What follows is adapted from Abigail Trafford’s memoir, High Time (Tide Pool Press, 2023). Trafford, whose career included reporting, writing, and editing at The Washington Post and U.S. News & World Report, has come to the multi-generational family retreat at the north end of Vinalhaven her entire life. The author of several books, she now explores the not-so-charmed life that often was the baggage she brought to the island and untangles the extended family’s impact on her, and on her siblings, children, and grandchildren. The circle of family, living and dead, dominates the pages and in the end, Trafford comes to understand, forgive, and find peace.

More than 100 years ago, my grandparents built a house on an island in Maine, providing a shared haven for future generations in the timelessness of sunsets and tides. A century later, it is the place that holds a disparate family together. Several cousins, including myself, have built little houses around the “Big House,” the way planets surround the sun.

Psychologists talk about “object permanence” as the key to personal development. It is based on a toddler’s shorthand: when Mommy leaves the room, she hasn’t disappeared off the planet but will come back again. It is a pillar of trust and stability. In a way I have applied this theory to a place. In a digital world of scattered families, the island is like Shakespeare’s ever-fixed mark, that looks on Nor’easters and is never shaken. It is the beacon to all my wandering. Vinalhaven has been my lifelong refuge no matter how far I roamed…

I AM THREE YEARS OLD. We are having a picnic. Aunt Ruth gives me a job: take the wartime bag of white margarine with the bright orange dot and squish it all around until the margarine is yellow like butter. The big cousins race around by the shore. The fathers are all away at the War. I squish and squish. Finally, the bag is yellow. Aunt Ruth takes me in her arms. I am so happy. I am safe.

I AM NINE. All the cousins are putting on a play. In this murder mystery, I am the wife of the victim—and the killer. I wear grown-up clothes from the costume box in the attic, a fur scarf around my neck, a huge hat with feathers, bright red lipstick. When the inspector asks: “Why did you murder your husband?” Pause as instructed, glance at the audience, lick lips, reply: “Because he was so boring!”

My parents had started out on a story-book life. My father, a Harvard lawyer and composer, my mother a sculptor and pilot. They both played the piano, and I grew up with two grand pianos in the living room. But World War II crushed them both. My mother suffered miscarriages and gave birth to a baby girl who died. She sank into depression and underwent draconian therapies of shock treatments and various drugs. She never recovered. My father, a lieutenant in the Ninth Infantry Division, fought on the front lines across Europe and brought home a combat creed of fatalism.

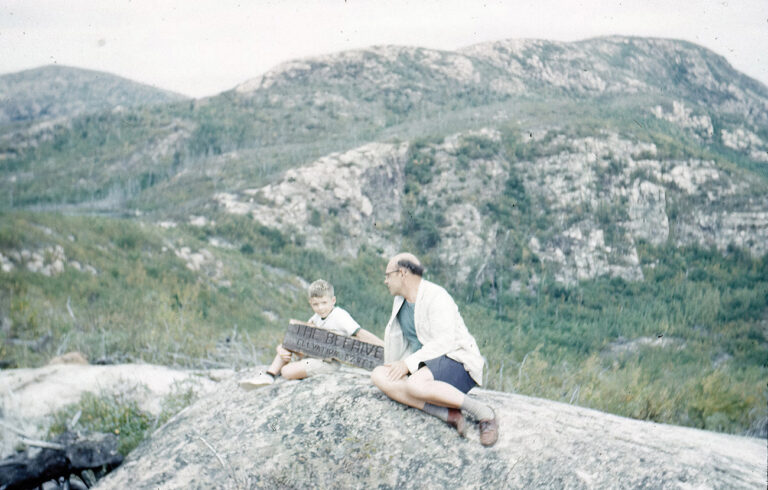

near the “Big House” on the Fox Islands Thoroughfare.

I AM TWELVE. Aunt Ruth and Aunt Polly are running the Big House. Cousin Perry and I are cool and naughty. We smoke sweet fern—baking it in the oven and puffing on corn-cob pipes like gangsters. By this time, my younger sister and I have stopped noticing the absence of our mother. We are used to being farmed out to aunts and grandmothers.

I AM SIXTEEN. Daddy has asked me to crew in the dinghy race. Floorboards swash in seawater as we head down to the starting line. He recites “Barbara Fritchie”: “Shoot, if you must, this old gray head, But spare your country’s flag, she said.” BANG, we’re off. My job: Lean. Bail. Pull up the centerboard. Push down the centerboard. Look for rocks. Do the impossible! Daddy is our lieutenant. I’m in E Company and we are on the front lines. Going to tack, he yells. Head down. Once more unto the breach!

I grew up with privilege: the right schools, the right families, summers in Maine. And I grew up deprived: no regular meals, no new clothes, no mother. The family was drowning in medical bills. I went to school on partial scholarships. I bolted to escape a childhood shadowed by mental illness. I wanted to be other. Yet, I have always brought the island in Maine with me, wherever I wandered.

I am a paradox: a bolter with roots. Sometimes I am forced to bolt. Other times I choose to bolt. The more I bolt, the stronger the pull of the island becomes. This back and forth, insider-outsider/outsider-insider motion is in constant tension, always ruffling the status quo.

I AM TWENTY-THREE. Terrified. Thrilled. I am getting married. My father walks me down the aisle of the North Haven Church. My mother is at the Brattleboro Retreat, a private mental/addictions hospital in Vermont. My guardian Aunt Ruth has died. My Aunt Lindy puts on the wedding. She picks out a wedding dress and adds a lovely lace veil from a great-grandmother. Granny wears a stylish pale green brocade outfit. Mother-in-law wears beige lace and wishes her son had chosen any one of the bridesmaids to marry instead of me.

I AM THIRTY-SIX. Broke and broken. Single mom with two small children. Aunt Lindy and Uncle Arthur invite us to the island. They now own the Big House. Aunt Lindy takes my daughters into her bedroom. She wears an eye patch—they call her Grandy-Patch. They have tea parties together—the way I used to do with Granny. I stay in bed in the Blue Room and read War and Peace. Living in Washington, D.C., working fulltime in a newsroom, raising a family, flying solo, head down, doing the impossible…is exhausting.

It turns out that a chaotic childhood is good preparation for a career in journalism. Writing is creating copy out of chaos, finding words to bring order in a disordered world. In Houston, I covered the Apollo moon landing program. Often I was the only woman at a press conference. I moved to Washington and worked for U.S. News & World Report, becoming the first (and only) female assistant managing editor.

I AM FIFTY-TWO. Long remarried to Don, my beloved, hard-drinking—Tanqueray martini on the rocks—foreign correspondent. We are on the banks of the Nile. A felucca is sailing by, and I am drawing the scene. Don points out that instead of the felucca, I am drawing a North Haven dinghy. Instead of pyramids, the Camden Hills! “That house you talk about,” he says: “You have to build it.” And so, we do. Cousin Perry builds us a shingled post-and-beam house in a field. Our dream: to “retire” to the island and write books. Yet dreams shift in shifting winds.

Don Neff had been with Time magazine. He wrote books about the Middle East. In 1986, I moved to the Washington Post as health editor and columnist. Don and I traveled together, wrote together, and slowly shifted our sights to Maine.

IN 1993 I WROTE an essay about the “WASP Rot” syndrome, a downward malaise accelerated by depression, alcoholism, and wayward marriages, where the Noblesse Oblige of ancestors had morphed into a kind of Faiblesse Oblige. In the article, I was tough on George H.W. Bush, who had just lost the election to Bill Clinton: “He may defy the WASP Rot label with his impressive resume, but he kept gagging on the silver spoon in his mouth.”

But there is another, more enduring story about George H.W. Bush, the last of the presidents to have fought in World War II, whose family had also sought refuge on the Maine coast.

In 1990, the White House invited health reporters into the Roosevelt Room to talk about health and fitness with the President. Health care reform was heating up as a political issue. President Bush had directed his Secretary of Health and Human Services to study three pressing problems in health care: at the time, roughly 37 million Americans lacked health insurance; medical costs were skyrocketing; and about nine million Americans, the elderly as well as children, needed nursing home and other supportive services.

The discussion began with a question about daily exercise, and then turned to “harder” issues of whether access to health care coverage was a basic right. I asked if he would put money into an initiative to provide insurance to all Americans. His press secretary interrupted with a snarl: “Washington Post! Trick question, Mr. President.” Suddenly the president exploded. He raged at me. He was over-the-top furious. Invective poured out of his mouth. He wouldn’t stop.

I was stunned. My first thought was: Oh god. The President of the United States has lost it. He has his finger on the button. He’s in trouble. The country is in trouble. An awkward pause followed. Rephrase the question. It was clear the President hadn’t been well briefed on health care issues—issues that would dominate the presidential race in 1992, which he would lose.

After the conference broke up, I was so shaken I stood apart from the group to gather my thoughts. President Bush started towards me. His press secretary called him back, but the President ignored him. Then he pulled me aside.

“I apologize for jumping on you like that,” he said.

I apologize.

This is not what presidents usually say to reporters. In that moment, I was relieved; the President was back in control of himself.

Maybe Bush was just a savvy politician mollifying a reporter. Or maybe he was who he was: a gentleman.

Noblesse is not about identity. It is about behavior. I tell my children that WASP Rot has been good for us. It forces us to start anew.

I AM SEVENTY-SEVEN. On my own. I’ve aged out of the newsroom at The Washington Post. I spend months on Vinalhaven every year. When my daughter Abbie got married, she went down the path to the motorboat that took the wedding party out to the lighthouse where she said her vows. When my daughter Toria got married, she walked up the path to the Big House, while Cousin Jim played a march composed by her grandfather. Now in the mornings, I sit on a rock and watch my grandchildren run down to the dock. They have sleepovers in the Big House with their cousins. Toria tells them there’s a ghost in the Pink Room.

IN 2020, GRANDDAUGHTERS Sophia, 20, and Lila, 18, take a COVID “year out” of school and pile into our house in the field. We grow lettuce and kale and basil and tomatoes. We plant flowers: asters and zinnias, but the wily deer bite off the sunflower blossoms. No one enters the house except family. We are vigilant and quietly afraid. Lives interrupted. All future unknown. Everything changed with COVID. Except the tides and the proliferating thistles on the shore. A pheasant settles in our field. Grandson Brooks, 21, who is taking courses remotely from his bedroom in Portland, writes a COVID poem:

How did things get this way?

A million small queries

Of how we could do better.

In Italy, corpses pile up in churches.

WHEN THE SNOW BEGINS TO FALL, I am all alone. I am like the hermit monks of old who lived in the desert to seek… what? I watch the tides; smile at the ferry as it passes by at 7:40 in the morning. The snow-capped Camden Hills seem closer. The sky is starker. I can count on the regularity of the ferry, the permanence of the Hills.

A SUMMER OF SILENCES. Few cars on the roads. The sky is bluer, the birds louder. Plenty of spaces in the Downstreet parking lot. Conversations, always brief, are muffled. We turn inward. The rush of summers past is gone. We speak softly and focus on each other. We draw closer.

Afternoons in the warmth of the sun, we have a dance party on our deck for cousin Maudie, 85, who loves to dance. Lila puts on the Oldies play list; the notes blast over the stone wall and out to the Thoroughfare: Twist and Shout! Maudie wiggles her shoulders, like we did last summer, a big smile spreads across her face. Sophia does a cartwheel on the lawn. Will You still need me? Will you still feed me? When I’m Sixty-four.

When I’m Ninety-four? Lila grabs a hula hoop: I Can’t Get No Satisfaction. The ferry goes by. What must the passengers think? Distant figures shouting, twirling, our own kind of Dance Mania, like the distraught poor of the Middles Ages who danced to death to relieve stress?

Hang on Sloopy! Sloopy, Hang on!

My days are full. I write. I jog to the lighthouse. I watch for the ferry to return at 6:16 p.m., all lit up against the dark sky. I look at the stars, the glitter of the universe. I give in to the power of place. After a while, I am no longer all alone by myself. I am not alone. I am with myself. A thin white blanket softens the field. On Jan. 6, rioters break into the Capitol.

AFTER THE BIG HOUSE was built in 1917, the great pandemic of “Spanish Flu” ravaged the planet in 1918. Since then, history has thrown up more wars, Depressions-Recessions, and diseases such as polio and AIDS. Through it all the family place has provided a shared haven in the timelessness of tides and sunsets. Embedded in the landscape is a history of those who came before. And a testament to the power of love.