“The family became so destitute that they were obliged to seek alms from the town. An official from Stonington took the child when she was six years old and started with her for the Poor Farm on Deer Isle.”

— Dr. Benjamin Noyes, Island Family Histories: 1890–1945

Fortunately, this story has a happy ending. Lucetta Kinney heard the little girl crying while passing her home. Not having any children of her own, and pitying the little girl’s condition, she took the child into her home where she and her husband, Ezekiel, brought her up, changing her name to May Kinney.

The concept of the poor farm (or town farm) in Maine originated in the 19th century. During these years, Maine towns began to support people who were unable to care for themselves or their family members. At the time they were described as “indigents” or “inmates.” A poor farm might have included the homeless, unemployed, elderly, orphans, physically disabled, and mentally challenged, as well as single mothers with children.

Prior to the establishment of a poor farm, Deer Isle handled its indigents in a variety of ways. Beginning in 1817 the town voted the sum of $500, “to allow town overseers to expose the sale at public auction of the poor of the town to the lowest bidder.” Then, in 1842, Edward Small was paid $485 yearly “to care for paupers.” A few years later the town voted to “instruct the overseers of the poor to make sufficient accommodations at the poorhouse for paupers, and to bind out all the paupers that they have a chance to,” suggesting that there was still a need for permanent accommodation.

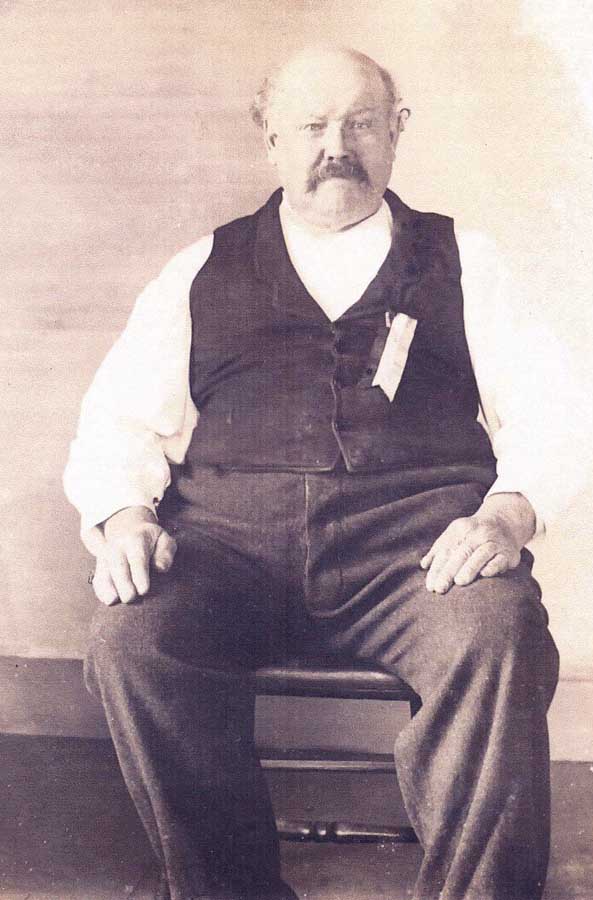

Joseph Weed, a longtime resident of Deer Isle, was born in 1794. He and his wife Judith were married for 60 years, and he was described as “very industrious, prudent and a good citizen.” He even worked as the town’s tax collector for a number of years. As an old man, however, Weed fell on hard times. Ironically, the former town employee’s lands were taken over by the town shortly before his death in 1855. George Hosmer’s An Historical Sketch of the Town of Deer Isle, Maine, notes that “The town obtained possession of Joseph Weed’s farm and used the premises as a Poor Farm.”

Connie Wiberg, archivist at the Deer Isle-Stonington Historical Society, says that in 1860, David Torrey, a cooper who lived on North Deer Isle Road, was put in charge of the former Weed farm, “ it for the town as a Poor Farm.” Torrey, age 53, and his wife Eliza, age 47, took care of 12 people who were termed “insane, pauper and idiotic,” and ranged in age from 18 to 90.

The town sold the farm in 1881 for $325 to George Blastow, who ran it as a private operation for a number of years. When the Blastow farm closed in 1907, Deer Islanders returned to their previous approach of boarding out indigents to individual families. In the early 20th century there were anywhere from 6 to 15 people who were maintained in private homes at public expense.

The old Weed farm was not the only poor farm on Deer Isle, though it was the most significant. Records indicate that in 1882, a man named George Gray operated a poor farm on Center District Road, in a house now owned by Hugh Frey. No other information is available, though it was apparently “the last Town Farm on the island.”

Silas Banks is an interesting example of the kind of person the town cared for in these poor farms. As described in Hosmer’s history of Deer Isle, Banks “fell into distress after his father gained a settlement here, and the town was holden for his support and was obliged to provide for and remove him until his death in 1872.” The description adds poignantly, “He was a very witty person and in some things possessed a good deal of shrewdness.”

By the time she was an old woman, Bryant had become a town charge. A certain tale, elaborated on over the years, describes how she had hidden her life savings under a tree in the woods. One day a town selectman took her to the woods in an attempt to help her locate the spot. As the years passed, hunters trying to shoot rabbits in the area “found their shots ineffectual as the rabbits scurried to cover unhurt.” The theory was that Betty had cast a spell over the area.

One Sunday morning some hunters stopped at the poorhouse where Bryant lived. She proceeded to “admonish them for hunting on the Sabbath day. . . . Her old form shook with passion.” The story goes that an old soldier then loaded a silver button from his military coat into his gun and shot a rabbit. When the hunters returned, Bryant was found dead, killed by the silver button.

Dr. Benjamin Noyes, who compiled a history of Deer Isle in his book, Island Family Histories: 1890–1945, wrote, “Many ridiculous events I have heard attributed to power, and the stories, probably losing nothing in the telling, have passed down to the time within my memory. Intelligent people repeated these fanciful tales and no doubt many believed them.”

Islesboro’s resident historian Paul Pendleton is in his 80s and has lived on the island his entire life, except for a three-year stint in the navy during World War II. Pendleton remembers when the Islesboro Poor Farm was operating and Melvin Grover was the caretaker.

According to Pendleton, an Islesboro poor farm opened in the late 19th century, when the island’s population was double what it is today. Starting in 1850, the town spent $300 annually to support “six native paupers.” In 1860 the number had risen to 27 paupers, who cost the town $575. By 1880, however, Islesboro’s town register notes the number of “indigents” had dwindled down to 5, “expense unknown.”

As noted, Melvin Grover was not the first caretaker of the town’s poor. In 1926 George Sherman was paid a salary of $1,300 to manage the poor farm. Four years later the Great Depression had already begun when Don King took over as caretaker. It was King’s misfortune that the caretaker’s salary had been reduced to $1,200 by the time he assumed responsibility in 1930. From there it only continued to decline.

Prior to assuming the caretaker’s job, sometime in the mid-1930s, Melvin Grover had worked as a butcher and an island handyman, and, until cars came to the island in the 1930s, he was also the town’s mailman, delivering the post by horse and buggy.

Grover needed a stable job and money to support his growing family when he took over the poor farm. “He had lots of children,” Pendleton remembers. “He was only married once, but he and his wife had two sets of kids, probably seven or eight in all. When one batch grew up, they had a few more.” As of 1943, however, Grover was still only paid $750 to manage the poor farm. Clearly the island was still feeling the effects of the Depression.

Usually there were between six and eight residents on the farm that Melvin and his wife managed. Most were men and women in their 40s and 50s, and all were described as “mentally unstable.” Paul cited the case of an elderly woman who died, leaving three sons. The young men were unable to manage for themselves, so they were sent to the poor farm.

Pendleton recalls that Grover “probably ran the place for 10 years, until he started to decline mentally in the early 1940s.” Grover’s mental problems became apparent in 1943, when he ran away from his job. The whole island turned out to look for him, including Pendleton, who found Grover hidden in a barn about a mile from the poor farm. Pendleton knew he was there when he heard coughing up in the hayloft.

Melvin Grover died the following year, when Paul thinks he was in his 60s. Knowing he was mentally unstable—indeed, possibly suicidal—the town had lined up a less-stressful job for him, working in a Camden shipyard. However, when a man arrived to help him move to Camden, Melvin ran away again, and this time, committed suicide.

Following Grover’s death in 1944, the remaining town poor went to live in Idella Wentworth’s house on Oregon Road. Idella lived alone and ran the place herself. In 1946 the town budgeted $3,000 to pay the costs of managing, boarding, and burying the people who lived with Idella. “At that point,” Pendleton says, “no one was in such bad shape that they had to be restrained.” There were, however, a number of references for “doctors’ care” and “hospital expenses for Roy Whitten” in the town records.

The 1946 Annual Report of the Town of Islesboro additionally listed $315 spent to send Lena Dodge to the Murray Nursing Home, and $615 paid to the New England Home for Little Wanderers, for Peter and Darrell Dodge. By 1959, however, everyone living with Idella Wentworth had either died or been sent away.

Growing Up on the Poor Farm

For most of the 19th century, Vinalhaven residents unable to care for themselves were boarded with other families at the town’s expense. In 1894, when it became difficult to find enough places to board these residents, the town bought a building that had been part of a large farm on Vinalhaven’s eastern shore, and the island’s poor farm came into existence.

Records in the Vinalhaven Historical Society indicate that the land and buildings originally cost the town $900, “including three bedsteads, four carpets and curtains.” The poor farm operated from 1894 to 1943, and had seven different managers—or “proprietors,” as they were called—including Lorenzo Bunker.

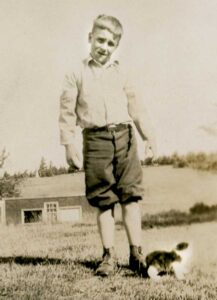

Lorenzo Bunker’s son Woodrow was born in 1918, and has vivid memories of growing up on the island’s poor farm (although he always felt this was a derogatory term). His father Lorenzo got the job as superintendent in 1924, and was paid $30 a month. Woodrow Bunker remembers that when they arrived, there were nine elderly people living there. Each had his or her own room with a bed, bureau, and a couple of chairs. They also had a lamp and a box of matches. “Can you imagine nine old people carrying lamps around?” Woodrow recalled in an interview before his death in 2006.

When the Bunker family arrived, the building had no electricity or running water. Drinking water came from a spring located 600 feet away from the house. Bunker remembers lugging two buckets of water at a time and dumping them into the old washtub, and filling the boiler for his mother. Mrs. Bunker had her hands full doing the cooking and cleaning, along with caring for her own five children and two elderly women in wheelchairs. (There is no mention of Mrs. Bunker receiving a salary.) Some of the residents came and went, but most stayed until they died.

Bunker’s father Lorenzo tended a large garden, milked the cows, cared for the animals, did the food shopping, cut the wood, and stoked the stoves. He also slaughtered the pigs when needed. Bunker remembers, “Some of the elderly might have helped with chores, but not often.”

Bunker lived with his family on the farm from 1924 to 1936, and recalls “a beautiful boyhood.” He fished, played with neighborhood boys, and rode to school in a horse-drawn wagon. High school students weren’t allowed to ride this “bus,” so at that point he had to walk. “I’d walk home at night, have supper, walk back down to play basketball, and then walk home again. I was getting 16 to 20 miles each day just walking.”

Bunker has vivid memories of some of the residents:

“Ninety-year-old Jane Springer would slip out her window at night and head for town like she was sixteen. My father used to go chase her and bring her back. . . . Frank Pease was a big man who probably weighed 300 pounds. He drank a quart of tea with every meal and read the Bible a lot. . . . Fanny Dyer cured the warts on my hands. I was always grateful to her for that, but I don’t know how she did it.”

Then there was the peripatetic William “Hunk” Beverage, who must have set a record for leaving and returning. Bunker describes him as “coming in and out as he found work.” Beverage was admitted in March 1926 and left the next month. He returned in November 1932 and left in February 1933. He was admitted in November 1933 and left in January 1934, only to leave again in March of the same year and return in November 1934. Beverage came and went a total of 12 times before his death in 1941.

Priscilla Chilles Rosen remembers going to the poor farm on weekends to visit her cousin Mary when she was in high school. (Priscilla’s uncle, John Chilles, managed the farm from 1940 to 1943.) Priscilla told me, “Most of the people were infirm and didn’t have anyone to care for them, but they did have a good vegetable garden and ate well.”

Longtime North Haven resident Lewis Haskell remembers two brothers, Wilbur and Rome Norton, who lived on North Haven. When their father died Wilbur inherited the family farm. Since Rome was unable to care for himself, the town of North Haven paid for him to live at the Vinalhaven poor farm.

There is no record of a North Haven poor farm, although there are listings for “Support of the Poor” in the town’s annual reports. These go back to 1837, when Nelson Carver was listed under “Poor Children Bound Out.” Nan Lee at the North Haven Historical Society says that the town paid for a number of individuals to “board out,” which extended to supplying clothing and general supplies to the poor. North Haven also paid the costs of an “Insane Hospital” and a “Home for the Feeble-Minded” for two people. Interestingly, even today, one of the North Haven selectmen’s titles is “Overseer of the Poor.”

Poor farms were not a complete drain on the island economies. By producing milk, vegetables, wheat, eggs, pork, beef, and veal, they were able to defray some of the operating expenses to their respective towns. In 1897 produce on the Vinalhaven poor farm amounted to a profit of $282.69, and on Islesboro, a 1931 entry reads “Received from Town Farm, labor and produce, $1,032.73.”

The End of the Poor Farm Era

In the first part of the 20th century, the populations on Deer Isle and Vinalhaven dropped significantly due to the decline of the granite industry. This was followed by the Great Depression and World War II, which further reduced island populations. Men and women left to look for work on the mainland, and, in the case of World War II, many joined the armed forces.

Vinalhaven’s population declined from 2,334 people in 1910 to 1,427 in 1950, a drop of almost 39 percent. Islesboro, which never had as large a population, went from 697 people in 1930 to 529 year-round residents in 1950, a decrease of 24 percent. Similarly, Deer Isle lost 1,000 people from 1910 to 1950.

Island populations continued to decline until the 1970s. With the extension of state and federal social services, including the Social Security Act in 1935, the need for poor farms disappeared, although Islesboro’s Idella Wentworth carried on until 1959.

In 1946 George and Ann Harwood bought Islesboro’s poor farm for $1,800. Today their niece and her family still spend their summers in the renovated farmhouse. The Harwood house sits on a hill on 59 acres at the north end of the island. On a nice day one has a beautiful view across the waters of East Penobscot Bay to Castine.

The original Joseph Weed farm on Deer Isle went through several more owners until it was sold to John and Marcia Winn in 1941. Winn family members and their relatives have owned the property to the present day. In 1928 the owner was Otis Howe, who named it “The Larches,” as it is still known today.

Except for the occasional squatter, the Vinalhaven poor farm sat empty until 1956. That year Mauricio and Emilia Lasansky bought it from the town for $1,500 and began fixing the place up. For years Lasansky family members used or rented out the building for printmaking and other artistic endeavors, including sculpting, dancing, and poetry writing.

Horace and Alison Hildreth bought the Vinalhaven poor farm in the 1990s and have continued to rehabilitate the old building. When I told Alison I’d heard rumors the place was haunted, she related the following tale.

The Hildreths had been renting the farm to a group of graphic designers on retreat for a number of years. One night when everyone had gone to bed, a bloodcurdling scream was heard. A young man bolted from his room on the second floor. Apparently he had woken up and seen what appeared to be a young woman standing at the end of his bed. He was so startled he didn’t wait for her to disappear, and fled from his room. He insisted on sleeping elsewhere for the rest of the retreat.

When Alison relayed the story to her family, her daughter-in-law said her aunt had slept in the same room and had had the same experience.

Alison herself has stayed in the room many times and has never been bothered. “Ghosts don’t make themselves visible to everyone,” she said. “It isn’t all nonsense. If they were ghosts, they were friendly ghosts.”

Harry Gratwick is a lifelong summer resident of Vinalhaven and the author of five books.