Not one of the lands written into your destiny will speak to you the language of your first atlas.

—from “The First Atlas,” a poem by Primo Levi

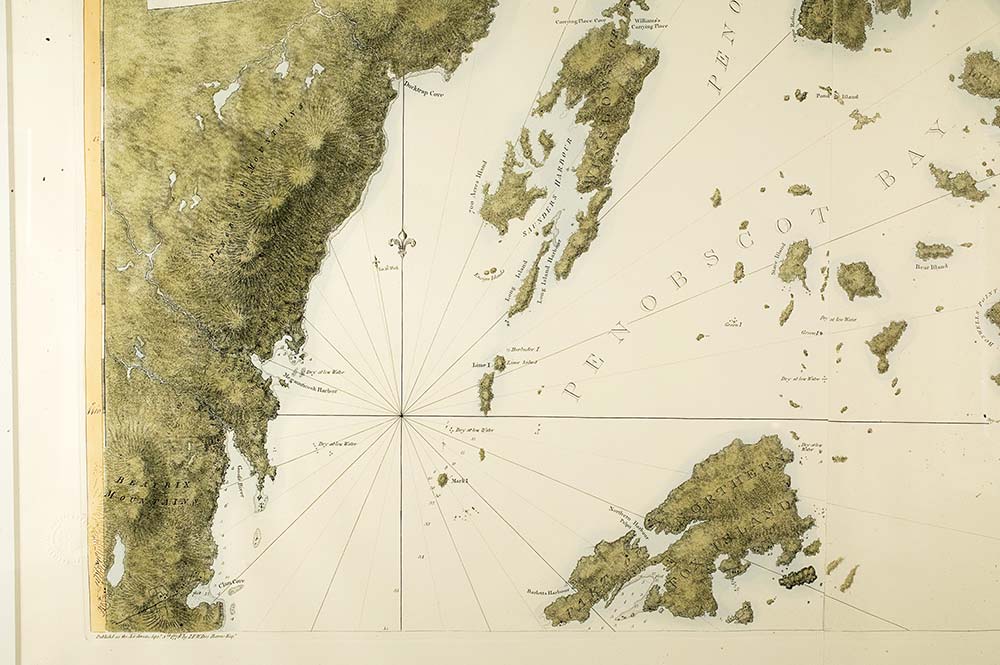

On April 13, the printing presses producing traditional paper nautical charts permanently closed down at NOAA’s Office of Coast Survey. Demand had plummeted. Budgetary urgencies had escalated. Paper charts are no longer the mysterious, ubiquitous, and powerful tools they once were. Chart plotters, tablets, and smartphones have officially become the first atlas for everyone at sea who is in need of a reference beyond their own memory and the evidence of their senses. Coastal mariners, islanders, and all who venture to sea have crossed a historic threshold.

How does it feel?

I mull over the question, and a kaleidoscope of countless experiences come to mind, all sharing one trait: For 40 years paper charts have helped me to see where I am, for better (mostly) or worse (occasionally).

Sometimes the news was good, like when an Outward Bound student navigator looked up from a sodden chart with a smile, finally fully confident which shore our open boat was approaching in the Mussel Ridge channel. Our vessel’s geographic and existential crisis was over. Sometimes the paper chart news was not so good, like when my wife (a new sailor at the time) and I ran a wooden boat aground on our honeymoon sail, and the best I could do was say, “Looks like we’ve hit Trial Point Ledge.”

For other mariners, the orientation provided by paper charts has been undeniably rich. Think of just one sector of human experience at sea—the military. Over 100 million paper charts were printed for the Allied Forces in World War II. What plans, fears, and tangles did those charts reveal? Consider the countless notes and layers of information paper charts have recorded. Penciled lines, headings, and distances mixed with stains of dropped food, sweat, and blood, mixed with the chart marginalia noting good fishing spots, wreck entanglements, and hidden harbors of refuge. All contained within that rectangular paper frame of golden proportions, a merger of art and science and life. Who could imagine that any navigational tool could be more engaging and compelling than these charts?

Turns out, the answer is “Most of us.” We’re all jumping ship, from charts-on-paper to charts-on-screens. And the new tools we’re now using are even more bewitching, useful, and orienting than the old paper ones. So compelling, I’d venture to say, that they’ve lured some people away from the sea itself. Many have left the territory, and only travel within the map on the screen. We’re becoming navigators who always stay belowdecks, helmsmen and -women who look in at the plotter more than we look out at the sea.

What started with the first computer map in 1950—a weather map—has led to an eventual explosion of .pdf, .kmz, .gpx, and other digital formats and pipelines for delivering cartographic data on-screen. And the largest mass communicator on the planet, Google, is fast weighing in with even more data and experience.

I take some comfort in all of these new developments and additions, since I am of the belief that we are bewitched by screens for some vitally important reason, even if I’m not always comfortable or certain why I’m spending so much time belowdecks. Perhaps the secret of that motivation, now locked deep within our genome, will be revealed when and if we humans step up and successfully draw on all this data and communicative capacity to solve some of the challenges in front of us, like making our way through the Maine fog, or figuring out a healthy course through the Anthropocene.

In this spirit, allow me to share a few things I’ve learned recently about Google Ocean, a relatively new “layer” in the popular application called Google Earth.

My first big exposure to Google Ocean was at an ocean film festival in California, where my production company had a film in competition. Early one morning, I was walking around the empty industry exhibit hall with a cup of tea. Google Ocean, in concert with Sylvia Earle’s fantastic Mission Blue, was an exhibitor. They had set up three enormous screens in the shape of an alcove into which you could walk and stand behind a central pedestal with a joystick.

A solitary man, whom I recognized as the explorer Bob Ballard, quietly walked up to the pedestal to take control. I wondered where within the world’s oceans he would navigate, so I entered the alcove, said hello, and stood behind him. Maybe we’d revisit the site in the North Atlantic where he found the Titanic? Or perhaps the South Pacific site where he visited John Kennedy’s sunken PT-109? Or the Black Sea, where he discovered seafloor evidence of Noah’s flood? No, in fact. Bob Ballard visited his home in New England, to see if the high-resolution data from the most recent satellite pass would allow him to individually identify one of his horses.

The lure of familiar landscapes is very strong, and perhaps he had been on the road for a while. But all that is another story. The point is, when Ballard finally yielded the joystick and left, I was soon diving 400 feet into Penobscot Bay, moving across the seafloor as freely as a dolphin or a beaked whale, or whatever might naturally swim those waters. I swooped up over ridges and plunged down into sunken canyons.

This was not just numerical depth soundings and shadings on the navigational paper charts of old, with the occasional abbreviated three-letter statements of seafloor mud. This was a visceral, giddy, almost carnival-like experience, moving below and above the sea.

On the surface, I came upon a floating ocean data buoy. Whoa. I stopped. Standing in that alcove across the continent from my home, I knew sea surface temperatures, wind speeds, and wind directions, right at that moment in Penobscot Bay.

Quickly heading south to Antarctica, I went 100 years back in time to follow Ernest Shackleton’s epic voyage, then back to the present and the warm waters off Baja where I swam alongside a whale shark, whose actual course last month had been recorded and uploaded by a position tag fixed to its back (ouch).

In that moment, I saw and felt the allure of this power in the waters well beyond the navigators of days gone by. Visceral variety through time and space is Google Ocean’s magic, a repository for a huge and growing range of observation and experience. Once available only to marine specialists, it is now integrated and available to everyone. Somewhere, no doubt, someone is already programming the next generation of chart plotters.

Last month, opening Google Ocean at my home in the Midcoast, I decided to venture deeper, and visited the waters off the Yucatan Peninsula, where the Schmidt Ocean Institute recently mapped the cause of the demise of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. No one had ever done detailed maps of the crater left by the giant meteor that supposedly did the dirty deed, because the only part of the crater that is accessible is underwater.

But now, the 4,000-foot underwater cliffs have been exposed via hull-mounted multi-beam sensors. You can see the cliffs yourself (as well as take a tour of the high-tech vessel R/V FALKOR, which collected the data) on Google Ocean.

On another track, scuba divers from the Catlin Seaview Survey are swimming about the world’s coral reefs with a weird-looking camera, acquiring and adding underwater 360-degree photos to Google Ocean. This is truly navigation of an altogether different sort.

Closer to home, in the Gulf of Maine, we are also aware of how little we know. Because I’ve had the chance to spend time with ocean folks, I’ve heard that statistic about the ocean covering 70 percent of the Earth (almost always followed by the other statistic—that we know only 5 percent of the ocean) about a zillion times. But the meaning of these numbers struck home clearly when I was looking at the details of what had been mapped by boat or plane or satellite in our own waters. Surprise! There is a place in our near neighborhood, 10 miles wide by 10 miles long, which is a complete blank. Seriously; at 43.781N latitude, 067.59W longitude, there is 100 square miles of mystery. Nothing. I felt like I was discovering an extra row of seats in my car that I never knew were there.

So, buoyed by all this new knowledge, I’m ready to let go of the paper charts in the day-to-day life at sea, as long as I can spend time on deck at sea, especially in the early dawn hours. And yes, the old charts will always hold a place in my heart and memory, as the language of my first atlas. I have framed them for my walls. But if the lands of our destiny require the use of a new atlas for today, and an even newer atlas for tomorrow, so be it. Dragons and all. I’ll be as ready as I can to stand watch.

David Conover is a filmmaker, a resident of Camden, and a caretaker of the Curtis Island lighthouse.