The phrase, “It’s all about relationships,” is an over-worked cliché in describing a job. But for Islesboro’s Lars Nelson, it’s ideal.

Nelson, 66, has worked on the island as a caretaker for a handful of summer folks for 40 years. He’s a private, modest man, and the “relationship” idea emerges only through casual conversation, as he reveals the history he has had with families and with the island’s cottage-style mansions.

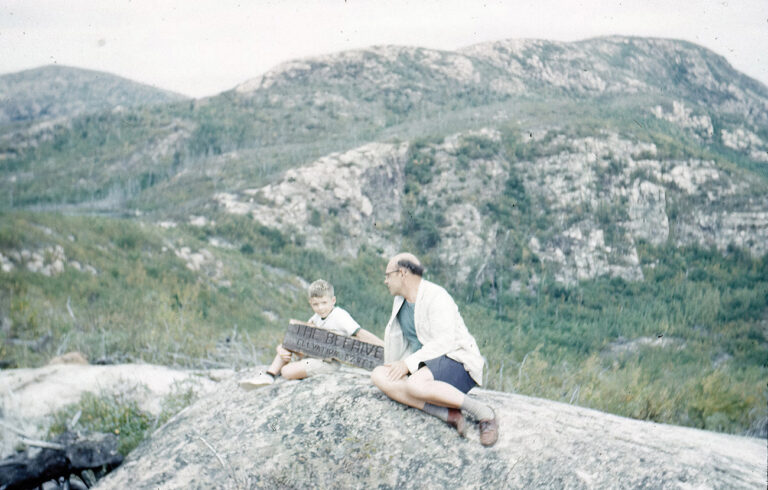

Stopping on a late winter day at one of the houses he cares for—owned by a family whose name would be familiar to most Americans, but which he does not want to disclose—Nelson remembers sailing with the family along the Nova Scotia coast. He was working as a crew member, but it was an experience he remembers as a gift, especially since he was able to bring his son along for the voyage.

This wealthy summer family has even purchased gifts for Nelson’s two children on their birthdays, a gesture that has touched him on a personal level.

As he walks from the driveway to the front of the house, which offers long views over eastern Penobscot Bay, the professional relationship emerges. Nelson looks over the shingled exterior of the home with the fussy eye of a librarian able to spot an out-of-place book. When the contractors who are replacing a glass door see him, they stop work to report their progress. This is part of caretaking, being present, being the owner’s eyes and ears as these century-old houses get the tender, loving care they seem to perpetually need.

With all sorts of digital monitoring devices and services now available that register motion, temperature drops and heightened humidity, it might seem the caretaker is obsolete. Not so.

Nothing can replace a caretaker’s relationship with a house, Nelson explains. He believes he has developed a sense about the place so that he almost knows when something’s gone wrong.

“It’s like how a plumber can hear a drip in the house when no one else can,” he said. Sometimes, he’ll swing by in his pickup truck on a windy, winter afternoon, and—sure enough—find that a door has blown open. And if a monitoring device does notify him about low heat, it is he who must drive over at 2 a.m. in January to try to fix the problem while waiting for a plumber or heating contractor.

It’s rare that a day goes by without a visit to this house.

“We touch base, this house and I,” Nelson says. “We have a relationship.”

If he’s going to be off-island, he arranges for someone else to stop by and look things over. His son, Nakomis, and his wife, Maxine, who does gardening for summer residents, often help.

Summers are especially busy.

“In the summer, it would be 7 a.m. to 8 p.m.,” Nelson says of the length of his days.

Caretakers working for summer island residents tackle a wide range of duties: plowing the driveway in winter, clearing fallen branches after storms, registering and maintaining the island cars, supervising subcontractors, ordering construction and landscaping materials, doing minor repairs, stocking the house with food and other supplies if the family plans a spur-of-the-moment visit, and arranging for visitors to arrive via airplane or ferry.

“When they need you, you show up,” he says. “You’ve got to be able to listen, to hear what people want.” The summer folk are savvy about the service they expect, so being accountable, reliable and honest are key.

“I enjoy it. The places I work, I’ve been there so long. I do a little bit of everything, except carpentry and plumbing.”

Though wary of disclosing too much, Nelson acknowledges that he is paid a salary, much like a retainer, for his work. These days, more summer folk are paying caretakers by the hour, he notes.

And island caretakers help each other.

“You rely so heavily on your relationships,” he says. “That camaraderie is genuine.”

Like many who have chosen island life, the story of Nelson’s landing on Islesboro is wrapped up with his values and identity.

He was born in Sweden, but was adopted at birth by a family of Swedish descent in Salt Lake City, Utah. His grandparents had a house on the north end of the Islesboro, and he was drawn to it.

After some study at Maine Maritime Academy, Thomas College and the University of Southern Maine, he came to Islesboro and built a log cabin on the family’s land with Ben Moody, an older Islesboro native.

In 1971, Moody offered him work if he had a chainsaw and a boat.

“I didn’t have either,” he recalls, but was able to borrow them from his parents, and worked cutting trails on privately owned Job Island. That led to other island summer jobs.

Moody, long dead, remains a mentor figure to Nelson, as he explains that much of what the older man imparted didn’t take hold until years later.

“There are so many things he whispered into my ear,” Nelson said, which he finds guide him in his work today. It was Moody who in the mid-1970s turned over the caretaker job of the house we visit to Nelson.

“For me, this island is just enchanting. It’s a heaven for me. I feel so privileged. I love doing what I do. It’s just so satisfying to do something with your hands.”