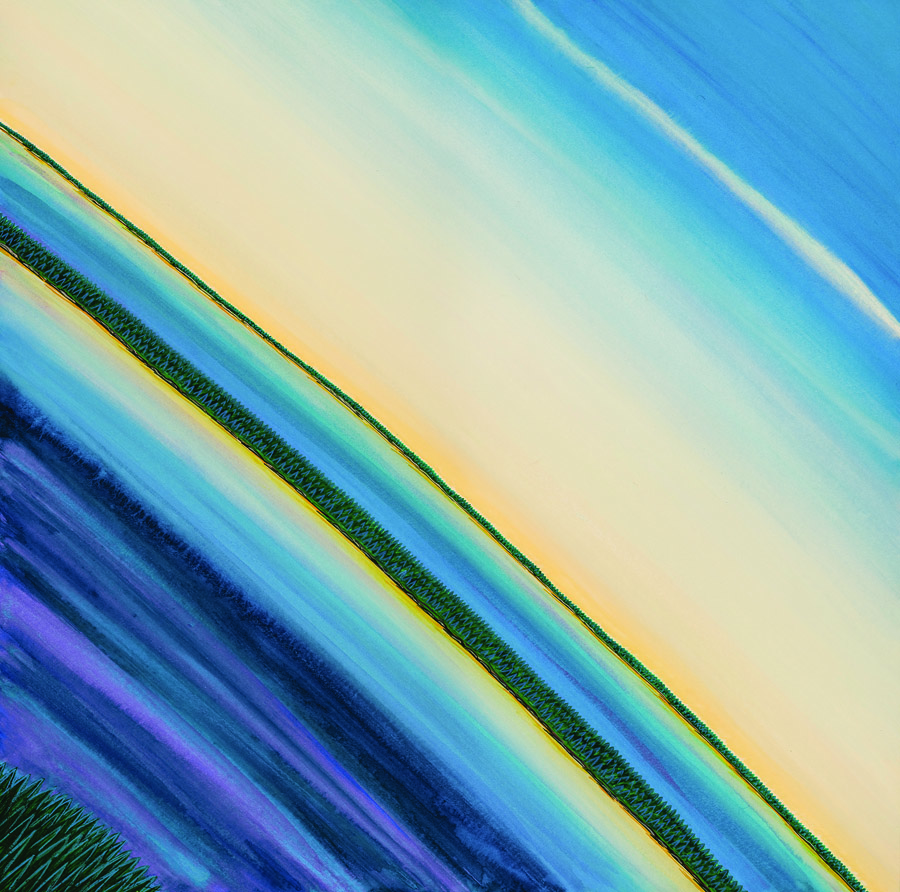

It was already late afternoon when Eric Hopkins picked us up in his boat at Gotts Island for the trip to his studio on North Haven. Eric knows how to look at islands. And we were on our way to look with him. There, represented in oils, we would see oceans and islands viewed from the air, from the sea, and from great distance. The angles were strange and marvelous. Islands we thought we knew were transformed.

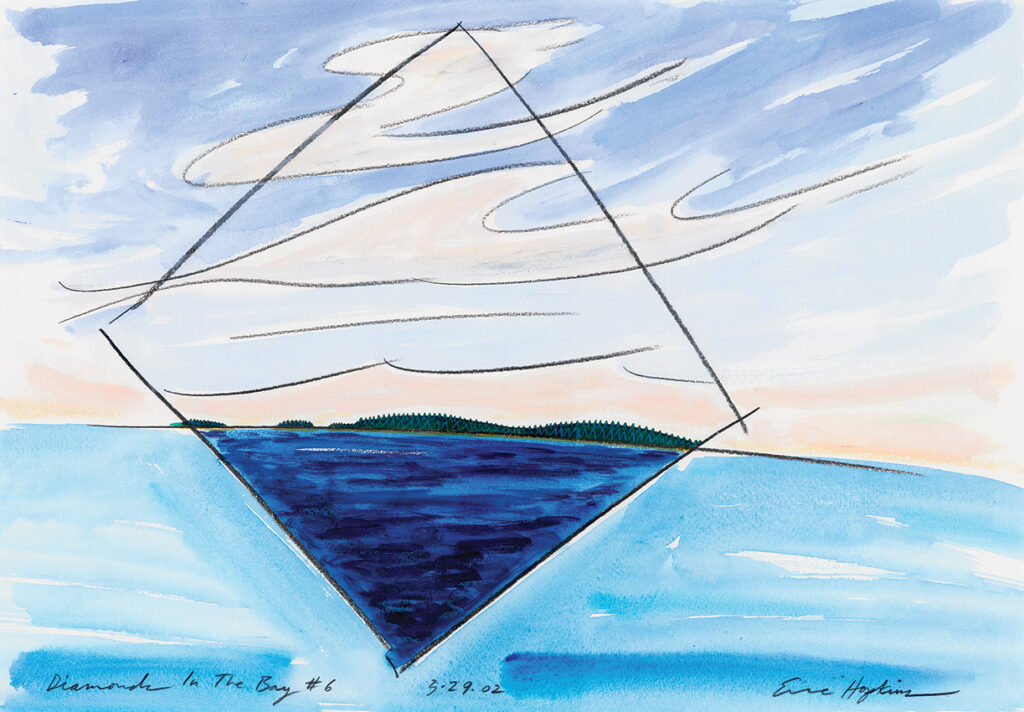

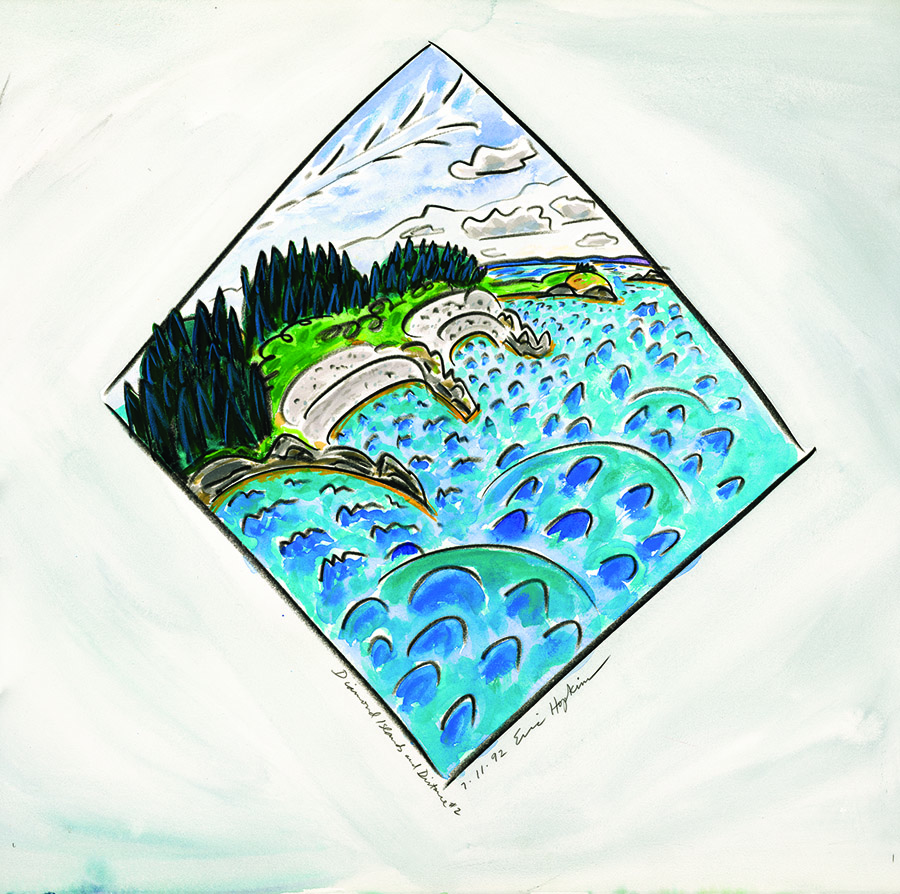

To celebrate his recent retirement, and well aware of our many years as summer residents on Gotts, my husband’s colleagues had given him a gift certificate for one of Eric’s paintings. Our challenge now was to make a choice. After much discussion, much to-ing and fro-ing, from painting to painting, we had settled on a watercolor in which Eric had superimposed an abstracted diamond shape on streaks of pale blue ocean. The diamond looked like a lens focused on mere dots in the distance. The dots of course were small islands.

Now, well-wrapped painting in hand and anticipating its appearance in our Gotts Island house, we were back on Eric’s boat, heading home. Soft early evening light still suffused the sky and the ocean, but we knew that even with a fast boat, it would be full dark before we reached Gotts.

Eric didn’t seem to mind that. He was talking about how we view islands on the surface of the ocean. It was, he said, a matter of focus. In a gesture suggesting the image he had created in our painting, he traced with his hands a diamond-shaped lens. He was giving us, literally, a hands-on lesson in perception.

Eric is the descendant of generations of island people. In thinking later of our experience that evening on his boat, I was reminded of another island artist, the Finnish writer Tove Jansson, who provided, in Summer Book, a similar lesson in perception. A chapter of that book was excerpted in Vol. 30 (2014) of Island Journal.

In a series of short pieces drawn from her own island experience, Jansson wrote of a different ocean, in a different country; but the connection with Eric and Maine’s islands is abundantly clear. It was as if this writer and visual artist, who died at age 87 in 2001, were with us on the boat, nodding in agreement as Eric talked.

“Yes, I know about that,” she might have said. “I too have used my hands as a lens in order to see those far-off islands. It’s what people who know islands do.”

Eric uses paint and canvas to guide us in looking at islands and the sea; Jansson used language. In Summer Book a fictive grandmother, exploring her island home with her young granddaughter, raises her arm so that she can see below the sleeve of her sweater “a triangle of sky, sea and sand–quite a small triangle.” The view stretches outward, toward a far-off neck of land, but encompasses the sand of the beach in the near distance.

Tove Jansson lived for years on a summer island far out in the Finnish archipelago; she knew about motion and movement in the islanded landscape and its surrounding sea.

As we would expect, too, from a writer who was also a painter and the famous creator of the Moomin cartoons, she understood scale and perspective—the old woman sees that the blade of grass and the down are “at precisely the right distance for her eyes”—and what the eye yields to those who pay attention.

Here in Summer Book, for a brief moment, Jansson freezes, through the eye of the grandmother, a vision that includes at the same time both the broad expanse of sea and sky, a miniscule bit of seabird down, a tiny blade of grass growing in the sand, and finally, in the trick of the eye, a small piece of bark that “if you looked at it for a long time … grew and became an ancient mountain.”

The snapshot is complete when the old woman raises herself with difficulty from the ground where she has been sitting, and the fleck of down, so carefully observed, is carried away, in a light morning breeze, toward the horizon.

“The big events always take place far out in the skerries,” Jansson observes in another vignette from Summer Book. But of course, she suggests, it doesn’t matter if “only small things happen in among the islands” because the small becomes the large.

It’s all about scale: what, I wondered, is small and what large? As increasing darkness and the boat’s eastward motion gradually transformed the world we were moving through, Eric, like Tove Jansson, was explaining to us how small things, like small islands, enlarge our perception of the miniscule and the distant.

And even as he spoke, Gotts Island, once a dot in the distance, was becoming larger, a darker mass on the calm water. Soon the jagged profile of spruce against the night sky told us we were almost home.

It seemed only moments until we were standing on the stony “back of the beach” at Gotts, clutching the painting that shows us how to look at islands. From the shore we watched Eric turn the boat back toward North Haven. Soon it was a mere speck in the nighttime sea.

The watercolor we chose that day, with its pale blue sea and abstracted lens-like diamond, has now hung for almost 20 years above the fireplace in our Gotts Island house. It reminds me of our wonderful evening journey with Eric, and also of the old grandmother on an island in the Finnish archipelago who watched a tiny wisp disappear in the distance.

I look again and again at the islands that Eric painted as minute green specks in the lens. Against a field of pale blue sea and sky, I think they have become larger.

See more of Eric Hopkins work at www.EricHopkins.com

Christina Marsden Gillis lives in Berkeley, California but has spent almost every summer of her adult life on Gotts Island. She is the author of two collections of island-themed essays, Writing on Stone: Scenes from a Maine Island Life, and Where Edges Don’t Hold. Her writing on island experience has also appeared in numerous journals.