He sets off at a lope, elbows carving wide circles, with a gait that hints at decades of making room in crowded fields of runners. His shoulders are rippled with lean muscle, brown. Over the first few yards, he loosens, straightening, getting imperceptibly faster.

Passing the graveyard, he points out a rounded, smooth beach rock propped upright among the ancient headstones. It is the size and shape of a blue-ribbon pumpkin squashed flat and set on end. It bears a Great Cranberry Ultramarathon finisher’s medal.

“That’s Mom’s stone,” he says.

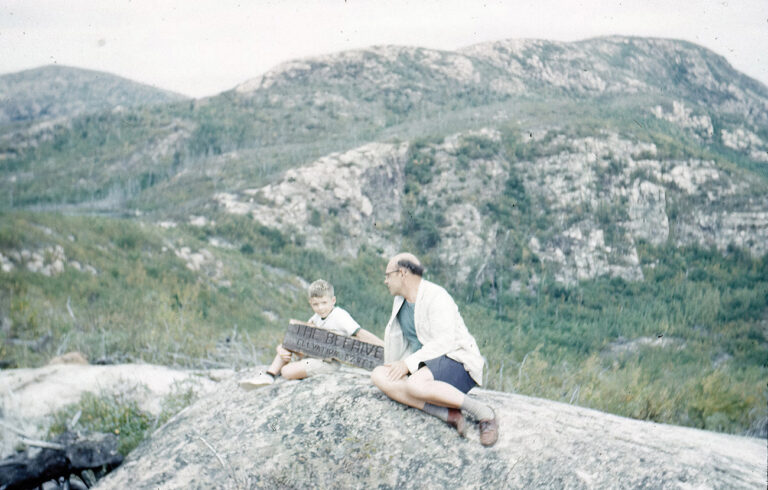

Twelve generations of his family are buried here, in the scarce soil on a long, narrow strip of rock called Great Cranberry Island. He grew up walking along this road, only two miles long: walking to school, walking to the dock to catch the mailboat to Mount Desert Island, walking alone to the pond cradling a hockey stick, pretending he was Bobby Orr.

Now I am running alongside him over a rise and around a small curve in the road, where it turns to dirt. My knees crunch and crackle. We’re both sweating now, not saying much, hearts and lungs awakening, adjusting to this new pace. It has been about two miles. We arrive at a white-painted fence with a gate across the road. Beyond, basking in the sun that has burned haphazard holes in the fog, sits a white clapboard summer house, crisply tended flower beds, a flagpole adorned with the Stars and Stripes.

He reaches out and taps the post next to the gate, then turns, headed back the way we came.

“That’s one.”

Gary Allen is 57 years old. His athletic feats are widely known among distance runners. He’s among only a smattering of humans who have run a sub-three-hour marathon in five different decades. He’s built not one but two nationally recognized races on Maine islands, the Mount Desert Island Marathon and the Great Cranberry Island Ultramarathon. In its final year last summer, the Great Cranberry Ultra—more than 15 laps on the two-mile road—was the official Road Runners Club of America national championship for fifty kilometers. (Asked why he’s ending the Ultra, Allen compares it to both The Beatles quitting at their peak and Woodstock. “You were either there or you weren’t.”)

Last year, he ran more than 700 miles—the first several on snowshoes—from the top of Cadillac Mountain in Acadia National Park to the U.S. Capitol in time for the second inauguration of Barack Obama. It took him only 14 days.

After some back-of-the-envelope math with former Runner’s World editor Amby Burfoot, Allen recently determined that he has run more than 100,000 miles in his life. Roughly 75,000 of those miles were on this two-mile stretch of road.

Great Cranberry Island has 48 year-round residents, down from a high of about 250 in the early 20th century, according to island resident and former selectman Phil Whitney.

In 2000, after years of slow decline, the island’s tiny elementary school finally ran out of students. It’s a familiar story for many Maine island communities: As the school population shrinks, parents and prospective parents look elsewhere for schools, jobs, and homes. The year-round population becomes increasingly older and smaller. The spiral toward a summer-only community begins.

“In order to persuade people to move out here to the island year-round,” says Whitney, “one of the most important things they want to know is that there’s a school for their kids.”

Allen feels a sense of anguish about this. He and his second wife, Lisa Hall, and their 11-year-old daughter, Matilda, live nearby on Mount Desert Island. He spends much of his summer coming out to Great Cranberry to run and see his son Patrick, but the demographic shift has hit him too.

“It’s down to one boat out here now,” Allen says. “This island is really teetering—teetering on the brink. Just in my lifetime, I remember seeing it really thriving.” Running, he says—especially races that bring attention to Maine islands—is his way of reversing this trend.

* * *

Allen usually runs at a pace between seven and nine minutes per mile. So when, as he recently did, he decides to turn an easy afternoon distance run into a 30-miler, that means he’s on the road for more than three and a half hours.

Those 100,000 miles he’s run? If his pace has been roughly consistent for his adult life, he’s been running for over 13,000 hours, or more than one and a half years.

That’s not just time running. It’s time spent in the tunnel vision of a long run, where complicated thought and worry are harder to sustain. The mind wanders. Daydreams appear and recede. Plans emerge and melt away. Sometimes, they stick.

It’s also time spent away from friends, family, and home.

“I’m not a runner,” says Hall. “It’s foreign to me. Some days he’s out early, or he’s out late, but I know it’s just something that he has to do. If he doesn’t run, he’s miserable.”

Allen doesn’t disagree.

“Running has been part of my life for so long now that I can’t really remember not being a runner,” he says. “It keeps me going. It’s like breathing.”

Discussions of running with Allen turn inevitably to the road on Great Cranberry.

“I remember many a time running on this island, looking over there at those hills,” he says, gesturing toward Mount Desert Island, “and actually having my eyes tear up. ‘If I only had all that space, I’d be a really good runner.’ I decided that if runners over there can have all that space, and I only have this, then I have to work twice as hard.”

In 1980, Allen stood on the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, about to begin his first New York City marathon. At the starting line, thousands of runners danced on the balls of their feet, itching for the sound of the gun.

I’ve gotta do this in Maine, Allen remembers thinking. I don’t know how one does this, but I gotta do this in Maine.

For 20 years, he ran, raced, and ran some more. His mileage added up. His legend grew in the small but fanatical world of distance runners.

Then, in 2001, Allen started the Mount Desert Island Marathon.

“I worked at Cadillac Mountain Sports,” says MDI Marathon coordinator Mary Ropp, “and he used to come in and ask to use our printer, ask to make some copies of his poster. I thought, ‘That guy really needs some help.’ That was nine years ago, and here I am.”

Bar Harbor—MDI Marathon starting line—8 a.m., October 20, 2013

The runners are gone. The race has begun. In the middle of Main Street, Allen, his son Patrick, Ropp, and several volunteers are rapidly folding up the metal barricades and signage and loading them into a pickup. The street is wet from an overnight rain. The thick overcast is pierced occasionally by a cinematic beam of sunlight.

Allen hops into the truck, with Ropp riding shotgun.

“We need to get to Southwest ,” he says, nervously. “We need to make some magic happen.”

“You need to not freak out right now!” says Ropp. She is bubbly and positive, talking to him and about him with a bemused expression, like the mother in a sitcom.

“We need to get space blankets, medals, fluids, all those wooden tables. We have well over a thousand finishers. That’s a lot of bodies,” he says.

“It’s really good,” says Ropp, reassuringly.

“Yeah,” Allen says. He is silent for a moment. His face bristles with silver shards of beard. He looks completely exhausted.

Then he turns on the stereo. “Smoke on the Water” blasts in the truck, and he pumps his fist. We are speeding on Route 198. Outside, the trees are brown, green, and red. The wind has died down, and Somes Sound is as smooth as a frozen lake. The air is about 60 degrees. A perfect runners’ day.

Southwest harbor—finish line—8:35 a.m.

Volunteers mill about the damp parking lot in front of Pemetic Elementary School in Southwest Harbor. The sweet scent of damp leaves hangs in the air, and a relentlessly peppy playlist pumps through speakers.

Allen isn’t apt to delegate. Confronted by a pair of eager volunteers, he instructs them to carry boxes of medals over to the finish line. But in explaining where they should go, he begins demonstrating and winds up lugging half of the pile himself. Same thing with the water jugs and the awards for the top three finishers in each age group and category. His shoelace is undone, a volunteer points out. Allen thanks him as he walks by, never breaking stride.

With the help of another volunteer, Allen pulls apart a giant stack of trash cans and begins lining them with bags.

“Sometimes it’s just easier to do it yourself,” he says, thrashing a can liner in the air to unfold it. “Islanders just friggin’ do it. It’s the island way.”

“He has a hard time asking for help,” says Ropp, watching as Allen drags the winners’ podium into the middle of the road. “We’re very particular about things, but at some point you just have to let it go.” Allen is arranging the barricades behind the finish. “I just try to keep him calm,” she says.

Southwest Harbor—finish line—10:28 a.m.

After 2 hours and 31 minutes on the course, local running legend Louie Luchini blazes down the street, following the blue lights of a state trooper’s car. He leans over to high-five Allen on his way to the line.

“I’m exhaling,” Allen says. “It’s like I’ve been breathing in all week, and now I’m finally exhaling.”

Southwest Harbor—finish line—10:56 a.m.

Allen, Ropp, and Ross Lane, a volunteer ham radio operator who’s monitoring reports from the state trooper’s patrol car, are conferring about the women’s race: Will it be Lindsay Willard? She’s a favorite, the women’s course record holder, and a threat to break the record again. She seems to have it in hand. The radio crackles and Ross relays, “They’re at mile 24.5 . . . It’s F2.”

“That’s Lindsay,” Ropp says. “She’s got it.”

But Willard has run the Chicago Marathon only a week before, and somewhere on the hot shoulder of Route 198, where the sun has finally broken through and there’s one last long hill to climb and descend, she falls behind.

“It’s F8,” Lane reports.

“Who’s that?” Allen asks.

“Leah Frost. Vermont.”

“If she breaks three hours she gets $500,” Gary says, brightening. The clock ticks past 2:57, 2:58.

Blue lights flash over the rise of Main Street, and Frost appears, a compact woman, brown hair in a pair of braids.

Suddenly, Allen sprints up the road toward her, thrusting his arms over his head and hollering, jumping in the air every few steps, in the manner of someone trying to warn oncoming traffic that the bridge is out. He’s encouraging her, begging her, willing her to the line.

She sprints past us in a blur with a big smile on her face, and the crowd roars. Allen’s daughter Matilda and a friend hold up a big, black ribbon. She dashes through it.

2:59.

On the podium directly behind the finish line, as runners shuttle past in various states of anguish, Frost, wrapped in her crinkly plastic blanket, beams as Allen places a wreath on her head.

“This is Leah Frost from Vermont,” he yells to the crowd. “She just set the new course record, and she’s the first woman to run under three hours!” She waves her bouquet and smiles.

Willard is escorted past her to the medical tent, a vacant stare on her face like she’s receiving bad news by phone. Volunteers support most of her weight, and her feet seem to glide across the ground.

The finishers keep coming for hours. Music continues, and a volunteer in the timing truck calls out the name of every finisher as they reach the line.

Beyond the finish, in the school parking lot, runners wander around and talk. Flushed, wet faces beam. Runners take to patches of dry pavement and grass with satisfied grimaces. Aside from the crinkle of plastic blankets, the predominant sound is laughter.

Allen stands near the line, watching them come.

“We won’t be out of here until seven o’clock tonight, and then we’ll spend all night picking everything up.” He sounds proud.

Ropp, standing next to him, admires the result of their work.

“What I’m seeing now,” says Allen, “is that this is possible,” as though he’d ever conceded that it weren’t.

“It always comes together in the end, right?” Ropp laughs, heading over to assist a volunteer trying to move a folding table.

Allen just smiles and shakes his head.

* * *

It’s January and I’m on the phone with Polly Bunker. She’s lived on Great Cranberry for 86 years, and Allen is her nephew. He recently announced his plan to run from Cadillac Mountain to the Meadowlands for the Super Bowl, becoming both the first to do so and possibly the first to want to. He is raising money for the Wounded Warrior Project in the process. The fund-raising appeals he contrives for these runs seem at first like mere justification, but it becomes clear that his enthusiasm is genuine: If Gary’s going to do this crazy thing—and of course he is—then he wants someone deserving to benefit from it.

As a boy, Bunker remembers Allen being energetic and impulsive. One sweltering day long ago, she saw him walk by her gift shop door, shirtless and carrying a chain saw.

“Where are you going, Gary?” she asked.

“I’m going up to that piece of land to build myself a house.”

Before he did that, Bunker asked, could he help her construct a window to cool off the inside of her shop? She assumed this would be a couple of days’ work.

Instead, Allen walked in, fired up his chain saw, and cut a rectangular hole in the wall from one stud to another. He added a secondhand hinge to the extracted piece of wall, reattached it, and headed up the road.

“He built the house, too,” she says with a chuckle. “It’s still there.”

I ask Bunker whether the demographic slide that Great Cranberry has in common with so many other small towns in Maine is at the root of Allen’s passion for running, for publicity, for pursuing athletic feats that are painful, difficult, and dangerous.

Bunker isn’t so sure. And at this point, neither am I. It doesn’t add up. His races and spectacular achievements really do cast attention on the town he loves so much. One could argue that the MDI Marathon has extended the tourist season on MDI, a critical benefit to a place so dependent on visitors’ dollars.

But it doesn’t seem possible that Allen—the same Allen who careens over rural roads with traffic cones and goes sleepless the night before race day, the Allen who lay in the dark in Philadelphia, battered and sore, and got up the next day and ran on toward Washington—it doesn’t seem possible that this man decides to do these things because of economic metrics or public relations strategy. Something deeper is driving him. Something insatiable.

“Charlene was that way,” Bunker says of her late sister, Allen’s mother. “She was energetic and full of life. She was always mingling with people. She drew energy from it.”

I think of Allen, pumping his arms at stragglers on the marathon course and bear-hugging volunteers.

She sighs. “It’s been really hard losing Charlene. Hard on all of us.” She pauses. “He really is different, though. You’d think he’d do it, say ‘I’ve done that,’ and forget about it. But there’s still something in the back of his mind. There’s still something more he needs to do.”

* * *

After the run to New Jersey is over and Allen is recovering, he tells me about the fifth day of that trek. In York, Maine, south of Portland, he began to shake violently while he was running. Soon, his vision began to deteriorate. Rattled, he asked his support team to take him to the hospital. He was severely dehydrated. He’d simply exhaled more moisture into the frigid, dry air than he was able to drink. After three units of saline through an IV drip, Allen put his shoes back on. He ran to Massachusetts before calling it a day.

Why do this? I ask him.

“You feel a little empty if you don’t do it,” he says. “I was taxing my body a lot. And I kinda liked it. I had never been that fatigued before, and I wondered, ‘Is there anything beyond this level of fatigue? Or is this it?’”

In the end, there is no answer; only a question.

Allen’s obsession, his drive to run great distances—and to be recognized for it—is both strange and familiar. The training required to be a good runner—especially a distance runner—demands hours, days, and weeks of obsessive focus. Thousands of people might run the same marathon, but each has trained alone. Each has fantasized about the race in the midst of a long run, sweating and chafing under the weight of a dream shared with no one. Each runner’s training schedule caters to his own needs over anyone else’s. And every runner who’s a parent—myself included—has had to ask someone else to keep watch over his children so he can go off for an hour or two, alone, to run and dream.

Running is a selfish pursuit. It is an old, ingrained desire; it’s older than conscious thought. It’s older than planning, older than conscience. Allen is its embodiment. Running is like breathing.

* * *

At town meeting in March—Great Cranberry is one of five islands in the town of Cranberry Isles—residents voted to keep Great Cranberry’s Longfellow School open, despite a lack of students, for the fourteenth straight year. The school provides a home for the library, and is one of the only public spaces on the island. But those who voted to spend town money to rehab the building—as Allen did—are hoping for more. They hope the island will once again have enough children to hold classes. Until then, they aim to keep the building ready.

“Cranberry is struggling,” Allen says. “The place I love that defines who I am is struggling.”

But when we headed back to Great Cranberry on the mailboat after town meeting, you could sense that people had rolled up their sleeves and said ‘We’re not gone yet.’ ”

On Great Cranberry that week, the smooth round stone was under snow and ice. The finishers’ medal from the Great Cranberry Ultra would be obscured, if still there at all. The race itself is over for good.

But something will take its place. Allen’s going to come up with something. Of that, everyone who knows him is sure. Runners, first Allen, then more—maybe a dozen, maybe hundreds—will tramp back and forth along this road, the spine of the island, in front of this graveyard, with the ocean and the mountains of Acadia in the distance.

The road leads from the wharf to the fence post and back again. Repeat.