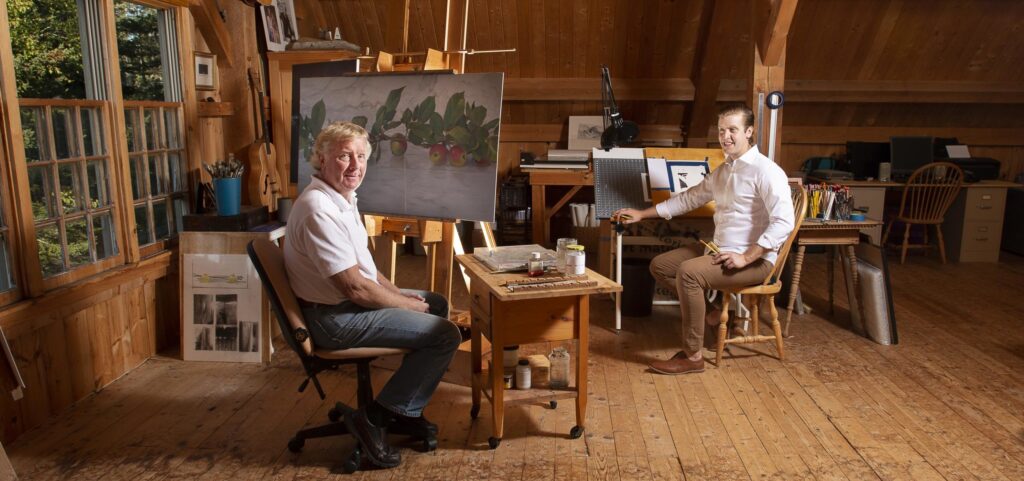

But both Greg Mort, 68 and his son and fellow artist, Jon, 35, whose work evokes the universe’s powerful, dynamic forces, are very much inspired by Maine. For 40 years, the senior Mort has summered in Maine. He’s painted in a post-and-beam barn and hosted an open studio in Port Clyde. Jon continues the 40-year tradition of welcoming visitors to the barn for the annual event the first weekend each August. Greg lives the rest of the year in Ashton, Maryland, and Jon lives in Washington, D.C.

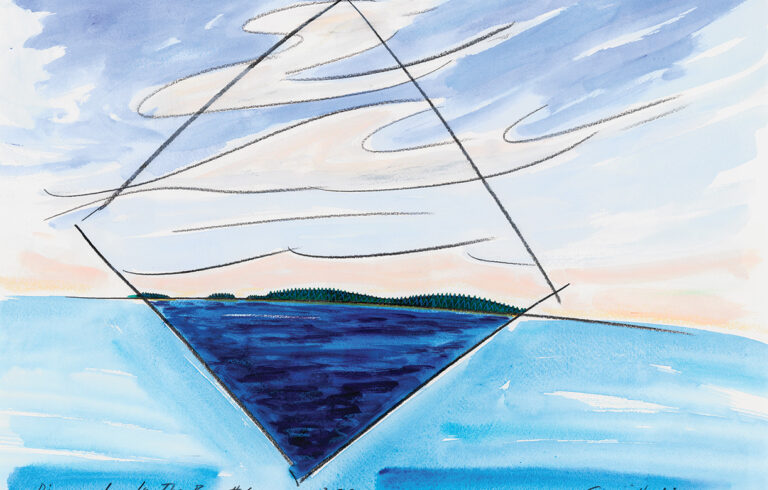

And it’s not just the state, but in particular, Maine’s islands that fill their vision.

“Maine was the main inspiration for my art,” Greg says. “It is physically beautiful.” And on islands, especially, a raw quality emerges. “The ocean puts a patina on everything,” he says. An uninhabited island “looks as it has for thousands of years. The pure beauty of nature” is on display, he explains.

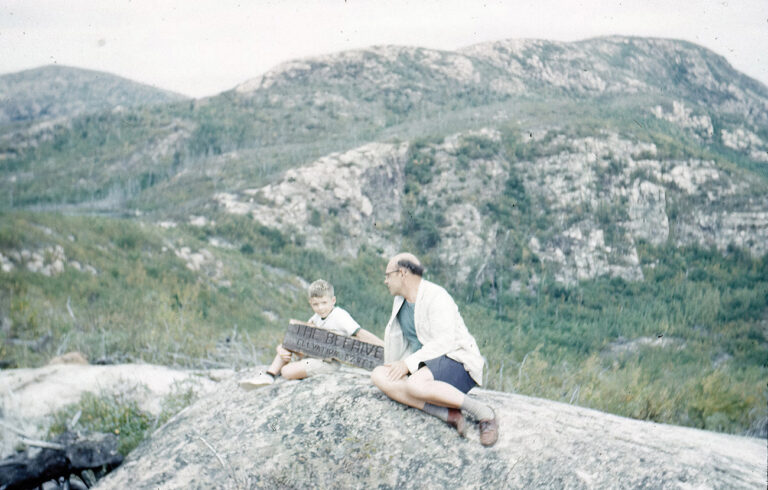

Greg Mort marks his beginning as a professional artist in 1977, about the same time he was invited to visit the state by the woman who introduced his work to the Washington, D.C. area. She had a farm near Tenants Harbor, and when Mort visited, he was smitten. Ten years later, he and his wife purchased Fieldstone Castle—an architecturally striking house literally made from fieldstones, completed in 1914—where they live through the summer months.

Returning each June is a ritual like a warm embrace from a friend.

“You look around to see what’s changed, and it’s usually nothing,” he says with a chuckle. “Maybe somebody painted their house.” That constancy is appealing, he says. So are the relationships he’s developed over the years with visitors to the barn workspace in what he terms “a 40-year time-lapse of friendship.”

The fieldstone house itself is another touchstone for his art and passion, for it was designed and built by Russell Porter (1871-1949), one of several in the area. Porter is renowned as the father of amateur astronomy, of which Mort is a passionate acolyte. He and his wife purchased Fieldstone Castle because of Mort’s interest in Porter, who also was an artist. Porter traveled above the Arctic Circle nine times, Mort notes.

He remembers a childhood friend who had a telescope. “We looked at the moon, and I just thought, ‘Wow!’ I followed the Soviet and U.S. space programs very carefully,” he says, and after establishing himself as an artist, he was able to meet some of the Apollo astronauts, including Neil Armstrong, who was presented with one of Mort’s works.

And he keeps an eye on the sky, despite it being increasingly difficult to see much.

“That’s one of the things that’s so precious about Maine—what the astronomers call ‘dark skies,’” he said. “Maine is way ahead of the curve in terms of making a change.”

He is active in the movement urging policy makers to consider using fewer street lights, and shading those that are used. He is a member of the International Dark Sky Association, and has donated art to the cause. Darkness, he said, is “actually the real state of affairs,” as the stars and moon emerge. “The curtain’s closed in the day time,” he adds. And 80 percent of the organisms in the world are nocturnal, further suggesting that night is worthy of the artist’s attention.

“The ocean puts a patina on everything.” An uninhabited island “looks as it has for thousands of years.”

—Greg Mort

Islands, like the night sky and its stars and moon, hold a degree of mystery. And they hold a universal appeal. “People understand and long for it,” Mort says, in part because these bodies of land surrounded by water “are a whole different entity.”

The Brothers, two small islands that become one at low tide, and Hupper Island, off Port Clyde, are favorite haunts.

The Brothers, two small islands that become one at low tide, and Hupper Island, off Port Clyde, are favorite haunts.

The Brothers “has this lovely spruce tree on it. You can see it from the mainland.” The tree has become an icon, a touchstone of sorts to him, and more. “I guess it’s one of these little obsessions,” Mort admits, and it has figured in several paintings. “I’ve painted it from any number of angles.”

Mort’s work reflects all of the above—a love of the Maine coast and islands, an awe of larger forces and small emblems that shape and fill them, and the light that is found only on these shores.

“I’m really intrigued with the relationships between things that are very big and things that are very small,” he explains, “the realms of large and small,” and indeed, his work includes both, like a piece that features a close-up view of shells on a beach as the Milky Way rises.

“The bulk of my work over the years has been watercolors.” He likes how colors can be layered, and yet retain an element of transparency, “letting it do what it wants to do, and yet control it.” And “the portability” of the medium allows him to be out in the natural world.

Mort’s work has been compared to that of 17th century Dutch painters like Vermeer, but he sees his work more in the tradition of the 19th and 20th century luminous painters, such as Frederick Church, George Bellows—who worked on Monhegan—and Rockwell Kent.

“They were naturalist painters,” he says, singling out Kent, who “was able to capture that understated beauty” of the natural world.

Mort’s work is, in some ways, minimalist, despite the scope, and it is precise. It reflects, he says, “a love of the craft of painting, this reverence for the object.”

The paintings seem like still-lifes, despite the galactic sources.

Greg’s son Jon Mort seems to have taken up his father’s passion for understanding the universe’s workings and gone even deeper. Like his father, the younger Mort’s work might be described as still lifes, but the elements he gathers and depicts speak of both the natural and human-made worlds.

Mort’s work has been compared to that of 17th century Dutch painters like Vermeer, but he sees his work more in the tradition of the 19th and 20th century luminous painters, such as Frederick Church, George Bellows—who worked on Monhegan—and Rockwell Kent.

“They were naturalist painters,” he says, singling out Kent, who “was able to capture that understated beauty” of the natural world.

Mort’s work is, in some ways, minimalist, despite the scope, and it is precise. It reflects, he says, “a love of the craft of painting, this reverence for the object.”

The paintings seem like still-lifes, despite the galactic sources.

Greg’s son Jon Mort seems to have taken up his father’s passion for understanding the universe’s workings and gone even deeper. Like his father, the younger Mort’s work might be described as still lifes, but the elements he gathers and depicts speak of both the natural and human-made worlds.

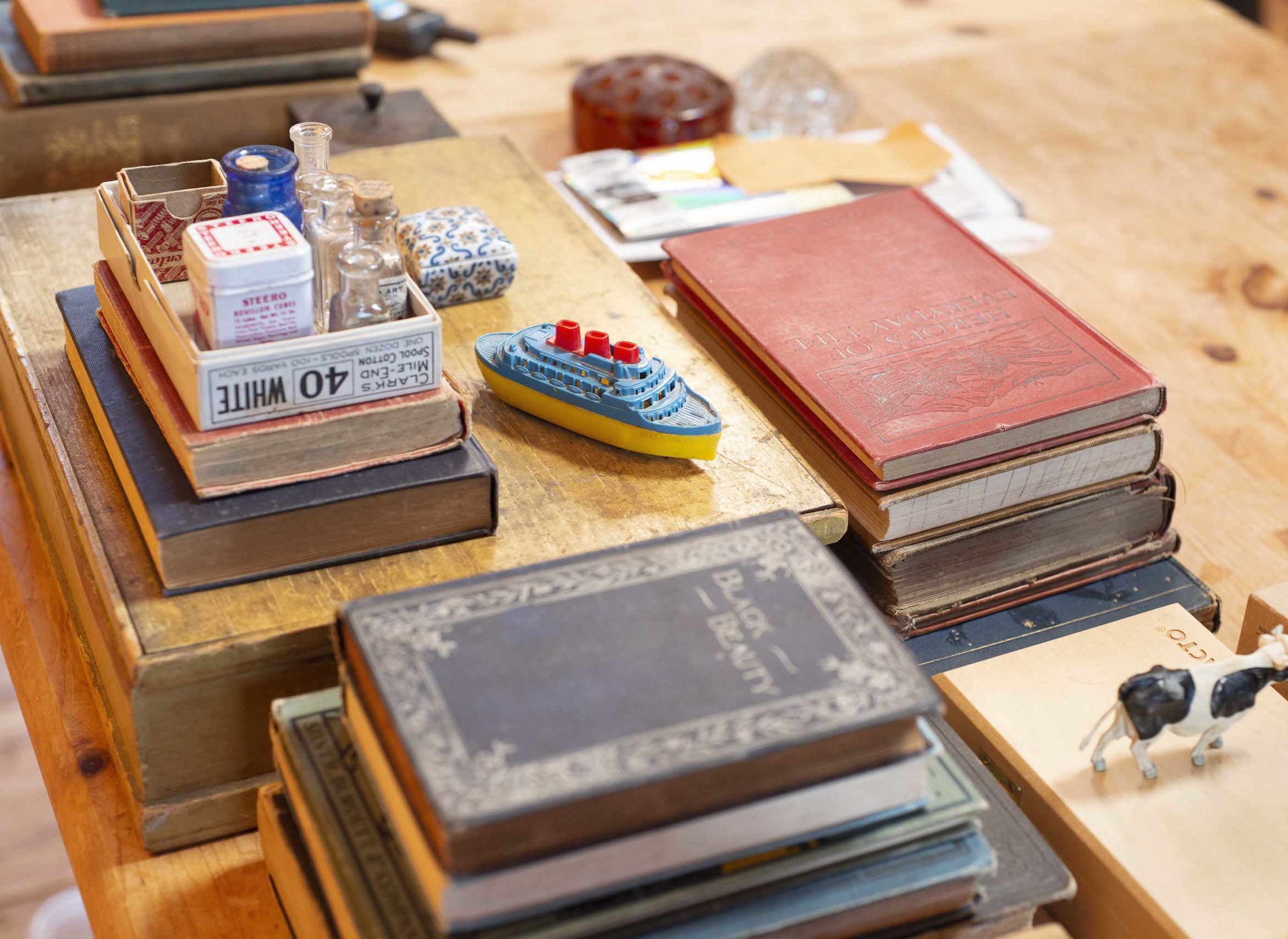

“Heaven Trembling” includes sand dollar and periwinkle shells; a wooden frame; a model of a space capsule; and calipers, suggesting the artist is asking us to measure these elements. Mort says that, “In the end, the work is about storytelling.”

“Art is the true daughter of science.”

—Jon Mort

“It is the endless story of the tides,” he explains. “Watching them, it’s like you can feel the world turning. As a child, some of my most vivid memories are wading into a tidal pool, watching the minnows and crabs hiding.”

Another work combines shells, the bottom of a small, square tin, and stamps. The origins of each have personal connections, and, as arranged, are pleasing to the eye, but for Mort, they also speak of civil discourse, and the “aspirationally egalitarian society” in which we live. “The shells are from all over and facing in different directions,” he notes.

In addition to the still-lifes, Jon’s work includes the human figure and the landscape. “Maine holds a lifetime of inspiration,” he says.

“I credit this place for my deep appreciation for the natural world,” he continues. Inspiration is all around. “I’ll see a beautiful red squirrel, its copper colored coat, whales passing the boat on the way to Monhegan…” he says. The world here provides “an awfully wide window to look through.”

Observation runs deep in both science and art, Mort says, and seeing leads to reverence. “Art is the true daughter of science. You don’t seek to change anything—you only seek to comprehend.”