As the Gulf Coast waited for Hurricane Michael to make landfall in the fall of 2018, residents of the Tanyard a low-lying, low-income community in Pensacola, Florida, posted updates on their online neighborhood bulletin board. Gloria Horning, co-president of the Tanyard Association, wrote, “Folks, please check your storm water drains. Clean them to allow water to drain during the storm.”

A day later she uploaded photos of a flooded South Devilliers Street with the caption, “It hasn’t even rained yet.” High tide was working its way into the neighborhood through the very underground infrastructure that was supposed to usher water out. Other members sent links to locations where residents could get free sandbags, lists of local evacuation shelters, and minute-by-minute updates on the city’s emergency preparedness plan.

As flooding has become more common and internet access widespread, groups like Horning’s have started popping up across the nation. There is “Thomas Flood & Mud Watch Updates for Ventura & Santa Barbara Counties” ; and “Fix Flooding First!” in Charleston; “Houston Flood 2015 & Beyond: Support and Resource Group”; and “Acadiana Flooding Message Board” in Lafayette, Louisiana. Some have 20 members, others 12,000. Most began with the goal of helping residents weather a particular storm and then access the resources made available for recovery.

During big hurricanes, like Michael, folks post information about who needs to be rescued and where. Then, in the aftermath, members ask and respond to questions: How do you file a National Flood Insurance claim? Which companies are best at lifting homes? And, can you pursue this option if yours is built on a slab?

Anyone who has lived through a flood will tell you this much: it’s deeply unsettling. You watch the water creep under the door and know that soon the floor will buckle. That the sheetrock will need to go and the family photos will warp.

That the home you built, made your life inside of, is in the process of coming undone.

But when one flood becomes two, then four, then eight, can-do gumption turns into curiosity about causes, and a desire for justice. Along with human accelerated climate change, development practices have also amplified the disruptive power of unprecedented weather events.

I have been reporting on flooding and the early effects of sea level rise since 2012. During that time, floods and extreme rainfall events—events that once felt like isolated and isolating experiences—have become more common. With this increase in frequency, many of those living on the front lines of climate change are waking up to the fact that they are not alone and that the floods they suffer are, in many ways, man-made.

From Wetlands to Wet Lands

Wetlands act as giant sponges, absorbing both storm surges and rainfall during extreme weather events. But when they are paved over, that water still has to go somewhere. Over the past 200 years many states along the Eastern Seaboard and Gulf Coast have lost over 50 percent of their wetlands to development. And in some metropolitan areas the statistics are mind-boggling. From 1992 to 2010, Harris County, Texas (of which Houston is a part) lost 29 percent of its freshwater wetlands to development.

“We don’t often talk about it, but the way we have developed in low-lying areas amplifies the destructive power of these storms,” says Alan Benimoff, a professor of Geology at the College of Staten Island in New York City, one of the areas hardest hit by Hurricane Sandy back in 2012.

As more and more citizens become aware of the ways in which the development of coastal and freshwater wetlands can increase flooding in adjacent neighborhoods, the mission of these citizen flood groups is evolving. Once the floodwaters recede and life takes on a feeling of normalcy, many have begun to fight future development projects sited atop wetlands.

Residents Against Flooding in Houston began after a thunderstorm inundated the Memorial neighborhood. When events like this repeated themselves, again and again, culminating in the catastrophic flooding that accompanied Hurricane Harvey, urgency around the fight to keep wetlands free from development reached new highs. The group recently filed a federal lawsuit against its Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone, which argues that the board of this public entity facilitated wetland development without the accompanying and legally-required storm water detention, causing neighborhoods that never flooded before to find themselves regularly underwater.

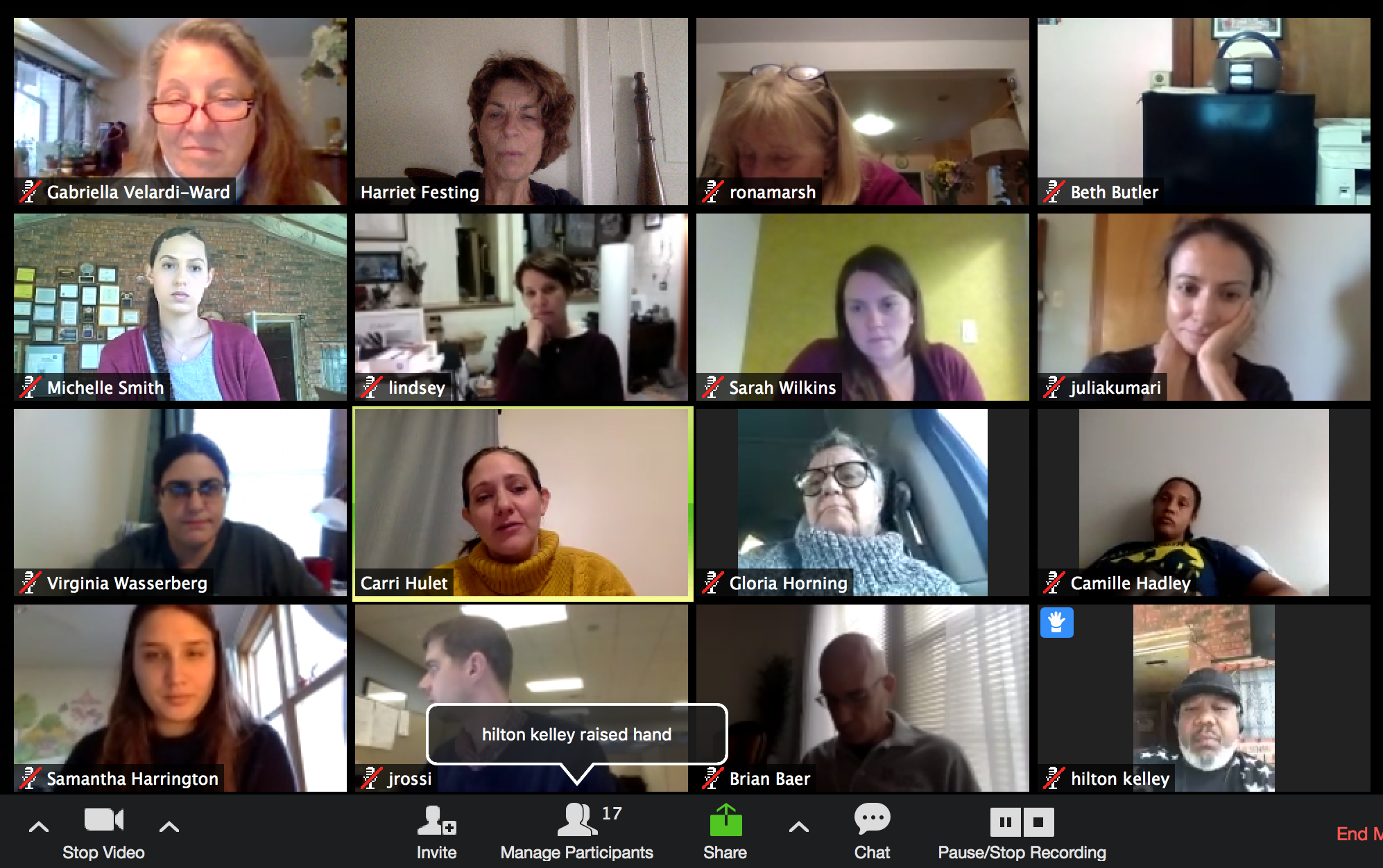

In the fall of 2018, while reporting on the Hurricane Florence recovery, I joined a Zoom meeting set up by Harriet Festing of Flood Forum USA. Founded in April of 2017, on the eve of the single most costly hurricane season in U.S. history, Flood Forum USA is the first nationwide coalition designed to help flood survivors get organized, heard, and supported.

I sipped my green tea as my screen populated with people from around the country. Gloria Horning beamed in from Pensacola and Beth Butler joined from New Orleans. Gabriella Velardi-Ward, the Coordinator for the Coalition for Wetlands and Forests in Staten Island was in attendance, as was Cynthia Neely from Residents Against Flooding. Twenty-seven leaders from dozens of different citizen groups aimed at preventing or reducing future flooding joined in. And while, as of the time of writing, Flood Forum boasts no partner organizations in Maine (though hopefully this story can help change that), the nearby Seabrook-Hamptons Estuary Alliance in New Hampshire and the Massachusetts Coastal Coalition are both members.

Every month, Festing organizes a call to connect local leaders to the information they need. In this case, the call covered how and when to mount a lawsuit against unlawful wetland development. The speaker for the afternoon was attorney Eric R. Nowak of Harrell & Nowak in New Orleans, who explained what was required in order to file such a case and the opportunities for success. The tone was one of conviviality and care, and throughout the hour I watched Festing take notes on what kinds of resources were needed by whom.

“I don’t want each of these local leaders to have to reinvent the wheel every time they are underwater,” she would later tell me. It seemed like a reasonable goal, one made perversely more possible by the existential and social threat flooding increasingly poses as cities around the world continue to pave over their remaining natural defenses while storms get stronger, and the very rate at which sea levels are rising accelerates.

Flood Forum—which has, in the year since its founding, already attracted more than 25,000 members—plays matchmaker, connecting local activists to the support they need in order to address the issue in an equitable manner. It introduces frontline communities to scientists, designers, and lawyers who are willing to donate their time and expertise to help residents understand their flood risk, communicate those risks to local representatives, propose long-term solutions, fight future wetland development, and hold developers who have unlawfully built in wetlands financially accountable for their actions.

All around the world, increased flooding is unsettling our very idea of who we are, where we come from, and the places we call home. And yet, in a strange twist of fate, these events are also bringing communities together even as they simultaneously threaten to break them apart.

We talk about resilience as if it were something we could add to the built environment by turning seawalls into dunes, and replacing concrete with rain gardens. This is one half of the equation and it is the costly half at that. It’s the half that many places aren’t likely to get because they have long been at the bottom of various municipal lists.

To all, but especially to those whose neighborhoods have always been under threat, let us also define climate change resilience this way: it is a human act, one of coalition building and fostering solidarity, one that promises to rewrite power relationships, and even mend our relationship with the land, as we continue to recognize that this vulnerability is widely shared.

Elizabeth Rush is the author of Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore (nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in the general non-fiction category) and Still Lifes from a Vanishing City: Essays and Photographs from Yangon, Myanmar. Her work explores how humans adapt to changes enacted upon them by forces seemingly beyond their control, from ecological transformation to political revolution.