ILLUSTRATIONS BY SCOTT NASH

Elias and Drew donned the life jackets they’d selected from the wide assortment found in the barn and scurried out onto the line of rocks and ledges that constituted a little jetty at the head of the rapids. Twelve-year-old Elias had been coming to Vinalhaven from Illinois with his folks for a dozen summers, but his friend Drew, also twelve, was enjoying his first trip. For that matter, it was Drew’s first solo trip of any consequence outside Chicago, where he lived with his folks and went to school.

Elias’s family rented a saltwater farm on seven gently rolling and magnificent acres that fronted on the southeast shore of Vinal Cove. The big, comfortable farmhouse and nearby barn sat naturally on a modest rise overlooking the cove. Once an active saltwater farm, it’s now a pastoral retreat enjoyed not only by the appreciative seasonal owners and their guests, but also by the islanders, to whom those owners have graciously extended permission for such things as a fall carnival, musical events, auctions, fund-raisers, and so forth.

For years, too, the picturesque farm has been the first choice of many a celebrant, newlyweds in particular. Photos of brides and grooms gazing adoringly at one another under an arbor facing west toward the cove, or north over the rolling little meadows, or in the big timber-frame barn after an indoor ceremony are scattered far and wide around the country.

The boys shared a bedroom on the second floor of the big rambling farmhouse, and the enchanting scent that saltwater ways dispense now and then breathed wakefulness into them each early morning, fueling their enthusiasm for what each new day might offer. Sounds of competing gulls amplified the anticipation, particularly if the tide was out and the flats exposed.

If the tide was not fully out, but on its way, the gulls and terns would be diving in and out up at the rapids, at the north end of the property where Vinal Cove quenches its thirst twice a day with each incoming tide, having expelled an identical quantity just a few hours earlier. At this restricted waterway between the cove and Winter Harbor, its patron estuary, the outgoing tide creates substantial rapids—fairly clear of rocks and obstacles—extending downstream for a hundred yards or so.

During this vacation the boys had been converging at this juncture to ride the rapids nearly every day, about two hours after high tide had turned. Then, for several exciting hours, the water was moving at full force but afforded enough depth to allow them to avoid the rocks beneath.

Of course, the outgoing tide was simultaneously rolling seaward in Winter Harbor, and its water level was dropping, too, so riding the rapids too long after the tide had turned would not have provided enough depth for the safe passage of two boys hurtling gleefully downstream.

On one of those days the boys headed for the rapids at about noon, with Elias’s watchful mom, as always, observing from shore. Their arrival coincided with a carnal frenzy of some tiny critters, maybe herring, out in the harbor just beyond the rapids. Whatever that critter was, its activity attracted a handful of predators not far from the rapids, but far from the trio’s attention. While Elias’s mom urged caution from the sidelines—though less urgently with each passing day, since there’d been no mishaps or injuries—the boys scrambled toward their chosen launching spot. This was routine now—no lingering apprehension—and Elias flung himself confidently into the rushing water.

While Elias’s mom urged caution from the sidelines—though less urgently with each passing day, since there’d been no mishaps or injuries—the boys scrambled toward their chosen launching spot. This was routine now—no lingering apprehension—and Elias flung himself confidently into the rushing water.

As soon as the current jerked him around so he faced downstream, he sensed an extraordinary, startling, and unexpected warmth underwater next to his right side. Glancing down he could easily make out a large shadow, much larger than himself, nearly touching—and then touching—his leg.

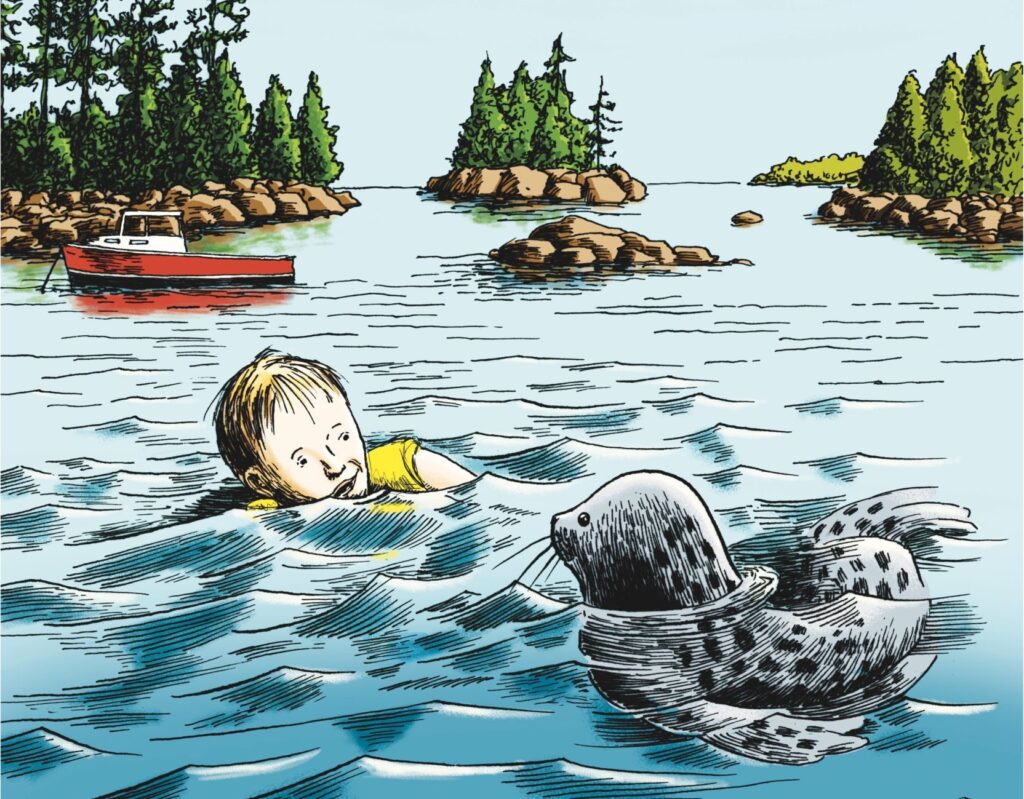

His first thought—not surpri-singly for a twelve-year-old boy—was that it was a shark or some other underwater monster, but just as quickly he deduced—also remarkable for a twelve-year-old—that given the distance from deep water and the shark’s customary habitat, this was unlikely.In the next instant, a big harbor seal popped up right in front of him; its steely black head, much bigger than his own, had white stripes extending from the center of its forehead down and off to the right and left, on either side of its V-shaped nostrils. These were contracting and expanding, the latter effort enveloping Elias’s face with a pungent odor, not altogether unpleasant but unmistakably digestive.

The big creature’s eyes looked inquiringly into Elias’s own as the duo hurtled down the rapids—Elias facing downstream and the seal facing upstream—their heads about a foot apart, perfectly choreographed. The ride

seemed to go on forever, Elias at the mercy of the current, exercising no control whatsoever, and the seal entirely otherwise, effortlessly making adjustments where necessary to keep it facing backwards.

This business of keeping its bulk a foot away from and facing the boy for the duration of the tumultuous ride presented no challenge to the playful pinniped. Watching from shore, aghast at first, Elias’s mom saw the astonishment and wonder on her son’s face as this miraculous adventure unfolded, and began running parallel along the shore, the better to rendezvous with him the instant the ride was over.

The thrill lasted nearly a minute, one that will certainly linger, and for the duration the seal never took his inquiring eyes off Elias’s own. As the current slowed and settled into not much more than a little eddy, the boy’s feet touched bottom and the seal was gone. Elias splashed toward shore, toward his mom, eager to give voice to this extraordinary experience.

Of course, she had seen it all and was no less eager herself. Breathlessly, they blurted out the details simultaneously, and as they did, Drew, who had also seen everything, shouted out his intention to launch his own ride. Elias and his mom looked up at the head of the rapids as Drew signaled his readiness and jumped into the current.

The seal, having scurried easily back upstream during the intervening seconds for a repeat of the thrill it seemed to have enjoyed coming down with Elias, popped up as before, right in front of Drew, and gave him the same companionably breathtaking ride downstream.

This time, though, when it was over and Drew’s feet touched bottom, the seal lingered. It looked at Drew and then at the others onshore. It paddled around him, at times bumping him gently until Drew tentatively reached out a hand and stroked its back as it drifted back and forth. After a few minutes it submerged and disappeared.

Drew splashed ashore to join Elias and his mom. Each blurting out his own frenzied version of events, the two boys suddenly realized that this adventure might not be over, and raced up to the top of the rapids for another dance.

Alas, the seal had apparently had enough excitement for one day, and had moved on out into Winter Harbor—presumably to find its own family and relate its own version of this fun encounter with another species.