Fogo Island’s story is one of survival. In modern times, this 92-square-mile island has survived the provincial government’s attempts to resettle the population, the demise of the cod fishery that sustained Newfoundland for centuries, and the severe economic downturn caused by loss of the cod.

But the rugged residents of Newfoundland’s largest island were hanging on for dear life long before Joey Smallwood tried to move them off-island in the 1960s, or the cod fishery closed in 1992. Prior to these crises, the St. John’s salt fish traders had a company-store choke hold on all rural Newfoundland’s fishermen that kept them barely subsisting for more than a century.

The residents of Fogo Island have traditionally done everything they could to keep their island existence viable, against heavy odds. These people, who possess an ingenuity fertilized by the rigors of a subsistence culture and the constraints of island living, have survived, and now may have a chance at thriving, due to the creative efforts of a wealthy native who returned home to live and help her island.

“The first big changes came in 1960 when the government wanted us to resettle and we decided we weren’t leaving. The men formed the co-op—it’s the lifeline of Fogo Island,” said retired teacher Christine Dwyer of Joe Batt’s Arm. “In 1972, we decided that to have better education, we’d amalgamate all the schools. That was the beginning of Fogo Island.”

For its size, Fogo’s unique features are many. It’s home to 11 separate communities with a total island population of just under 2,400. Nine of the communities had schools. Fogo was the first to end the province’s custom of religious schools—one for each denomination no matter how small the town—and create one, central, nondenominational school.

It has a fisheries co-op so innovative that it is used as a model in Ottawa for other communities. It has a native caribou herd. It was the site of the first ground-warning radar station in the North Atlantic during World War II. It has a thriving fishery that replaced the vanished cod, and three fish plants—one each for crab, shrimp, and assorted groundfish, mostly turbot. To save money, the communities amalgamated into one municipal government for the entire island.

Not unique to Fogo were the same troubles that still plague nearly all of rural Newfoundland: a lack of jobs, an outmigration of young people seeking jobs, and, therefore, a dwindling and aging population. But Fogo Island, once again, is defying the odds. Some young people are returning, there’s an uptick in employment, and increased tourism offers the prospect of related small businesses.

THE COBB EFFECT

The increase in tourism may be credited to Zita Cobb. Credit for the returning young people can be divided between Cobb and the proliferating offshore oil industry.

Cobb grew up on Fogo Island, one of seven children of a fishing father. Their dad gave up fishing and moved to the mainland in the 1970s, when small-boat fishermen were forced to invest in larger long-liners to chase the dwindling cod further offshore.

Cobb attended Carleton College in Ottawa and embarked on a round-the-world odyssey of oil company jobs and treks through Africa, ending when she stepped down at age 43 from her job as CFO of a California-based fiber optics company. She cashed in her stock options for millions, sailed her 47-foot yacht around the world for four years, and then returned home to Fogo in 2005.

Cobb began investing in Fogo Island immediately upon her return by giving college scholarships to graduating students, until an island woman pointed out that Cobb was “paying our children to leave.”

“I realized we needed to do something that would make a meaningful long-term difference to folks on the island,” Cobb said. She formed the nonprofit Shorefast Foundation with four goals: Fogo Island arts—residencies that cover artist expenses; “straight-up preservation,” such as restoring old houses and keeping alive the tradition of building punts; business assistance in the form of micro-lending; and the Fogo Island Inn.

Four art studios are now open, with two more planned. Each is near a different community, and is a small, simple, but cleanly beautiful modern structure that doesn’t resemble the island’s typical buildings, but fits in and echoes its stark beauty.

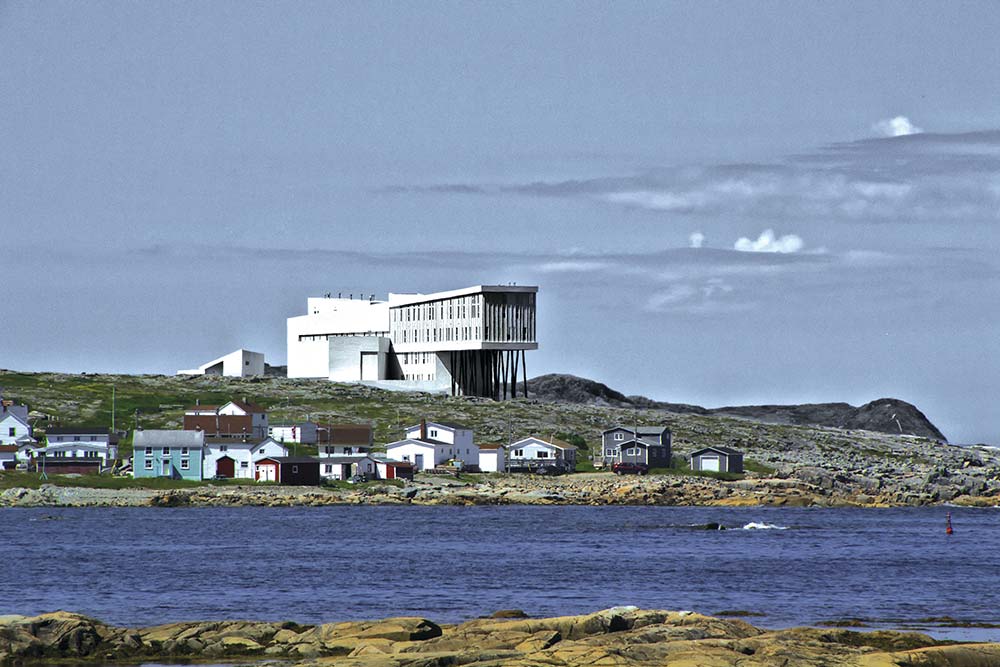

The artists’ studios and the four-story inn, which opened in June 2013, were all designed by a young, Newfoundland-born architect, Todd Saunders, whose Saunders Architecture is based in Norway. The inn is a for-profit business, but it’s owned by Shorefast.

Offering only 29 rooms also makes the inn unusual. Cobb sees it as “big enough, but small enough,” and admits it’s not the typical size for a destination inn.

“Most of the cost is the main infrastructure—heat, kitchen, etc.—so conventional wisdom says you may as well hang as many rooms onto it to get your money back.

“But the inn is a gift to the community, it belongs to the charity; there’s no payback—no five-year payback, no hundred-year payback. That changes everything,” said Cobb. “We are operating a business, so we have to make a profit, but nothing like the investment on capital.”

It’s also a matter of scale: “The more they pay, the fewer people have to come.” When the inn first opened, it won awards for food, design, and hospitality.

Cobb attends high-end tourist shows to sell the inn’s pricey rooms to vacationers. At a recent show in Marrakesh (“You’ve GOT to be there”), she was standing next to representatives of luxurious, extravagant Oman resorts.

“What we have to offer is more ‘embodied,’ ” said Cobb. “Our inn came from the ground and history up. We’re coming at luxury in a different way,” is the pitch.

“Everything is made from natural materials. There are no laminates, just solid wood,” she explained. All the inn’s furniture and light fixtures were built by island craftsmen. The native black spruce, often used for building punts, provides the exterior siding. The rooms are ample, spare and modern, but the furnishings add hominess and tradition.

Island women hooked rugs and sewed more than 200 quilts with traditional island patterns in different weights for different seasons, and each bears the name of the woman who sewed it. As much as possible, materials come from Fogo Island, or at least Newfoundland. Organic cotton wraps the foam mattresses made in Ottawa from rubber harvested sustainably in Indonesia.

“It’s all about new ways with old things,” said Cobb. “When we came up against building codes, we had to figure out the plague of sameness. Every building material is the same size, but people don’t think about human joy. You get joy from specifics.”

Many rooms in the steel-framed, highly insulated inn contain wood-burning stoves to give guests “a warm hearth to gather around,” while solar panels provide hot water for the radiant floor heat and the laundry. Rainwater collectors gather water to flush toilets and provide a heat sink.

FILM ON DEMAND

Jack Stanley first came to visit Fogo Island eight years ago. He bought a book about one of the island villages, Tilting, by Robert Mellin, and brought it back to Montreal with him.

“I dreamed about getting back to Newfoundland. The book was one of the main reasons,” said Stanley. Now he lives in the town of Tilting and works as director of the program for Fogo Island Arts, developing the culture and arts program that includes artist talks at the inn.

“The international residency program is the primary focus,” said Stanley. “Guests at the inn like to visit the artists at the studios.”

In the 1960s, the National Film Board (NFB) of Canada sent people to Fogo as part of a “Challenge for Change,” using film to engage communities that were struggling. The resulting films are now “playing a big part in bringing international tourism here,” said Stanley.

“The NFB is in the process of digitizing every film they’ve produced, and Shorefast has a partnership with them. It’s the first English language e-cinema. The NFB can transfer a film to us via the Internet. We upload it to the server and we can screen it anytime” in the inn’s digital theater, said Stanley. “There’s the potential for a guest to go to the website and request that we screen a particular film. It’s an exciting time.”

Some islanders work at the inn, and many interact with inn visitors through the Community Host Program (CHP). Program coordinator Sandra Cull admits the CHP is really a formalization of the custom of Newfoundlanders—befriending strangers. Her husband, a woodworker, made all the beds in the inn.

“We do what we’ve always done, only now it’s combined with a five-star inn,” said Cull. “The longer I do this, the more I realize it’s a valuable part of coming to Fogo Island. “What visitors do depends on their interest. Sometimes people say they want to do their own thing, and then the next day, they come to me because they’ve overheard what someone else is doing with a host, and they want to do it too.”

Guests may enlist a host to visit a woodworking shop, go aboard a long-liner, take a guided tour of the island’s communities, meet with a boatbuilder, visit an artist, or just have tea in someone’s kitchen. Guests might sign up to spend only an hour, but it usually turns into an afternoon, and often lunch or dinner.

“At this early stage, we have nearly forty people who act as hosts. We’re so lucky that a lot of them are retired, because it’s not a job,” said Cull. “Guests get a taste of the old ways, maybe learn the many uses for traditional punts in the museum in Seldom, or see the history of resettlement at the Fogo Island Marine Interpretation Centre.

“I get so caught up, my husband says, ‘You go to bed and dream about this.’ It’s true. It’s not just about hospitality, it’s about learning,” said Cull. “There’s a couple of ladies in the community—without much warning, I might call them up and say ‘Some guests think they’d like a partridgeberry jam tart,’ and they’ll do it.”

Aidan Penton is one of the community hosts. He’s a boatbuilder, fisherman, and woodworker. Oldest in a family of 13, himself a father of three, Penton is from Joe Batt’s Arm, one of the island villages. He’s also the guy who made all the light fixtures for the inn.

Five years ago he turning dropped caribou antlers on a lathe, making jewelry, letter openers, handles for ice cream scoops, wine bottle stoppers, rug hooks, and more, including the drawer handles for the bureaus he created for his own home. Penton also made the inn’s 400 lamps and sconces. It took nearly seven months, working 10 hours a day.

Making small items is good for the winter months when he’s not fishing.

“To carve a living out of Fogo Island, we have to do everything ourselves because we don’t make a lot of money,” said Penton. “We’re hunter-gatherers, and that occupies a lot of our time. We do our own work on the boat. I go moose and duck hunting. My wife is an avid berry-picker.

“We do a nice bit of cod—salt it and dry it—and the inn buys a lot of it. We dry ours on flakes,” a platform built on poles. “There’s a bit of a knack to it,” said Penton.

Often inn guests want to row one of the punts, go aboard his long-liner, or visit his boatbuilding shop.

He thinks the arrival of Shorefast and the Fogo Island Inn is a good thing: “It was time for us to catch a break.

FLAT EARTH OUTPOST

Host Clem Dwyer, a retired special education teacher, picked up a couple at the Gander airport in the fall, and asked why they chose Fogo. The husband said his wife wanted to celebrate her 30th birthday “far, far away.” Dwyer said, “That’s a phrase Zita uses, so that’s how they got here.” The Flat Earth Society calls Fogo Island one of its “four corners of the earth,” and a plaque at Brimstone Head in the town of Fogo proclaims it a “Flat Earth Outpost.”

His hometown, Tilting, has a residency for artists that predates the Shorefast arts program. Last year, he met two Maine fiber artists who spent six weeks on Fogo in the summer of 2013, then returned in November. “Now they’re coming back for six months.”

Textile artists Claudia Brahms and Noel Mount live in Hallowell, Maine. They’ve been traveling to Newfoundland for 10 years to spend two weeks hiking. When they heard about the Tilting residency, they applied. Both are weavers, and Mount is also a photographer.

Roy Dwyer, another community host, is a native of Fogo’s distinctly Irish community of Tilting, where the names, accents, and architecture still reflect its Irish heritage. He’s a fisherman, writer, poet, and storyteller.

“A lot of the old values and structures are gone from my great-grandfathers’ day,” said Dwyer. “In my generation, change is happening rapidly.” Tilting now hosts an annual Irish festival that sees up to 40 people from Ireland attending. Many have found relatives who emigrated generations ago buried in the Tilting cemetery.

Dwyer and others have turned to crab, shrimp, and turbot. Fishing now is financed by banks.

“They are ‘enterprises’ now—a new term, post-moratorium,” he said. “When they retire now, fishermen can sell the ‘enterprise’ and the license, and walk away with a million dollars. We have one of the largest offshore fishing fleets in Newfoundland.”

Some young people are moving back because they have landed jobs in the offshore oil industry.

“If you see a big house going up, those guys are working the supply boats for the oil rigs,” said Dwyer. “My nephew is on an Irving oil tanker, and he built a house next door to me. He works two months on and two months off.”

He’s optimistic about the future, figuring the world will always want more seafood. And the inn means “the world will be beating a path to our door, especially in summer. We’re not going to shrivel up.” While he thinks that the older islanders might not like every aspect of the new, varied economy, he adds that “without the new development, we would disappear.”

AMALGAMATION

In 2011, five existing municipal governments on the island amalgamated into one, called Fogo Island. Robert Greenwood is founding director of the Leslie Harris Centre of Regional Policy and Development at Memorial University in St. John’s.

“The province brought in incentives for communities to amalgamate, and Fogo did it. We encourage municipalities to pool their resources, because small communities with aging populations can’t do much by themselves,” Greenwood said.

Gerard Foley was the first elected mayor of the new Fogo Island town government. Before that he was supervisor of the Fogo Island co-op for 32 years. He likes volunteering to help keep the community viable.

“We want people to have a good experience on Fogo, and getting in and out is one of the challenges,” said Foley. Many residents feel the 60-car ferry will not accommodate an increase in tourism, and the additional trucks to deliver supplies. Already the co-op is dependent on the ferry to bring raw product in and finished product out.

However, as several residents point out, many people who travel to the inn arrive by helicopter.

Foley and his wife Darlene run Foley’s Place in Tilting, one of several new B&Bs on the island. Several years ago, there was only one.

“Fogo Island is one of the most popular destinations in Newfoundland now, because of the marketing done by the inn, and the publicity in all kinds of media,” said Foley. “We’ve seen people from all around the world at our B&B.”

Madonna Penton rescued her old family home in Joe Batt’s Arm. The 100-year-old house was abandoned for several years, and her uncle was selling it.

“He was afraid someone might take it down. He was pleased that I was interested. We did it up a bit. People starting calling—it was all word of mouth. Five years ago we officially made it into a B&B, Landwash Lodging. We don’t charge a barrel of money for the rooms,” she said.

“We have people from all over Europe, China, and Australia come here,” said Penton. “They are so inspired by what they see, they don’t want to leave. They want to buy houses. The people are wonderful.”

The tourists attracted to Fogo by the inn and Shorefast are giving the islanders new pride in their place and their crafts, said Penton. “We used to hate to see the icebergs come because they would make us cold. Now the tourists who travel the world come here to see them. I knew we had beautiful scenery, but we took it for granted. We didn’t think it would be appreciated by rich people from out of town.”

She went to school with Zita Cobb. “For all her money, if you saw her in a roomful of people, you’d never know. She’s done such good things for us. We’re so proud.”

Nadine Decker returned from the West Coast to Fogo to help create a comprehensive socioeconomic plan for the island. “I was tickled to come back to help, but it took longer than anyone expected. When the contract was up, it was time to leave, or find something else to do.” She bought one of the oldest homes in Joe Batt’s Arm and turned it into a guesthouse called Quintal House.

“I’m not a brave business owner. I looked at it for three years before I bought it,” said Decker. “The inn was going up, and my cousin had a café nearby.”

She says there are two camps regarding recent changes. “One camp is nervous about an entity with so much money. I don’t fear Ms. Cobb’s money, because she has a social conscience, and she responds to concerns,” said Decker. “The other money attracted by her money—that’s the part I fear.”

SEVEN SEASONS

Tourists go to Newfoundland primarily in summer, so Cobb said that after the inn’s “super” first season, she thought the inn might close for winter. Instead, she had an influx of families in the fall that surprised her.

Winter on Fogo “is not for the faint of heart,” she added. “We have seven seasons here: summer; berry season ; the storms of November, when the rocks are crying out for mercy; winter, with February’s wind; March ; April and May ; and June—the traitor. You can’t trust June; it’s neither spring nor summer. You can have all seven seasons in June.”

Some guests never leave the inn in the cold season—there’s plenty to do indoors, between the views from the beautiful rooms, the fine-dining restaurant, the theater, art gallery, library, and sauna.

But place is what the inn is all about, and Cobb wants to build community. “Fogo Island is woven back into the fabric of the world. We want to create a new kind of globalization, so that everyone is connected in a meaningful way.”