Of all the Maine islands I favor Monhegan, a solitary whale couchant in a blue field of sea, sixteen miles distant with nothing beyond but more sea and the coast of France.

—Martin Dibner, Seacoast Maine: People and Places (1987)

It has been 400 years since the English explorer Captain John Smith anchored off Monhegan and took stock of the island. While Smith was not the first to visit, his stopover remains the founding event upon which Monhegan hangs its history. Indeed, that occasion, plus many other sail-bys and anchorings by adventurers “from away,” led Ida Sedgwick Proper (1873–1957), the painter, suffragette, and islander, to title her 1930 book Monhegan, The Cradle of New England.

Proper offered plenty of proof for how the island served as the rocky bassinet for the infant region. She began, most properly, by hailing its long line of fishermen, dedicating her history to those toilers of the deep “of all times and of all countries, whose courage and faith made discovery of the North American continent possible.” As if to bolster her argument for this tribute, Proper noted that all of Christ’s apostles were fishers of the sea, “and ever since fishermen have been found trustworthy, ingenious and courageous.”

Monhegan has suffered somewhat from its isolated setting, even as the islanders have trumpeted its independence. True, the island is remote by Maine island standards—it sits ten miles from the nearest mainland—but it hasn’t been 400 years of solitude.

In recapping the numerous voyages to the New World that included visits to and/or sightings of the island (by what historian James Phinney Baxter referred to as the “avant couriers of colonization”), Proper included some of the earliest descriptions of Monhegan. A favorite, from the pen of Englishman David Ingram, echoes the “solitary whale” image of novelist Martin Dibner’s epigraph above. Looking seaward one morning from “Pemcuit” (Pemaquid) in 1569, Ingram saw “a great island that was backed like a whale. I first took it for a whale, as those fish in that country are easily taken for islands at a distance, so high do their backs rear out of the sea, and so enormous are they that one would load a hundred ships.”

Returning to Captain Smith: Proper called him the “Publicity Agent of New England.” In his Maine: A Narrative History (1990), historian Neil Rolde pushed that notion further, noting how Smith’s glowing reports “would make a Chamber of Commerce booster proud.”

While the Englishman’s principal objectives for the visit—“to take Whales and make tryalls of a Myne of Gold and Copper”—failed, Rolde points out that he still promoted the region, including Monhegan’s fertile soil: “Yet I made a Garden upon the top of a Rockie Ile in 43½, 4 leagues from the Main, in May, that grew so well, as it served us with sallets in June and July.”

Proper is one of a number of historians who has a personal connection with—and, therefore, bias toward—Monhegan, which adds a special dimension to their chronicles . . . a boastful attitude, shall we say, that for aficionados of the island is gratifying. When she states without reserve that “Monhegan is the most famous deep sea island on the Atlantic seaboard,” we nod and read on. (She even hailed Monhegan’s accession by Massachusetts in December 28, 1822. Monhegan was, she reported proudly, as if it were the NBA draft, “the first island selected by Massachusetts for her portion.”)

Historian Charles Francis Jenney took the title of his study, The Fortunate Island of Monhegan (1922; second edition, 1927), from the gentleman historian James Rosier’s oft-quoted description from May 17, 1605: “It appeared a meane high land, as we after found it, being but an Iland of some six miles in compasse, but I hope the most fortunate ever yet discovered.” Like a movie promoter pulling out the best piece of a review to highlight in an ad, Jenney focused on “fortunate” despite the qualifying nature (“I hope”) of Rosier’s statement. The author did go on to explain that the purpose of his account of the island was to “describe the fulfillment of his prophecy,” which he did.

To address the question of the origin of the island’s name, Jenney asked fellow Worcester resident Lincoln N. Kinnicutt to examine the derivation and meaning of Monhegan. Kinnicutt concluded that “the Island” was the best interpretation, adding, “and there is a strong probability that to all the Indians on the Maine coast it was the island where the white men came year after year ‘in their big canoes with the white wings.’ ”

Historian Charles McLane agreed, taking his cue from Fanny Hardy Eckstorm’s Indian Place-Names of the Penobscot Valley and the Maine Coast (1941): “the island or Great Island.” He also offered some of the other names given it by early visitors: “Verrazano called it Anne after a teenage princess of Navarre; Champlain called it La Nef because it looked like one from a distance; Rosier, or Waymouth, called it St. George’s Island . . . ;and Captain John Smith . . . humored James I by naming it Barties Isles . . . presumably after one of James’ retainers.”

Reading Penney’s narrative of the island’s history, one is struck by harbingers of the future. One glowing report of the fishing off the island from the early 1600s brings to mind issues of overfishing today: “n five or six hours’ absence we had pestered our ship so with cod-fish, that we threw numbers of them over-board againe.” Captain Smith reported landing more than 60,000 cod “in lesse than a month.” The market was global: Tons of fish were being carried back to England, Spain, and France.

According to Jenney, the “day of the explorer” came to an end in the mid-1600s. By that time, he wrote, “a voyage to the Maine coast was no more momentous than one of like character would be to-day, and such voyages were not heralded or recorded.” Monhegan retained its importance as a fishing station, and was even visited by pirates.

Toward the end of the 17th century, a settlement began to form. Jenney noted the appointment of the first constable, John Dillon, in 1673. A year later, the first innkeeper, the same Mr. Dillon, but now spelled Dolling (and later Dollen), was authorized “to keepe houses of publique intertaynments” and to “retayle beere, wyne, and liquors in ye severall places for the yeare Ensuing according to law.”

The island became a refuge during “the Indian troubles.” After the fort at Pemaquid was captured and destroyed in 1689, the “entire region” was “substantially abandoned,” according to Jenney, who dated the end of Monhegan’s “golden age” to this event. McLane, by contrast, offered evidence—deeds and such—to show that the island “was not vacated because of King Philip’s War.” He also noted that over time, Pemaquid no longer served as Monhegan’s “polestar”; the island came to rely on Boothbay, Thomaston, and Port Clyde.

The island changed hands many times over the years, but a new chapter in its history began in 1777 when the deed to Monhegan was conveyed to Henry Trefethren, a cabinetmaker from Kittery. He and his descendants, along with members of the Starling and Horn families, helped build a year-round settlement on the island. As McLane put it, with the sale to Trefethren, “the modern history of Monhegan may be said to begin.”

LOBSTER BOTTOM

By 1832, there were between 75 and 100 people on the island living in a dozen or so houses. A lighthouse, illuminated by sperm whale oil, had been built in 1824. In 1854, a fog station with a 2,500-pound bell was erected on the adjacent island of Manana. A municipal library was established as early as 1845, the post office in 1858. The Monhegan chapel came along in 1880; a public wharf was constructed in 1908.

By the turn of the century lobstering had replaced most other forms of fishing. Concerned with the protection of the fishery, islanders successfully petitioned the Maine Legislature in 1907 to establish a closed season. Since then, trapping lobsters has taken place in the off-season (“Trap Day” is now October 1, where it once was January 1).

In his acclaimed The Lobster Coast: Rebels, Rusticators, and the Struggle for a Forgotten Frontier (2004), Colin Woodard covers a recent fight by islanders to maintain rights to its precious “lobster bottom,” the territory it has long fished and conserved. When fishermen from the mainland began setting traps near Monhegan, Woodard recounts, the islanders dispatched a crew to Augusta to lobby then-governor Angus King.

Their campaign to keep non-islanders away owed its success to some unusual tactics, such as eight-year-old Kyle Murdock “engaging senators in the elevators and paging for members of the house.” That same Kyle Murdock stars in Jamie Wyeth’s painting Dead Cat Museum. And he is the Kyle Murdock who went on to found Sea Hag Seafood, a lobster-processing company in St. George. In October 2013, he was awarded a $40,000 grant and honored with a young entrepreneur award from the Hitachi Corporation.

McLane is especially helpful in filling in the 19th-century demographic history of the island, including the “restlessness” of the island’s population: The average length of a family’s residence after 1850 was ten years. The mobility of fishermen may have had some bearing on off-island moves. “When artists and rusticators invaded the island,” he wrote, “there may have been even more incentive for native residents to move on.”

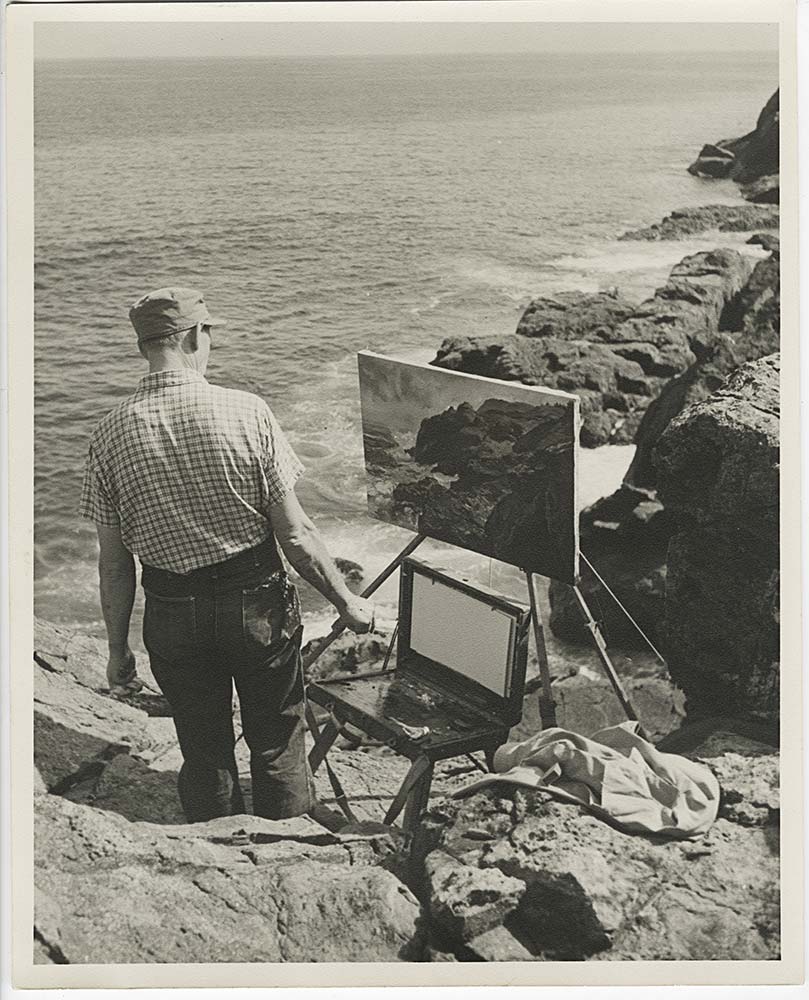

Where McLane saw the growing influx of seasonal visitors as something of a scourge, Jenney ended his narrative of Monhegan with an acknowledgment of, and tribute to, the artists who frequented the island. The island’s “beautiful woodlands, waving moors, picturesque buildings, grand headlands, restless, mighty, and eternal sea,” as interpreted “by the genius of the artist,” he stated, “delight thousands the country over.” Thanks to these images of the island, Jenney could declare that “the hope of the ancient chronicler” had been realized: “In verity it has been and is a fortunate island.”

“THE ARTISTS’ ISLAND”

One supposes there were island natives who took umbrage at the title of Will and Jane Curtis’s and Frank Lieberman’s landmark book, Monhegan: The Artists’ Island (1995), as if those easel-bearing men and women owned the island. This landmark publication simply offered a broad accounting of the rich and remarkable array of art that has been inspired by the island.

That legacy continues to expand every year. Artists from across the country and around the world continue to find their way to the island. The Monhegan Artists’ Residency, which has introduced nearly 50 Maine artists to the island, and is celebrating its 25th anniversary this year, added a new residency for Maine schoolteachers last year. And where the roster of island artists used to be predominantly male, nowadays it is much more balanced, with such groups as the Women Artists of Monhegan Island gaining visibility.

One way to consider Monhegan’s larger reputation over the last half-century or so is to compare the two feature articles on the island that have appeared in National Geographic magazine, in February 1959 and July 2001. The focus of the earlier piece, as its title proclaims, was lobstering: maine’s lobster island, monhegan. In his short text, William P. E. Graves, a staff writer at the magazine, noted that “Monhegan makes its living trapping the armor-plated delicacies of the deep.”

The featured photographs, all black-and-white (in an otherwise all-color edition), were taken by the Finnish-American photojournalist Kosti Ruohomaa (1913–1961), one of the great documenters of Maine. They represent a decidedly off-season island, from “hardy fishermen” playing cards in a smoke-filled fish shack to a “solitary villager” making his way down the snow-blown main road.

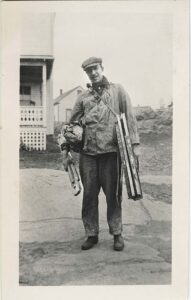

The “summer artists and vacationers” earn but a passing mention. Yet among Ruohomaa’s photos is one of the Estonian-born painter Andrew Winter (1892–1958), who lived year-round on the island from 1940 till his death. Pipe clenched in his teeth, goggles atop his head, he is shown helping a neighbor carry lobster traps down to the dock. Winter took on island roles beyond that of artist, and thereby became a beloved member of the community.

By contrast, the 2001 Geographic feature by Cathy Newman opens with a candid by photographer Amy Toensing, of painter Frances Kornbluth standing in front of the laura b, the island’s ferryboat, docked at the island. The title—welcome to monhegan island, maine. now please, go away—goes with the look on Kornbluth’s face: a kind of wariness, and maybe a bit of displeasure. Her visage probably isn’t as daunting, or as humorous, as actor/painter Zero Mostel’s must have been when he allegedly stood on the Monhegan dock and yelled out to a boatload of tourists about to land: “Plague! Plague! Cholera! Go back!”

The two Geographic pieces share a common visual element: a photograph of the Odom brothers, Doug and Harry, longtime mainstays of the year-round community who ran the island store. Ruohomaa pictures them in oil hats and slickers on a winter run to haul traps. (Later in life, they sold land to young fishing families “for a fraction of what the market could have borne,” writes Woodard.) Toensing’s portrait, titled Inseparable Brothers, is intimate in a different way: The brothers lie in twin beds in their simple island bedroom, their dog Taxi in a basket between them.

The history of Monhegan is a history of its people. It is master carpenter Will Stanley, who built many of the houses on the island; Theodore Edison, son of the inventor, who set in motion the preservation of the island; Ray Philips, the shepherd and longtime hermit of Manana, Monhegan’s “nursling” island that forms its harbor; painter Jacqueline Hudson, who spearheaded the creation of the Monhegan Museum; Ted Hoskins, minister of the Maine Sea Coast Mission, offering solace and hot chocolate aboard “God’s tugboat,” the Sunbeam. It is the shopkeepers and librarians, summer hotel staff and boat captains, the birders in autumn, and, of course, those “trustworthy, ingenious and courageous” fishermen.

The island is not everyone’s cup of tea. During his Monhegan visit, Woodard encountered a tourist who expressed bewilderment at the lack of stores. “Well, why do people come here, then?” she asked.

The answer, of course, lay all around her. We stood in the center of one of the great anomalies of early-21st-century American life: an ancient, self-governing village, essentially classless and car-less, whose homes, sheds, and footpaths appear to have thrust themselves out of the wild and arrestingly beautiful landscape.

* * *

The history of Monhegan continues to unfold—that is the nature of time—and the island will face challenges and quandaries as it goes forth into the 21st century. In an opinion piece in the Bangor Daily News on November 8, 2013, inspired by the siting of two windmills near Monhegan, Suzanne MacDonald, Community Energy Director at the Island Institute, offered these thoughts:

Monhegan is an iconic part of Maine that is on the brink of survival. There is probably no single square mile more important to American art. But Monhegan is also known for leading the state in lobster conservation efforts, in affordable housing programs, for networking remote schools with cutting-edge technology, and for land conservation initiatives. Despite these strengths, the high cost of living is challenging the sustainability of the island’s year-round community. A neighboring project benefiting from massive amounts of federal and state support should seek to contribute to local efforts to overcome these challenges.

In a talk this past winter at the Skidompha Public Library in Damariscotta, Reverend Bobby Ives, who served as pastor on Monhegan for several years in the 1970s, recalled part of a weather report from Maine Public Radio’s renowned meteorologist, Lou McNally. “It’s a windy day across the state of Maine,” said Lou, adding, “All you people on Monhegan Island, hold on!”

Hold on, indeed; this “fortunate” island has a lot of history ahead of it.

For more information on Monhegan’s quadricentennial celebration, visit the town’s 400th anniversary website.