In considering the life of Ed Monat—the Bar Harbor–based marine educator often referred to as Diver Ed—I began to think of Sir Arthur C. Clarke’s assertion, “How inappropriate to call this planet Earth, when clearly it is Ocean.” In the course of Monat’s life as a lobsterman, underwater nature trail constructor, scallop diver, commercial diver, scuba diver, technical diver, scuba instructor, marine ecologist for the Smithsonian, Bar Harbor harbormaster, and deeply committed educator, he has spent the equivalent of eight years underwater. How inappropriate, one might be tempted to say, to call this man human—human as in “of or belonging to man,” human as in humus, Latin for earth—when clearly he is amphibious, if not in the technical sense, then in the etymological sense of amphi, meaning “double,” and bios, meaning “life.” Monat tells me the only thing he doesn’t like about diving is coming back up. “I just want to keep looking around,” he says. “I just want to keep exploring. That’s just what I do.”

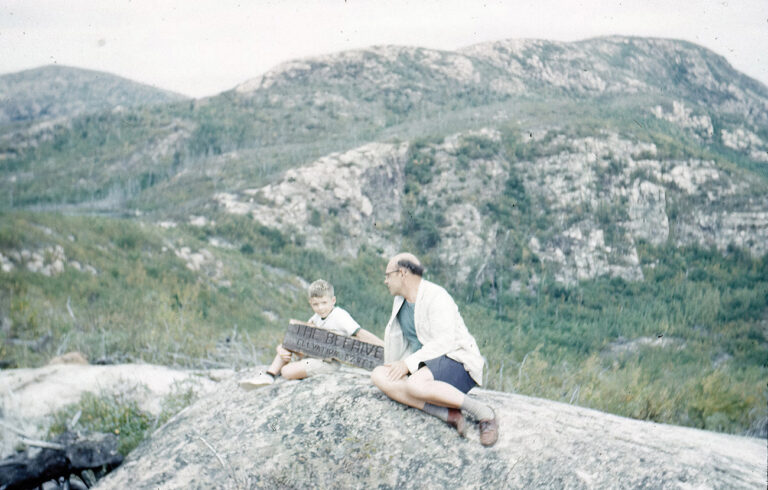

Monat’s passion for the aquatic life began in his early childhood. When I ask him about his first underwater experience, he tells me that he remembers ducking his head underwater at a neighborhood pool and thinking, “Oh my God! This is it!” “I didn’t have a TV growing up,” he continues, “but a friend of mine had a TV, and I’d seen a couple of Jacques Cousteau shows and I was like, ‘Holy moly, I’m going to be a diver when I grow up.’ I knew right off the bat that was where I was going.” When he was 10 years old, he began spearfishing for flounder. Two years later, his stepfather taught him how to lobster, and Monat began hauling by hand in his own skiff. By the time he was sixteen, he had taken over the family lobstering business and had also begun scuba diving to recover ghost gear. “I didn’t have all the fancy rigging,” he tells me. “When I first started diving, I bought a regulator for ten dollars at a yard sale and tore it apart, rebuilt it, made it work.”

As he begins to talk about his childhood, he walks over to a shelf piled with papers and pulls out a booklet of cartoons about his life drawn by his wife, Edna, as a complement to a presentation Monat gave to the Mount Desert Island Bar Harbor Rotary. The booklet is called Diver Ed’s Story—Master & Commander, League of Underwater Superheroes, and he flips open to the first page and points to a cartoon of a brightly painted skiff. “My stepfather was Portuguese,” he says, “so that’s what my skiff looked like—every plank was a different color.” As he talks, he taps his fingers on the yellow, orange, blue, green and red planks of the cartoon skiff. “Everything in my life was like that,” he says. “Everything was that colorful.” The handle of his stepfather’s hammer, Monat says, was hand-painted with bright alternating stripes of colors all the way around its wooden base. Later during our conversation, Monat describes the diving school that he and Edna plan to build this summer where their garage now stands: “It’s not going to look like anything around here,” he says. “It’s going to be full of bright colors.” The school won’t just stand out visually among the gray-shingled New Englanders that line Monat’s street; it will also be the physical manifestation of the diving community that Monat has spent the last two decades building—a community that was virtually nonexistent before he moved to Downeast Maine 25 years ago as a student to attend Bar Harbor’s College of the Atlantic.

In his first year at College of the Atlantic, Monat took an outreach education class. Through the resources of the college’s “Whales on Wheels” program, Monat began carting around a minke whale skeleton and a Naugahyde leather pilot whale to local area schools and libraries, beginning, in effect, the educational strand of his multifaceted career. He eventually began running a program that featured a

“A friend of mine had a TV, and I’d seen a couple of Jacques Cousteau shows and I was like, ‘Holy moly, I’m going to be a diver when I grow up.’ ”

travel ing touch-tank instead of whale skeletons, which he continued to present even after his college graduation. It’s not that he doesn’t like marine mammals, he tells me, but because he grew up fishing and diving, he recognized early on in his educational endeavors that he was just “more into invertebrates.” For his final project at College of the Atlantic, Monat built an underwater nature trail in Frenchman Bay, which took him three years to complete. The Smithsonian heard about his project and hired him to help with their Gulf of Maine installation at the Natural History Museum after his graduation.

His life before, during, and after his time at College of the Atlantic, from what I gather from a whirlwind verbal tour of Monat’s adventures both below and above the surface, included diving for scallops, urchins, sea cucumbers, and sand dollars, harvesting periwinkles that were trucked down to Machias and processed in France and whelks that were shipped to California, inshore and offshore lobstering, scallop dragging, fish trawling, commercial diving, underwater construction and repairs, and search and recovery—followed by postgraduation stints as a marine ecologist, videographer, and scuba instructor. His urchin-diving tales are particularly colorful. “You’d come up, the next set of tanks would be ready, you’d open your mouth and put in a handful of baked beans and back down to the bottom. That was my life for quite a while, just like that.” When the other fisheries became restricted, Monat shifted primarily to scalloping, and dove alone for a number of seasons. “I’d call Edna between dives,” he says, “just to let her know I was alive . . . I liked the challenge of it.”

One of Monat’s biggest projects now is the Dive-In Theater, a two-hour boat ride on the r/v starfish enterprise through Acadia National Park that includes an onboard touch-tank for passengers. The Dive-In Theater, which began running programs in 2000, was the “natural evolution” of his experiences at College of the Atlantic, and is a particular reflection of Monat’s passion for invertebrates that guided his earliest foray into education through his traveling touch-tank program. Monat still scallops in the winter when the starfish enterprise isn’t running programs. “People ask me what I do,” he says, “and it’s like, ‘Well, I do the Dive-In Theater, I teach scuba diving, I do commercial work, we go scallop diving, we do dive charters, teach classes—pretty much anything underwater . . . it’s kind of . . . it’s a little . . .” He pauses, as if to say, “It’s a little crazy,” and then continues: “Well, that’s Maine. If you don’t want a real job, that’s what you do.”

Aboard the starfish enterprise, Monat transforms into Diver Ed, an underwater superhero who dons a black -and-red wetsuit adorned with a giant “D” and “E” across his chest. The ironically named Captain Evil, known on dry land as Edna, Monat’s wife, drives the boat and narrates the trip, which begins in earnest after Edna drops anchor and Diver Ed is pushed overboard by several of his passengers—usually the younger ones—into the waters of Frenchman Bay. Edna is a licensed Coast Guard captain, trained child psychologist, naturalist, and the backbone, Monat says, of the whole operation. Monat films what he finds below the surface with a high definition, National Geographic–style camera that projects the images in real-time back to a large screen on the boat, trading banters with Edna through a built-in microphone on his dive mask. Monat is always accompanied by his small plastic sidekick, Mini Ed, a figurine decked out in dive gear who provides a Playmobil sense of proportion for the animal and plant life encountered below. When Monat and Mini Ed return to the surface, they come bearing creatures—sea cucumbers, sea stars, rock crabs—that passengers can observe and gently handle before Monat drops them back overboard. It’s this dual experience of showing people sea life in its natural habitat and giving them the chance to observe it closely on the boat that seems to most excite Monat—and his passengers.

The spring and summer are the busiest times for the starfish enterprise, with the boat generally running at least two trips a day until August, when a third daily trip is added to the schedule. Most of the trips in the spring are school groups, and then toward summer and fall, the boat often runs trips for private parties, weddings, and lobster bakes. The boat was purposefully designed with varying bolt patterns on the deck to accommodate different seating arrangements—and the possibility of clearing the deck completely to turn the boat into a floating dance-hall party space. There’s a huge slingshot mounted on two posts all the way into the back of the boat—38 feet back, Monat says with a bit of a grin. During parties or lobster bakes, revelers can load potatoes and lobster shells into the slingshot and catapult them “all the way out to sea. It’s wicked fun,” Monat says, and I think how true it is that Monat’s programs are hands-on learning in the most complete sense of the expression, simple machine demonstrations and all.

When I ask Monat what he most hopes to accomplish with the Dive-In Theater, his answer is immediate: “What we’re trying to do is fascinate people.” To illustrate, he starts stacking a little pile of gold foil–wrapped chocolate coins on the table in front of us. “Say you look at this on the bottom. And here you are, swimming along, like this”—he pauses to make a swimming motion with his hands above the pile of chocolate coins—“and there’s just a million of them all. Let’s say these are sand dollars right here,” he says, and he drops a chocolate coin on the table, and then another, and then another. “You’re just kind of swimming over them,” he continues, “thinking, ‘Oh sand dollars, whatever.’ But I want people to stop and look at them.” Monat starts talking faster, and the questions flow quickly. “What are they doing? Are they moving around? Are they trying to feed? What’s going on? Can you see the tube feet? With the Dive-In Theater, the plan was ‘Okay, I’m going to stop and force people to see all this stuff that I want them to look at.’

“I have this weird disease,” Monat says. “I look at water and I want to know what’s underneath there. I see water and I can see the bottom. That’s my life, right. I can drive by different places, and to me it’s like a three-dimensional world, but to everyone else it’s just . . . ” He trails off for a moment. “You go to the Caribbean,” he starts again—“and I love the Caribbean—it’s beautiful, and there’s tons to see, but it’s a lot more predictable. It’s like diving in an aquarium. You’re not allowed to touch anything or take pictures or video. Which is fine. But I’m a hands-on kind of guy, and part of the reason this whole thing works is because it’s not just the video part of it. It’s all those little kids sitting there holding this stuff going, ‘Hm.’ And then, the best part is when the kids from COA come up and say, ‘Oh, I was on your boat when I was twelve, and I just wanted to be a marine biologist, and now I’m at COA.’ It’s stuff like that that makes me feel like we’re really doing what we need to do.

“My problem,” Monat says, “is that I’m really concerned about a lot of different things that are going on underwater and in the world.” Monat pauses. He’s not political, he clarifies, and it is clear from the way he talks and the passion in his voice that yes, his primary agenda is simply to share his curiosity about the primordial strangeness of the sea and the fantastical creatures he spends most of his waking life in contact with. “What I’m hoping,” he says, “is that I can help make people want to do something.

“Remember that one little kid who came to the Dive-In Theater?” Monat calls out to Edna, who is standing in the kitchen. “Remember how he said, ‘This has got everything! It’s got action, adventure . . . ’ What’d he say?”

Edna walks into the living room, smiling at the memory. “We were on a park ranger trip,” she begins, “so it was not even the most interactive trip we’ve ever had, but this little kid just suddenly leaped out of his seat and said, ‘It’s got everything! Love, sex, romance, danger!’ ” We all laugh, and I think, “Well, that’s not something you hear during most science lessons in school.”

“All that stuff is so interesting and fascinating, even for us,” Monat says. “Some people might think, ‘Oh, you must be bored, seeing the same things every day,’ but it’s not like that for us. Literally, this past year there was an, ‘Oh my God!’ moment every time we got in the water.”

Edna nods. “There are so many changes in the bottom,” she says. “You just never know what’s going to happen. You think you know where you’re going, you think you know what you’re going to see when you get down there, but . . .”

Monat picks up when she trails off. “Every time you stop and look at something, it’s like, ‘Am I seeing something completely different than what I saw before?’ Think about how many people in Maine make their living from the ocean. Think about the number of different species we harvest here. The reality of it is that it is an amazing place, and it has such an amazing ability to recover. There’s a ton of marine life here and a lot to see. I’m glad there isn’t even more diversity because the trip’s long enough as it is—it’d be a four-hour trip otherwise.”

Monat tells me he’s been thinking about getting a bigger tank system so he can dive deeper on future trips—currently, his dives average between 50 and 80 feet, with the occasional dive reaching 110 feet. On one dive last year, he got his hand stuck in a hole with a giant lobster, and ended up running out of air. “It was a long way to the surface once

I finally got my hand out,” he laughs, before turning ever so slightly serious. “So I’ve been thinking about getting a bigger rig.” Edna has left the living room by this point, but I can hear her laugh when Monat tells me that she is the biggest impediment to upgrading to a larger system: “Edna says, ‘No, you’ll never come up,’ ” he says, and after listening to Monat articulate his love for everything from nudibranchs to blood stars, I wonder if she might just have a point.

“One time,” Monat begins, launching into another story about life below the surface, “I was filming a big female lobster and a big male lobster and they were in the same hole, right. And we knew what was going on—he was waiting for her to molt. And meanwhile, while I’m doing that I had two giant lobsters coming up and attacking me because I was in the way of the hole and they wanted to get in there too.

“It’s a madhouse down there,” Monat exclaims, and Edna chuckles from the other room. “People don’t realize it.”

In Silent Spring, Rachel Carson writes, “One way to open your eyes is to ask yourself, ‘What if I had never seen this before? What if I knew I would never see it again?’ ” In spite of his levity—or perhaps, more aptly put, in addition to it—Monat’s work revolves around a deep sense of purpose, presenting a significant and engaging challenge to everyone who comes aboard the starfish enterprise, in between jokes about how sea cucumbers breathe through their anuses and how Mini Ed has fallen in love with yet another lobster who doesn’t love him back: to open our eyes and look, and then look again, and in the looking, to remember that one of our greatest human gifts is the capacity for fascination.