MBNA. Four letters that actually stood for nothing, yet oh-so-much, in the mid-1990s through 2005.

The Delaware-based credit-card lender, spun off from Maryland Bank, National Association—hence the name—dominated the Midcoast landscape for those years. From 50 jobs in Camden in 1993 to 4,500 statewide by the early 2000s, its growth here was dramatic and visible.

Some companies quietly go about their business and hope to avoid controversy and dodge media attention. They write checks to national charitable groups and stay out of local initiatives.

Not MBNA.

The company and its CEO, Charlie Cawley, were big fish in the small pond that is Maine. They introduced corporate culture to towns that had never before seen it, and sometimes, it was an uneasy marriage. In Knox and Waldo counties, MBNA’s presence was at its largest and most dramatic. The phrase “800-pound gorilla” was used more than once by media pundits.

But despite what critics said—and they said a lot—as Maine staggered out of one of the worst recessions in decades in the early 1990s, the jobs that MBNA offered were a shot of adrenaline to the Midcoast’s anemic economy. And the corporate and personal giving—particularly on the part of Cawley—gave new meaning to the word generosity.

In July, ten years will have passed since Bank of America purchased MBNA and those four letters passed into history. But the company’s impact remains. Many of the large office complexes built around the state, sold by Bank of America at bargain prices, are occupied by other businesses today.

Beyond the jobs and the infrastructure, MBNA may have had an even more profound hand in polishing—if not remaking—the public landscape of the Midcoast and some of Maine’s islands. Education and schools, libraries, YMCAs, art museums, performance spaces, parks, and several nonprofits—including the Island Institute, publisher of Island Journal—were lifted up and set on new, firm foundations. It was a level of giving that recalled 19th-century donors like Carnegie and Rockefeller.

Some of what MBNA did never got reported. One small anecdote: The company paid for teachers at elementary schools to quietly buy the ubiquitous L.L. Bean backpacks for poorer kids who didn’t have them. One secret gift, spilled to the press years later by former governor Angus King, was sending Christmas gifts and food to poorer families in Knox and Waldo counties.

In the public arena, perhaps the most stunning beneficence came when the K–8 Lincolnville Central School had to close suddenly due to mold problems. The state would build a new school on the site, but where would classes be held until then?

MBNA stepped in and built a school—in 54 days—on the grounds of its retreat center on Ducktrap Mountain, a building that most area towns would trade their schools for in a heartbeat.

Any attempt at quantifying the economic impact or listing the donations is doomed to fail. But ten years later, it’s a story that needs to be told.

I was a reporter and editor in Belfast, Rockport, and Rockland during those years, and as I think back, it seems like a dream—a vision of a train roaring through, stopping long enough for gifts to tumble out. On a July morning in 2005, it was over.For we journalists in the Midcoast, MBNA also was a gift that kept on giving. Each announcement—a new profits peak, more jobs, new buildings, six-figure donations—left us shaking our heads in wonder. And it was good news, not the dreary reporting of a plant closing. The towns in which we lived and were raising our children were made better, with new or improved schools, parks, libraries, and on and on.

~

There were critics, of course; there was a dark side, and drama and conflict followed as a large national corporation tried to settle into small New England villages.

Critics claimed MBNA bullied the local newspapers. They said the nature of the business—lending through credit cards—hurt people, and society as a whole. The jobs paid well and the offices were far from the shoe and fish factories of the past, but many observed that the high-pressure phone sales were more like piecework than not.

Cawley was generous, but he wore his heart on his sleeve, and when his gifts and expansions were questioned or opposed, he was hurt, and that hurt sometimes led to anger. Plans to grow in Camden were rebuffed by many, and it seemed that Cawley responded by angrily shunning Camden for Belfast, where the company’s presence would grow to 2,500 jobs.

Later, Cawley would say he understood the trepidation about the rapid growth in Camden; more community input was sought for an expansion in Rockland. With less fuss, call centers were opened in college towns like Brunswick, Farmington, Fort Kent, Presque Isle, and Orono.

The conspicuousness of the company’s spending—like buying a small house, fixing it up, and then tearing it down—rankled many a Yankee’s frugal values, and the yachts, private jets, and large black SUVs enjoyed by top management also seemed to be consciously flaunted.

The dramatic arc that became a pattern for MBNA was established early on. Flipping through the pages of the Camden Herald at the Walsh History Center at the Camden Public Library—the first established through MBNA largesse, the second, greatly expanded by it—the beginnings of the story unfold.

The January 23, 1993, issue reports that MBNA officials toured several possible office locations. The company would create 70 to 100 jobs, “a good fit for the town,” a local architect told the paper.

On February 11, the news was that new offices would open on June 1, with 50 to 60 jobs, growing to 150. A company vice president noted that Camden was not unknown to senior managers. “MBNA has been holding management meetings here for over ten years,” Richard Struthers said.

The March 4, 1993, Herald announced that MBNA would match funds of up to $250,000 for a local group restoring the Camden Opera House. This, just over a month after announcing its expansion in Maine, and before a single paycheck had been issued. The initial restoration budget had been $125,000; now, much more was possible, and indeed, the opera house was remade into the stunning venue it is today.

The story notes that MBNA “has expressed the hope that their contribution will confer a lasting benefit on the Midcoast area.”

The company planned to lease part of a former mill, but in the April 29 paper, the headline told the tale: “A New Era—MBNA Purchases the Knox Mill,” all 106,000 square feet of it.

The management retreats in Camden were not coincidental. Cawley’s grandfather had lived in Lincolnville, and run clothing businesses in Belfast and Camden.

Those Camden roots are part of an oft-told story. As a young man, Cawley was returning to college and needed new tires on his car, but was unable to afford them. Camden’s Bob Oxton, who apparently operated an auto shop, gave Cawley the tires, allowing the payment to follow.

Now, Cawley could repay Oxton more substantively, hiring him to help with the new building. Some saw a conflict of interest in Oxton, the town’s fire chief, moonlighting for a private company that owned the biggest building in town. An editorial in the May 6 paper defended Oxton and the hiring, and the fuss was over.

In fewer than four months, the pattern was set: an expansion, jobs, more jobs than originally planned, a building purchase beyond what was planned, a high-profile donation, controversy, resolution. It would continue to play out elsewhere.In retrospect, the company—which already had offices around the United States when it came to Maine—rode the tide of a booming economy through the late 1990s. Profits cracked the $1 billion mark in 1999; a year later it was $1.3 billion, then $1.7 billion in 2001, and $2.3 billion in 2003. Expansions in the UK, Ireland, and Spain followed.

Company officials regularly reported that its Maine offices performed better than others around the country. Cawley built a waterfront summer home in Camden. (In 1999, he hosted a fund-raiser for then-candidate George W. Bush at the house; former president George H. W. Bush was a guest at several MBNA events in Maine; and Cawley and his top executives were among the biggest donors to Republican campaigns.)

Describing itself as a bank without a lobby, MBNA was a cast-off division of Maryland Bank that Cawley and others took over and built around what they called affinity marketing. Credit cards with organization logos were issued to college alumni groups, professional associations, and other such groups. A portion of the purchases went to the groups, thereby ensuring they would promote their use.

Cawley has been quoted as saying his goal was to give away his wealth, and he certainly gave a lot of it away. As CEO, he imbued the company with that same ethic. MBNA’s generosity would be seen across a host of arenas. After the Camden Opera House, the company in 1994 donated $1 million to Penobscot Bay Healthcare, but education and the arts were major themes. Some of the bigger-ticket donations helped to renovate and expand the Rockland Public Library, the Camden Public Library (Barbara Bush appeared at the ribbon-cutting ceremony), and the Belfast Free Library.

The MBNA Foundation, Cawley, or both also paid to expand the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, building the Jamien Morehouse Wing, named for Island Institute founder Philip Conkling’s late wife, and turned an old church into the museum’s Wyeth Center. They helped pay for Belfast’s first YMCA building, and to expand Camden’s into a regional facility.

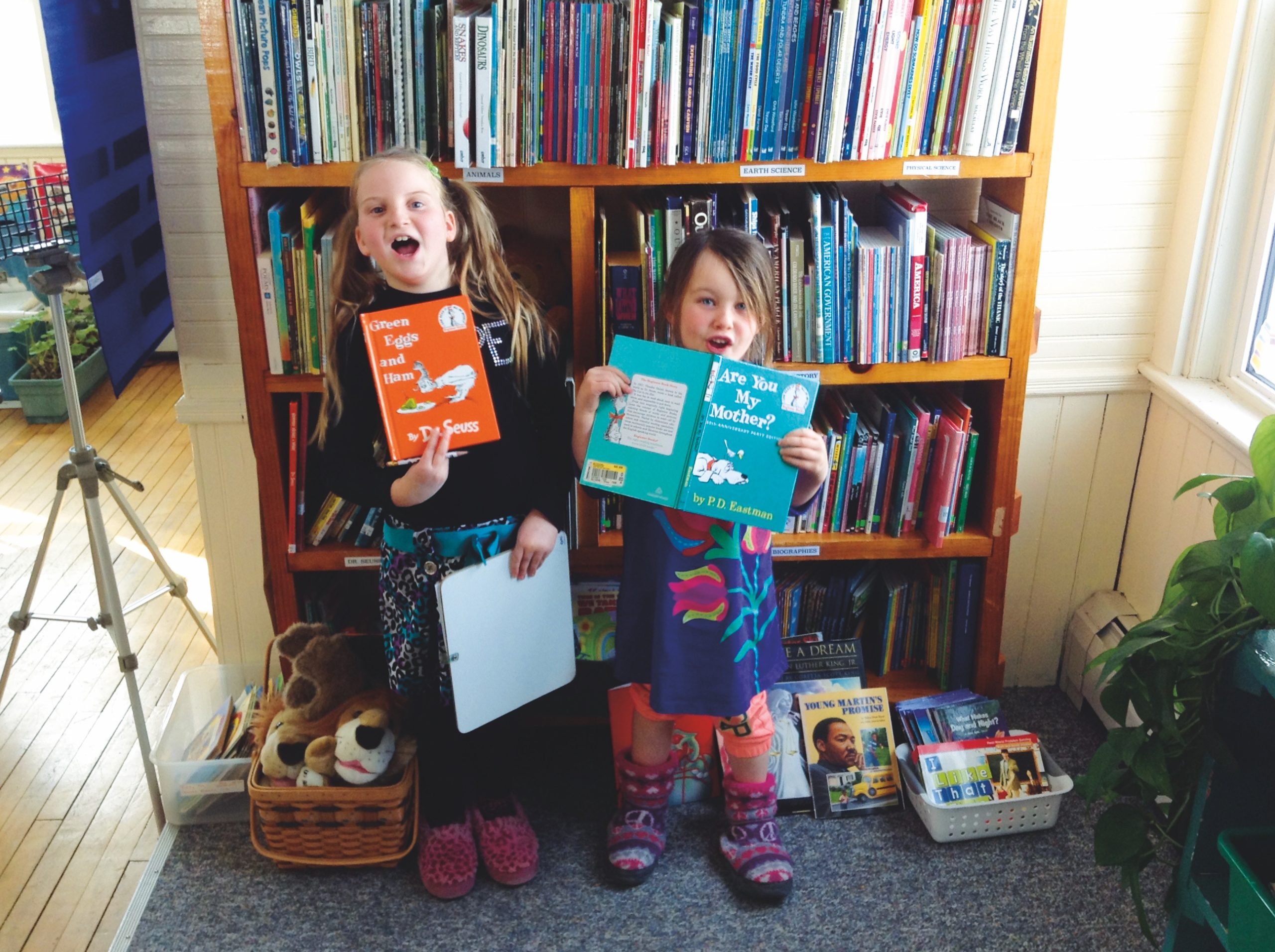

On the islands, the company donated to North Haven’s effort to create Waterman’s Community Center, and was a major source of funding for the renovated and expanded Vinalhaven school. It helped to fund the purchase of seven miles of shoreline on Frenchboro, as well as improvements to the school, library, historical society, church, and parsonage. It gave grants to 13 island libraries.

“Charlie Cawley was on every nonprofit’s radar in Maine, and particularly in the Midcoast,” Conkling remembers. “Everybody wanted to talk to Charlie.”

In the fall of 1999, Conkling and Institute cofounder Peter Ralston booked a meeting with him and explained the needs on year-round islands. Cawley wanted to see the islands, and proposed visits to Frenchboro and Swan’s Island.

“Little did we know this was going to be a tour in a helicopter,” Conkling remembered, chuckling. On Frenchboro, “We take Charlie up to see the one-room schoolhouse,” and from the small bookshelf that passed for the school library at the time, Cawley “pulled out a science reference book, published in 1964, that mentioned man going to the moon someday.”

Cawley made an immediate decision, saying, “ ‘I’m going to start an island library program,’ ” Conkling remembered.

The donations dramatically impacted not only island libraries, but also school and cultural enrichment programs, he said. On Vinalhaven, the state paid for a new school, but would fund only a shared library for the K–12 students. To build a better library, MBNA agreed to match up to the $1 million raised locally, and did.

“Nobody in Midcoast Maine had seen that kind of grantsmanship,” Conkling said.

The company also funded the start of the Island Fellows program.

And then came a gift for the Institute. Conkling remembers a late-night call from Cawley, who said a sales agreement on the former Senter-Crane department store in Rockland would expire the next day. Did Conkling want it?

Despite the myriad concerns that raced through his brain, Conkling said a voice inside told him “Just say yes,” and he did. The new building, sold to the Institute for $1, “truly put us on the map,” allowing the growing staff room to work, and providing space for Archipelago, the store and fine arts gallery, on Main Street.

One of the most profound impacts MBNA had was through the hundreds of college scholarships it awarded to students in Knox and Waldo counties. Later, the company included students in nine island communities in Hancock and Cumberland counties. Now, long after the corporate jets have left, those young men and women carry their education throughout their lives.Before joining the Belfast Republican Journal newspaper, I worked for a social service agency in town, doing job training. A chicken-processing plant, sardine cannery, shoe factory, and french-fry processor were among the big employers. Some of those who came to our office for help were women who had developed carpal tunnel syndrome from cutting sardines with scissors, day in, day out, or who suffered bouts of “chicken poisoning,” some kind of bacteria that took hold in the cracks in their hands.

Flash forward to 1995, when MBNA executive Shane Flynn was giving me a tour of the beautiful new Belfast office. I heard several women’s voices calling out, “Hi, Tom!” I recognized them as the same former factory workers. Instead of cold, wet, noisy conditions, they now worked in a climate-controlled office, sitting comfortably in their cubicles.

Another personal note: As someone who loves his adopted hometown of Belfast, I am regularly reminded of MBNA each time I walk or drive along the waterfront. When the sprawling concrete chicken plant that dominated much of the waterfront went belly-up in 1988, it sat vacant—covered in graffiti, decrepit and smelly—for almost ten years. City government talked about getting rid of it, but nothing was done.

MBNA purchased the property with the idea of building offices there, where its yachts could dock, but instead, Cawley decided to build a park for the city.

Years later, Front Street Shipyard revived the other end of the waterfront, but I believe if that park had not been built, a business like the shipyard would have looked elsewhere.

In July 2005, while reporting for the Bangor Daily News, I learned that Bank of America would be buying MBNA. On a conference call that included questions from the Wall Street Journal, LA Times, and CNBC, I was surprised to hear my name called. I asked Cawley’s successor at MBNA what he would say to those workers arriving at the Belfast office that morning when they learned of the sale. He said that if nothing had been done, there would be no more MBNA. The company, other sources said, had resisted diversifying into home mortgages and insurance, and risked running out of new markets for its credit-card lending.

Today, there is no more MBNA. But the legacy remains.

Angus King, now a US senator, was Maine’s governor during those years. When the company was bought, he summed up what it meant: “If I had sat down in 1994 with a blank sheet of paper and written down the ideal company for Maine,” he said, “it would have been MBNA.”

Tom Groening is editor of Island Journal and The Working Waterfront.