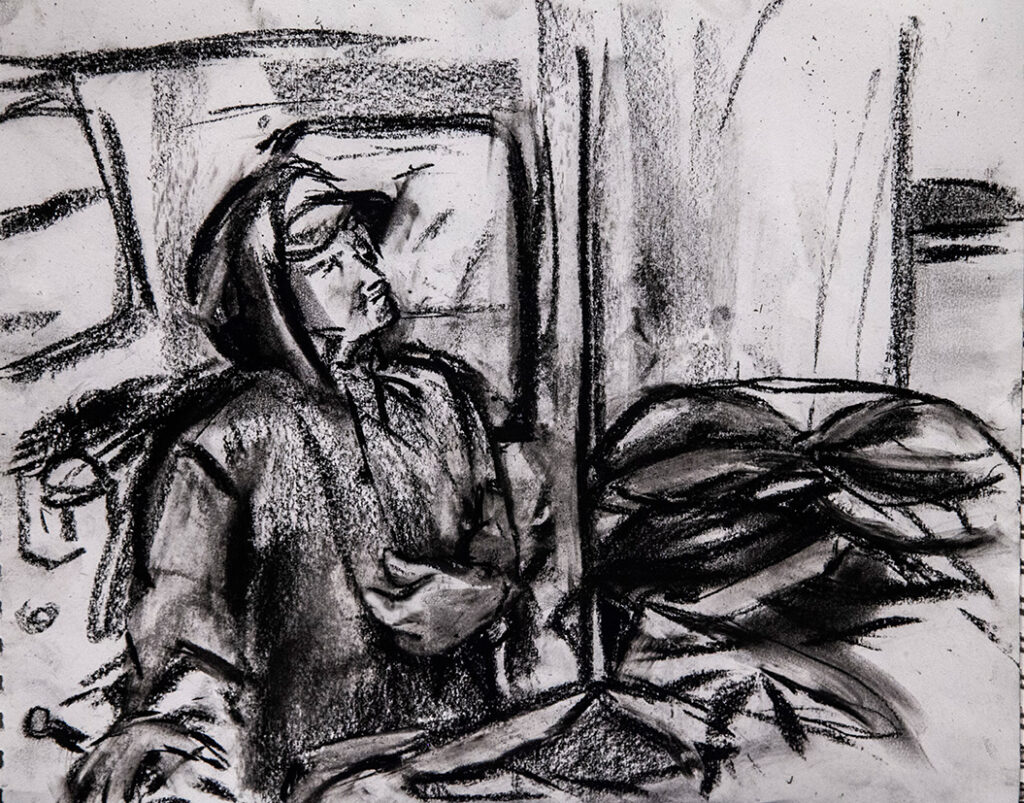

Illustrations by Leslie Bowman

Five degrees above zero and the diesel motor chugged. My fingers were wet and numb and my hands couldn’t work the clasp on the chain-link bag of mussels that hung dripping salt water and mud onto my hood, shoulders, and face. My blue vinyl gloves had already frozen into salt ice that crumbled as I worked. Two of my fingers were wedged inside the two-inch steel ring that was meant to serve as a release for the bag of mussels, but I couldn’t get it to release.

Spencer angled his shoulder into the mussels, tried to brace the bag against the rocking of the boat. The bag was a huge web-work of iron rings. Full of mussels and mud, it must’ve weighed over a ton. The bottom hung level with our chests, and it swung and slammed us against the plywood sorting table. Spencer hollered at me over the engine roar—I had to pull the goddamned clasp before we were pounded flat.

I crouched halfway beneath the bag, soaked, freezing cold. Everything was turning to ice, even the mud, and if any of the rusted cables or rusted fittings or old shitty-looking hydraulics on the drag malfunctioned, I’d be crushed.

Spencer stood off to the side. He wouldn’t go under the bag. He’d been working on a mussel dragger long enough. The guys who went under the bag kept quitting, so that was my job. Stand under the bag and pull the fucking ring.

The mussels were supposed to drop from the bag into a cylindrical steel cage called either a washer or a hopper. The washer was large enough to hold a horse if the horse had no legs and no head, and the entire apparatus was held to the stern of the boat by two hydraulic arms.

Finally the captain charged to the stern. He yelled and motioned for me to snap the ring to the side, not down or back or whatever way I was tugging on it. I yanked it hard and a charge of pain shot through my fingers and up my forearm and landed in my elbow.

The mussels dumped instantly, poured over the stern and into the ocean and onto my feet, banged everywhere with sharp metallic clinks. Spencer shouted and tried to position the bag over the washer. I tried to help. Everything was big and metal and mussels rained down like hailstones. Seaweed and mud and rocks—undersea rocks that weighed more than me—spilled from the bag and splashed into the washer.

I re-latched the bag and Chris, the captain, yelled, “Set?”

I turned and nodded to him. He was in the wheelhouse, enclosed by a shabby plywood affair that looked like it should have fallen over in a gust of wind ten years earlier. A rusty propane heater blasted at him. He worked a series of hydraulic levers with his left hand, fed himself powdered doughnuts with his right, and steered with his thumb or elbow or whatever was free.

He kept singing country songs in a loud, heartfelt manner. Any bad moves on the levers while singing and munching doughnuts—even a twitch as a wave hit—would mean that I, and probably Spencer too, were done. One slip totaling a fraction of an inch and we’d be gone.

Why I trusted Chris so completely, having just met him that morning, and having just watched him and Spencer do an apparently rehearsed air guitar routine as the boat’s engine warmed, was simply because I’d learned a little bit about where the two of them were from.

We’d left that morning from Alley Bay, a small cove off the eastern pitch of Beals Island. Both Spencer and Chris were Beals from Beals Island, and they’d both gone to Jonesport-Beals High School; Spencer was Chris’s uncle, although they were roughly the same age—early 40s. They were from a long line of boat builders and fishermen, and that’s what they did. They built boats and they fished boats and on weekends, they raced boats. Spencer’s father, Mariner Beal—Chris’s grandfather—remains a legend in Maine boatbuilding, and he and Spencer’s older (much older) brother Isaac—Chris’s father—had designed and built one of the iconic Maine lobster race boats: the Christopher.

From Alley Bay, we’d steamed east out of Moosabec Reach, which at its narrowest is a quarter-mile wide swath of water that separates Beals from the mainland. Beals had “settled” the island in 1775, but it wasn’t until 1958 that a bridge was built, a project inspired in part by the uncanny success of the Beals Island basketball team throughout the 1950s—kids wearing sea boots took wooden boats across the Reach in order to get to games that they won, one after another, year after year. They practiced in those sea boots, saved their sneakers for game-time, and became state champions.

We followed a series of ledges then cut northeast to duck into the Thoroughfare, a snaking deepwater channel winding between Roque Island and the two Spruce islands, Great and Little. The Thoroughfare water was calm, green, and the Old Salt was the only boat out, its engine noise echoing off the ledges as we passed.

The land on both sides squeezed like a canal. A lichen called usnea hung yellow-gray from spruce and fir branches and below those branches the smooth striations of the granite ledges flared pink in the cold morning light. I stood on the stern, my hands tucked in the bib of my orange oil pants, and watched the islands glide by, the smooth V of our wake rolling against the shoreline.

Once through the Thoroughfare, other islands blinked by—Double Shot and Anguilla and Halifax to the south, and beyond them the open ocean. To the north, the mile-long stretch of white sand beach on Roque Island. We crossed Englishman Bay and ran up the Little Kennebec River, the land once again closing in on us like framework. When we came to a sharp bend in the river, an old shingle-sided farmhouse off our starboard rail, Chris turned to us, nodded, and said, “Here we go, boys,” and with a flick of his wrist the drag dropped into the water.

Now the bag was out of the water and empty. Spencer and I latched our fingers into the iron rings and swung it back and forth to gain momentum. Then heaved. Chris worked the hydraulics, and as we let go, he released the cable and the empty bag plunged into the sea. Bubbles charged the surface. Mussel shells and flecks of seaweed—dulse, rockweed, kelp, sea lettuce—drifted in our wake. When the drag caught on the soft mud bottom, the boat lurched and the diesel chugged.

The sun cleared the tree line. Light spread over the river corridor and the temperature began to climb but my hands remained a mix of pain and numbness. I drummed them against my biceps, trying to beat the blood into flowing. Cold sweat traced my ribcage. The salt river was clear and green and cakes of ice the size of houses drifted with the current. An old wooden lobster boat hull lay on its side, derelict on the bank. The tide ran hard and pushed the Old Salt cockeyed, like a gull quartering into the wind.

With the washer full and the drag back on bottom, I thought we’d have a moment to collect ourselves, but Spencer pointed at the half-submerged washer and told me to climb over the stern and get into the washer.

“Got to pack them down,” he said. “To get the door closed.”

I thought he was kidding, but his face was serious and impatient, so I climbed over the stern—out of the boat—and stood atop the mussels in 35 degree seawater that nearly filled my rubber boots.

I held tight to the stern. Propwash shot from the propeller, rose in surges around my ankles. On either side of me, deep green water slid by; a half step back and I would be in the ocean. It was like waterskiing behind a dragger in the dead of winter.

In the boat, Spencer pulled seaweed from his beard. Chris, at the helm, sang and played air guitar, using a pinch of doughnut as a pick.

I stamped the mussels down, sinking into hollow spots that nearly pulled my boots from my feet. Above and behind me, the drag cable danced and sparks of water shot from its taut steel strands. Our wake rose like banks of earth, and the boat lurched and pulled against underwater rocks and ledges, mud pockets and shell heaps.

When I finished, I climbed back into the boat and braced my pelvis against the stern, hung over the edge and flipped the door closed. I pulled the latch tight and gave Chris a thumbs-up. The washer lowered into the water and began to spin, a great plume of mud erupting in its path.

I’d met Spencer two years earlier. I was a sternman on a lobster boat, and the captain I worked for had hired Spencer to do some fiberglass repair work on the boat. He and his wife showed up in a rusty Oldsmobile with a license plate that read MamaTrd.

Spencer was stocky, broad-shouldered, bearded. He wore thick glasses, sweatpants and sweatshirt, old slippers, and a baseball hat so covered with bits of mud and seaweed and fiberglass dust that whatever it had once said had long ago been rendered illegible. His wife waited in the car while he looked the boat over; he didn’t say much, only nodded and said, “Yup,” once in awhile.

Months later, I stopped by his boat shop. The shop, called Uncle Bunk’s Boat Shop, was a galvanized Quonset hut he’d salvaged from an old movie rental place called Mrs. Big John’s.

The sign (Mrs. Big John’s Video) still hung inside, each block letter nearly two feet tall. Built in the Downeast style—a hodgepodge of salvaged materials—Spencer’s shop wouldn’t pass code by any stretch of the imagination, and as I stood there, I had to wait while he cut away several structural roof trusses with a chainsaw in order to fit a 40-foot lobster boat inside for winter repair work.

A refrigerator that wasn’t plugged in stood next to an unplumbed toilet. The refrigerator door hung open, a half-empty box of Busch beer inside. Everything—work benches, old hulls, wood scraps, lobster traps, saw horses, boat stands, rope coils (called pot warps)—was covered in a layer of fiberglass dust as if it had just snowed; you could track where people had walked, could tell which tools had been used that day, which had sat for a matter of time, and you could taste the fiberglass on your tongue, feel it in your nose, sense it on your skin like a toxic layer of salt.

I continued to stop by Spencer’s shop. He’d hand me a warm can of Busch from the refrigerator, say, “There’s always room for dessert,” and then show me what project he was working on.

He did a lot of the fiberglass work for the local lobster fleet. I’d drink my beer and ask questions about hulls and boat builders, and soon Spencer would get talking about the days when he was a kid out on Beals Island, hanging around his father’s boat shop, the days when the modern lobster boat was evolving at the hands of men like his father, Mariner Beal, and his uncle, Vinal Beal, and their neighbors, names that are now famous in the lobster industry—Harold Gower, Clinton Beal, Calvin Beal, Ernest Libby.

That winter, when I worked aboard the Old Salt, Spencer would call once in a while and ask if I wanted to go for a car ride with him to look at a lobster boat somewhere on the coast. He was a marine surveyor, and he’d have a boat to survey in Stonington or somewhere on Mount Desert Island, and I’d ride along with him.

I’d hang around as Spencer conducted his survey on one boat or another, and I’d ask about lobster boat design and construction. He’d talk about the sheer lines, the flare in the bow, the shape of the stern and keel. He knew every boat model, boat designer, and boat builder on the coast of Maine—and most times, he knew individual hulls, who’d owned it, worked or raced it, modified or wrecked or sold it.

I followed Spencer into the wheelhouse. It was a Dwight Yoakum tune that Chris was working on—maybe someday I’ll be strong, maybe it won’t be long…the half-eaten bag of doughnuts in front of him, powder on his lips. Spencer opened a package of chocolate and cream Ding Dongs and a can of Coke. He hummed along with Chris’s tune as he chewed, drummed away at the air with his free hand. His beard was still caked with mud and seaweed. His black rain jacket hung in absolute shreds, exposing a gray sweatshirt that was already soaked through.

I wore a newer version of the same black rain jacket but my hood was up because I’d been beneath the drag. My head and face and shoulders and chest were covered in so much mud and seaweed and water that I could feel the simple weight of it all. I wiped at the mud on my face, but it was fruitless. I tried to warm my fingers at the heater but I didn’t have time to take my gloves off because to take my gloves off meant taking my jacket off first because the gloves had to be tucked under my cuffs and sealed tight to keep water from running in. So I stood and waited while they sang and ate.

Minutes later, the washer rose into the air and the thick mussel shells rapped together in a deafening clatter. Empty shells and rocks and whelks and wrinkles and urchins and broken ends of seaweed catapulted from the steel cage.

I followed Spencer out of the relative heat of the of wheelhouse as Chris lowered the mussels for one more seawater rinse. We stood at the sorting table—it was a nearly collapsed plywood table, divided into two sorting sections—as the washer stopped with the door facing us, and Spencer pointed to the lever that would release the door. He nodded to me. I jerked the lever, but I couldn’t move it. It was a bent piece of steel the size of my forearm.

I turned and saw Chris and Spencer exchange a glance. I pulled harder, finally threw my weight into it and the door smashed open with a huge thud and the mussels burst out and dumped over the 4-foot-by-8-foot table. I shut the door, and Chris worked the hydraulics that maneuvered the washer back over the stern.

Spencer and I sorted the mussels; rocks and broken mussels and sticks and trash and other shellfish—lobsters, scallops, whelks, urchins—went over the side; good mussels, their shells bluish-black, sleek and shining, went into bushel onion bags that hung from nails at our waists. There was no time to be picky; it was about speed, hand and eye coordination, dexterity. Any rocks or debris we missed would be removed at the processor before the mussels were shipped.

Of course, I was too slow, too picky, so Chris let the boat hold its own course and gently pushed me out of the way and began working his hands over the mussels at a dizzying pace. It was as if one eye led one hand, the other eye the other hand—both hands picked up rocks and sticks and junk at the same time, so like a juggler, at any moment there were a half dozen pieces of debris flying overboard while handfuls of mussels simultaneously slid into the bag.

When he had the bag full, he pulled it from the nail at the table’s edge, tossed two half-hitches over it like a calf roper, and carried the 60-pound bag to the wheelhouse, where he dropped it on the floor.

“Jesus,” I said to Spencer, who was tying his first bushel bag.

“We been doing it awhile,” Spencer said. “Since we was kids. He’s good.”

Two hours later, Chris put ten pounds of mussels in an onion bag and hung the bag in the boat’s hot tank, which was a 35-gallon barrel of seawater heated by the engine. A while later, he pulled the bag out and dumped the cooked mussels onto the wash rail. Spencer and I finished clearing the table where we’d been sorting, and Chris turned the boat down-tide so that the drag worked like a stern-first anchor. We sat on the wash rail and ate mussels, the flesh deep orange in the sun, and flicked the shells overboard as we ate.

By the end of the day we had 130 bushels—almost 8,000 pounds—of mussels piled aboard the 37-foot boat, and I could feel the weight in her cumbersome pitch and roll as we crossed Englishman Bay. The purple bushel bags filled the wheelhouse, surrounded Chris up to his shoulders, and lined the starboard rail all the way to the bow.

The wind had lifted from the southeast while we were dragging the river, and now Chris piloted the Old Salt slowly, angling offshore toward Halifax Island to take the swell on the quarter instead of the beam. Frigid spray pummeled the windshield and spilled from the wheelhouse roof. I watched Chris carefully, told myself that the fact that he hadn’t stopped singing and playing air guitar was a sign that the over-loaded boat was still relatively safe.

In the lee of Halifax, Chris cut the wheel and turned the boat 90 degrees to follow a course northwest toward Lakeman Island, letting the swell take us on the stern quarter. Waves slapped hard against the hull, sending sprays of water into the air, high into the dragger’s A-frame.

The water calmed as we neared Lakeman, then flattened to a Bahama-like turquoise as we entered the Thoroughfare. We followed the southern shore of Roque Island in silence, save for the ceaseless grinding of the diesel engine. We crossed Chandler’s Bay, and Chris again angled us out to sea, keeping the swell on the quarter, then cut back into the protection of the Reach, our entire path like a series of mile-long Z’s through the water.

As we ran up Moosabec Reach, Chris cut the boat north toward the wharf and like a car fishtailing on ice the boat twisted at an angle to the rushing tide.

We tied to the wharf pylons. I looked overboard at the clear, shallow water. Behind me, Spencer lifted a rock the size of a basketball off the floor of the Old Salt—it had come up in the drag and no one had bothered to throw it back overboard—and heaved it beneath the wharf, onto an existing pile of rocks.

He looked at me with a sheepish grin. “That’s my pile,” he said. “Been throwing rocks there for years.”

I stared at the pile. I shook my head in disbelief. The pile looked like it would have taken an excavator and a dump truck to build, but it was just one man and many years.

The tide was nearly low. The men in orange oil gear on top of the wharf stood 25 feet above us. Chris climbed the long, greasy ladder, and Spencer and I stayed on the boat. We spread a length of heavy line across the deck and stacked ten bags of mussels perpendicular across it, then cinched it tight. From up on the wharf, Chris worked an electric winch that lifted the bags up to the wooden wharf deck, where a forklift and refrigerator truck waited.

Spencer grabbed my elbow and pulled me off to the side. “Trust me,” he said, pointing to the 600 pounds of mussels dripping and spinning in the air above us. “You don’t want to be under if she slips. And she does slip.”

Bag by bag, Spencer and I tied-off all 130 bushels. Chris and the dock crew stacked them on pallets and wrapped them with clear plastic wrap then used a forklift to load the pallets into the truck that would take them the to the processor. Chris was paid $5.50 for each bushel bag—less than ten cents a pound. From that, he paid his father for the use of the boat, paid for fuel and maintenance, and paid Spencer and I, who each got $.90 per bag.

Chris’s father—Spencer’s brother—Isaac, waited for us in his truck. He looked like an old salt himself, like one might envision a two-legged Ahab: the captain’s hat cocked at an angle on his head, the trimmed white beard, the red weathered skin. He nodded to me but spoke only to Chris and Spencer.

I turned and watched a line of swell edge across Alley Bay. The small fleet of lobster boats twisted and rocked on their moorings, their noses pointed toward wind and tide, their hulls as smooth and graceful as the swell that rocked them. I thought of the speed of Chris’s hands as he tossed shells and rocks overboard, and of Spencer’s rock pile beneath the wharf, and of all the stories he’d told me about the island’s boat builders.

I turned my back to the water. Spencer and Chris and Isaac were standing next to the truck, talking about boats and fishing beside the same bay their ancestors had stood beside for centuries.

A cast of gulls swooped overhead. Behind the three men, old boats and piles of lobster traps lined the narrow street. I pictured the underwater fields of mussels, oblivious to the vast swirl of sea around them, simply holding fast to some rock.

Spencer turned onto a side street. He pointed out the house he’d grown up in, the dilapidated shop where he’d watched his father build so many wooden boats. We passed Isaac’s home and stopped at the end of the road. Spencer let the truck idle. A field sloped in front of us, leading down to a rocky beach. There wasn’t any snow on the ground, only patches of ice and frost. After a while, Spencer said, “I used to sled right here when I was a kid.”

I waited for more, but he didn’t say anything more. I looked at the farmhouse that fronted the ocean beside the beach, and at the conspicuous car with the out-of-state license plate, and I thought about how much this place of Spencer’s must have changed in the 40-some-odd years Spencer had been alive.

Then I thought of how much it had not changed.

I glanced at Spencer. He stared at the field as though some memory were flooding his vision. I looked at the field and pictured him sledding, his huge shoulders and sprawling beard, and I found myself smiling, an image now flooding my vision, too: this big, kind, bearded fisherman and boat builder, a generation younger than his brother, sledding down a field on a remote island in Maine, rubber boots and hooded sweatshirt on, headed, as always, for the ocean.

Spencer Beal died from leukemia in 2018.

Jon Keller is the author of the novel Of Sea and Cloud. He writes and digs clams in Downeast Maine. Leslie Bowman is a photographer and painter who lives in Trescott.