In September 1816, William King, a politician and businessman in the District of Maine (and at one time, the wealthiest ship owner in the region), was certain that finally, after 30 years of trying to leave Massachusetts, Maine would succeed in getting the votes to become its own state. Voters of the district’s coastal communities would soon cause him to trim his sails, but in that moment of pre-disappointment, he had good reason for optimism.

The outrage among Maine residents toward Boston’s failure to protect the district during the War of 1812 had not cooled, and the numbers from the last vote for independence—held just five months earlier—showed that the votes were there, so King and his colleagues with good reason thought a win was in the bag.

When the vote results were tallied, the separationists did have more votes than those opposed. They didn’t, however, have a 55.5 percent majority, a stipulation required by the state government in Boston for the separation to move forward.

Frustrated that voters in the coastal communities still overwhelmingly voted against leaving Massachusetts, and that they’d be losing statehood over a technicality imposed by Boston, the separationists were desperate. When, four weeks after the district-wide vote was held, delegates of Maine communities met to review the returns and assess next steps, shenanigans ensued.

In an effort to win separation, there were claims that returns from some of the towns were lost; the legality of some votes was questioned (they were “incorrectly” or “illegally” returned or the question on the ballot was not appropriately worded or unqualified voters had voted); debate on what the word “majority” meant concluded in a “truthiness” definition that allowed for some fuzzy math, and voila, the 55.5 percent majority was achieved!

Anti-separationists were apoplectic. The fallout was, as we say in Maine, wicked bad. Massachusetts didn’t buy it, and those who perpetrated the scheme were castigated in the press. After such obvious foul play, the optics were just too bad for Boston leaders to allow separation.

King and his cohorts laid low immediately following the fuzzy math debacle, but he was as determined as ever to bring about Maine’s statehood.

In that September 1816 election, even though there were more votes for separation than not, once again, the biggest number of opponents came from coastal communities where the Coasting Law reigned. If Maine was ever going to become a state, King knew, he had to get more votes from those coastal communities, and there was only one way to crack that nut. The Coasting Law had to go.

~

The Coasting Law had been a problem for separationists since 1789, when Congress passed an “Act for Registering and Clearing Vessels, Regulating the Coasting Trade, and for Other Purposes,” otherwise known by the more succinct Coasting Law. This law required vessels sailing along the Atlantic seaboard to stop at a custom house in each state along the way and pay a fee (both the trip out and the return). Vessels only had to stop and pay the duty in states that didn’t border their originating location.

The only state Maine shares a border with is New Hampshire. Because the district was part of Massachusetts, however, Maine ships didn’t have to stop and pay a fee until reaching New Jersey. This was a big deal for Maine’s coastal communities, said Pulitzer Prize-winning historian (and Maine native) Alan Taylor, author of Liberty Men and Great Proprietors: The Revolutionary Settlement on the Maine Frontier 1760-1820.

Having to pay those fees would be a “significant bite” into anyone’s profit margins, he noted, but especially so for merchants shipping low-value commodities like cord wood—which Maine merchants were exporting a lot of at the time. Plus, it would have been a huge time-suck to make all those stops coming and going. Just like today, the faster something ships, the better.

While the population of Maine’s interior towns steadily grew after the Revolution, the folks on the coast were the ones with the juice, Taylor said. Coastal communities had the highest populations, the most political clout, were most dependent on coastal trade, and had close ties with Massachusetts.

With the Coasting Law in place, folks who lived in Maine’s coastal communities (and those nearby who did a lot of business with them) had zero incentive to jeopardize ties with Massachusetts, he said. The Coasting Law then became the roadblock that held the separationists back. After the 1816 brouhaha settled down, William King, the wealthiest ship owner in the district, set his sights on the federal law.

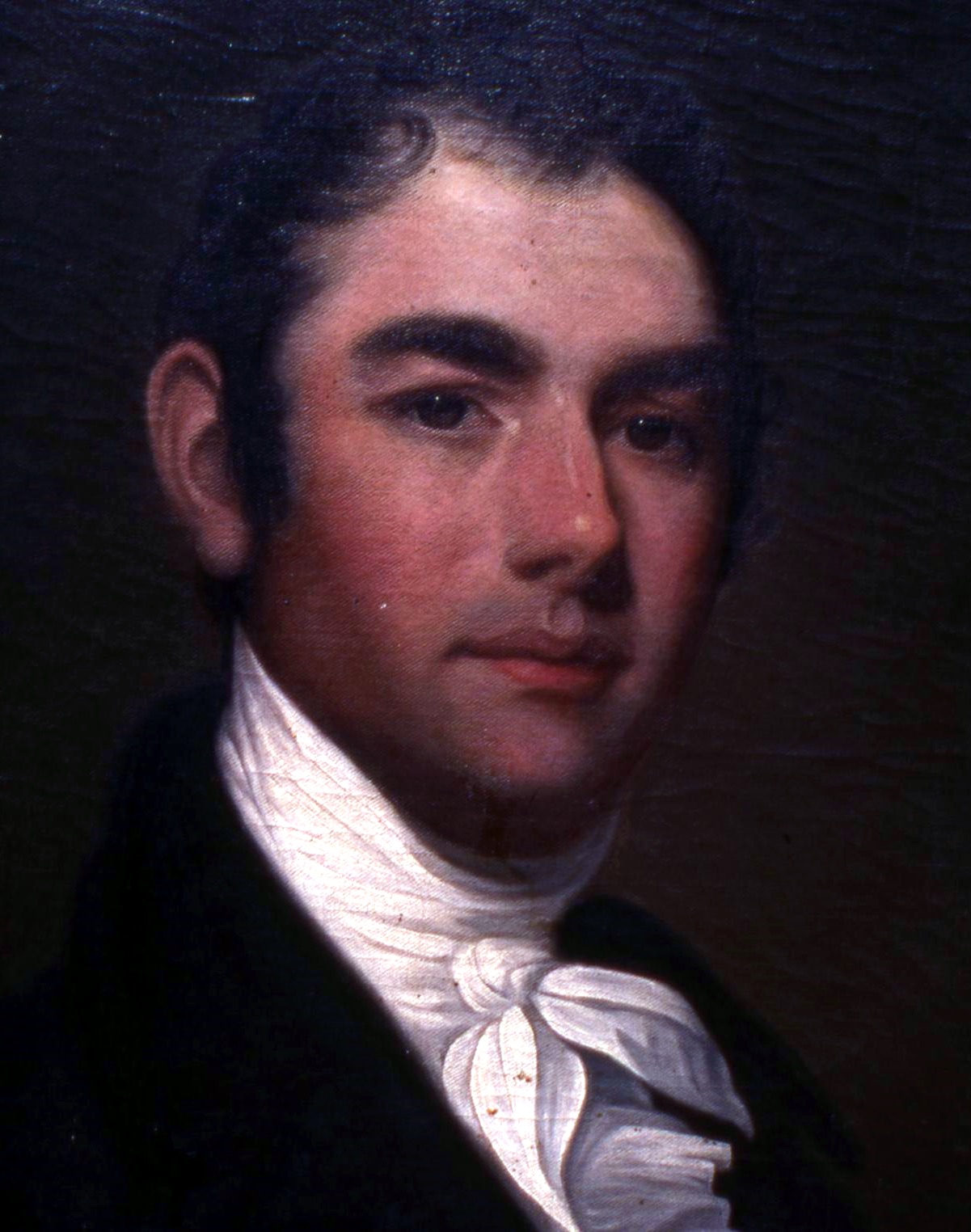

King wasn’t known as the Sultan of Bath for nothing. He had steadily gained prominence in the District of Maine and in Boston. Born and raised in Maine, he worked his way from laborer in a saw mill to owner of one. He went on to building and owning ships, owning a store, investing in substantial real estate holdings, opening the first cotton mill in Maine, and founding the first bank in Bath, a shipbuilding city on Maine’s Midcoast where he settled.

Voters in the coastal communities still overwhelmingly voted against leaving Massachusetts…

He also served in Massachusetts’ House of Representatives and Senate and had connections in high places, namely, his older half-brother, Rufus King, a lawyer in New York who was a delegate to the Continental Congress and the Philadelphia Convention, a signer of the U.S. Constitution, and a U.S. senator (he later also was a presidential nominee).

Late in October 1818, King made the long journey from Maine to Washington, D.C. He met with his brother, Rufus, for advice and support, and with William Crawford, who, as treasury secretary, oversaw the laws regulating the coasting trade. King hoped to sway Crawford into agreeing to a revision of the Coasting Law.

King got lucky. Crawford agreed to support a revision. King returned home and started planning for what he hoped would be the final effort to become a state.

In the early spring of 1819, the revision to the Coasting Law passed in Congress. The new law got rid of the state-by-state stops and fees, and instead designated the Atlantic and Gulf coasts into two districts, with the upshot being that Maine merchants could sail the entire Atlantic coast to Florida without stopping to pay duties.

With the coast (literally) cleared, the floodgates opened. A district-wide vote on separation was scheduled for July 26, 1819. It was the largest turnout ever for a separation vote. While voters in coastal communities still voted more against separation than for it, said Liam Riordan, a history professor at the University of Maine in Orono, there were more yesses than in previous votes—enough to make the difference. The vote for separation passed by a margin of 10,000 votes. At last!

Portland harbor circa 1853. Artist unknown.

Being admitted to the Union as a state should have been—and was expected to be—easy. But to the shock and consternation of all Mainers, the path to statehood became entangled in what has been called the most explosive controversy of its time: an effort to stop the growth of slavery.

In the course of a heart-pounding two months, Maine was embroiled in the political battle that resulted in the Missouri Compromise, which created a boundary for the extension of slavery into new territories, set the stage for the Civil War, and pitted members of the Maine delegation to Congress against each other.

It was not the way Mainers wanted to enter the Union, but in March of 1820, the 35-year struggle to become a state was finally accomplished, with Maine becoming the 23rd state of the fledgling United States of America.