It’s 3:58 p.m. on Dec. 21, and the sun is about to set over Sears Island, the forested, causeway-connected spot in upper Penobscot Bay where we’ve come to observe the Winter Solstice. It’s cold out there—20-something degrees and windy—and we’re parked with others along the road leading to the island, watching the sun dip over Mack Point to the west.

The event we’re here for isn’t really the sunset but something called “Solstice by the Sea,” imagined and engineered by Friends of Sears Island, a conservation-minded group dedicated to protecting Sears Island in its current undeveloped state.

With a rumble from the mainland a Lucas Tree boom truck comes past us, heading onto the island, disappearing into the distance between the little lights the Friends have positioned along the road. The truck is heading, we hear from someone who inquired, for the tower at the other end of the island where the wind earlier this week has put a tree onto one of the guywires.

It’s a reminder that Sears Island, pristine as it appears to the casual viewer, isn’t that way at all—and hasn’t been for a couple of centuries.

The sky darkens. A bright, waxing moon and a planet—Jupiter—shine overhead. People climb out of their vehicles and gather around a warming fire.

Stephanie Holman, Belfast children’s librarian, tells a solstice folktale. A church group serves hot drinks and a food truck on the causeway sells more refreshments. An hour passes and we hear more readings including remarks from the Friends’ president, Susan White, and a Mary Oliver poem about a raven. By 6:30 the event’s mostly over; participants begin to depart as the longest night of the year gets underway and Sears Island is left to itself.

Not quite.

The state of Maine has plans for part of Sears Island: a facility from which to manage massive offshore wind-energy development designed to reduce New England’s historic reliance on fossil fuels. The wind-energy port would require clear-cutting and leveling a swath of the island’s forested western edge, along with the construction of a pier and other infrastructure on shore to stockpile and assemble the massive blades, towers, and other parts of the floating turbines Maine wants to site off its coast to meet its ambitious wind-energy goals.

A development on this scale would be controversial anywhere in Maine, where refineries, ports, mines, nuclear power plants, dams, and resort developments have been proposed over the years, but few have been built.

Ask why this is the case and you’ll hear every reason from economics (“no reason to build it here; too much competition elsewhere”) to the environment (“keep Maine pristine”), to elitism (“no one cares about the jobs these projects could provide”).

An offshore wind port on Sears Island could be counted on to draw forth all these arguments and more, and like other proposals, successful and otherwise, it has begotten its share of friends and enemies since it was proposed over two years ago.

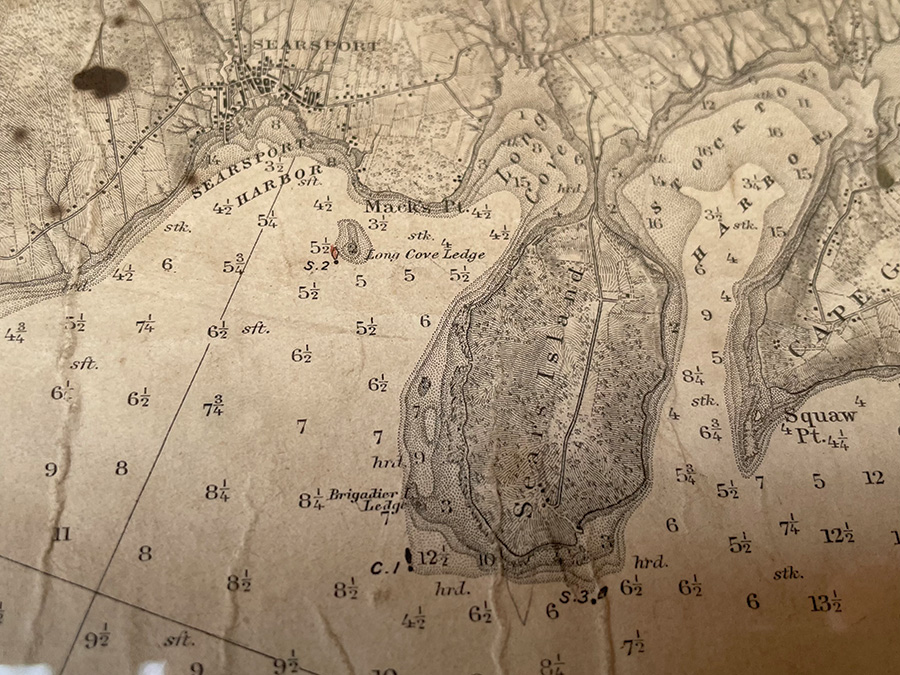

Sears Island sits in the midst of a region—the lower Penobscot River and upper Penobscot Bay—where maritime and industrial development have flourished for a couple of centuries. Upriver, Bangor was one of the world’s biggest lumber ports in the mid-19th century.

Down the bay, Belfast thrived from shipbuilding and shipping during and after the Civil War. Massive granite quarries were developed at Mount Waldo, Vinalhaven, and numerous islands in Penobscot Bay. Rockland mined and refined vast quantities of lime. The inshore lobster fishery thrived, as did canneries processing herring.

Lumber, stone, lime, and fish all moved south on the bay, headed for the world’s markets. At one time Searsport, the town in which Sears Island lies at the mouth of the Penobscot, was home to many prominent sea captains whose houses dominate its streets today.

But Sears Island itself remained relatively undeveloped during the 19th century, perhaps because other places better suited industries’ purposes. In fact, George S. Wasson and Lincoln Colcord’s classic Sailing Days on the Penobscot, one of the region’s most complete histories of that era, never mentions the island at all.

When Wasson and Colcord published their book in 1932, the region’s sailing heyday was in decline. Transportation was moving to railroads and highways. Except for a hotel built in 1906 near where the Sears Island causeway is today—“the complex included the Bar Point House, which had a verandah all around it, a dance pavilion, a merry-go-round and athletic fields nearby,” reported the Industrial Journal at the time—Sears Island would stay quiet for another five decades.

The little resort, which was out of business by the late 1920s, was something of a harbinger: it was “an offspring of the new Bangor and Aroostook Railroad’s Northern Seaport line to Searsport,” stated the Industrial Journal.

If anything would eventually stimulate interest in proposals to develop Sears Island, it was this proximity to the railroad, and the B&A’s real estate arm, Bangor Investment Company, which acquired the island in 1905.

Just why the railroad wanted to own the island isn’t entirely clear, except for suggestions that it might become one of the many summer developments sprouting along the Maine coast. Given the B&A’s activities on the nearby mainland including a “coal pocket” at Mack Point in Searsport (coal for paper mills in northern Maine and domestic heating in Bangor came there by ship and then moved on by rail), owning the island may have simply seemed wiser than not owning it. At any rate, for the next 70 years or so, through the Depression and two world wars, Sears Island sat there, a few farm buildings collapsing into their cellars while fields reverted to forest.

Things began to change in the late 1960s. Oil refineries were proposed for Machias, Eastport, and Long Island in Casco Bay near Portland. All were as controversial as might be expected, pitting the pro-development community against fishermen and Maine’s nascent environmental movement.

Among the first ideas to surface for Sears Island wasn’t a refinery but an aluminum smelter, followed by a nuclear power plant.

“Tepco Eyeing River Isle For Plant,” was the headline on a story in the Bangor Daily News in April 1969, revealing what had been rumored for some time: rejection elsewhere had made Sears Island a target for industrial development.

“Officials of Tepco Inc still seeking a site in Maine for an aluminum smelter,” the 1969 BDN piece continued, “were understood to have met with Searsport Port Committee members Tuesday at Jed’s Restaurant here to discuss the possible use of Sears Island in the harbor.”

Then the BDN’s writer gets a bit cute:

“In customary quietness, however, there was no word from the gathering other than that the group met to discuss the promotion of industry in the port, according to Bill Abbott, president of the port committee. Since voters at Trenton turned down the proposed aluminum smelter in a 2,000-acre industrial park, the Tepco people have been reported considering various coastal areas as possible sites for atomic power and aluminum smelting plants.

“The company has however run into opposition at most sites which has led some persons to believe that offshore islands offer better locales for such smelters. It was suggested at one time that offshore islands of St. George [south of Rockland] might be feasible but were overruled by the expense factor in building granite causeways. Sears Island can be reached by foot at low tide.”

Oil came next: in 1971, a company calling itself Maine Clean Fuels proposed buying Sears Island (where an industrial park had been proposed by the railroad) and building a plant to remove the sulphur from oil destined for Boston.

The desulphurization plant didn’t fly; nor did Central Maine Power’s proposed nuclear power plant when an earthquake-vulnerable geologic fault was discovered in 1975.

Next came a coal-fired power plant (much opposition; never built) and a state-sponsored container port that foundered on environmental grounds in the 1980s.

Sears became something less than a true island in 1988, when the Maine Department of Transportation (by this time the state had taken possession of the island) began constructing the causeway that today connects it to the Searsport shore. Broad and straight, the causeway allows heavy trucks to reach the island at all times, making it easier to build—or so the administration of Gov. Angus King hoped—its proposed six-berth container port. But like earlier projects the container port didn’t materialize, partly because of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s concern over eelgrass. (If you followed the port case at the time you’ll remember King’s sneering characterization: “e-e-e-e-l grass,”—long-e’s included—he said over and over at the time.)

Even with its new, truck-friendly connection to the mainland, Sears Island continued to sit there, undeveloped. The state agreed to a 601-acre conservation easement protecting most of the island, but reserved 335 acres along the western shore for other purposes.

Meanwhile Maine was changing. The pandemic that swept over the world in 2020 transformed economies in much of the world including the U.S.

Patterns of work changed, as did attitudes toward traditional jobs, their value to society, and who should benefit from any job-creating project. Most importantly, whole new ways of working—remotely or on computerized assembly lines, in containerized loading systems, in an economy where anything could be manufactured practically anywhere—were replacing more traditional jobs everywhere. In Maine these changes were profound, as papermaking, shoe stitching, shirt making and a dozen other specialties that had supported people for generations declined or disappeared.

In Searsport, where unionized longshoremen had handled inbound bulk cargoes and outgoing paper shipments as recently as the 1960s, the system changed to roll-on, roll-off containers that didn’t require a lot of longshoremen. At Millinocket, a hundred miles up the Penobscot, Great Northern Paper’s plan to build a dam it claimed would save 1,600 jobs foundered when a shrinking paper market, new energy-saving technologies, and competing uses for the river ganged up on the company. Today the mills at Millinocket and East Millinocket that once employed nearly 2,000 people are gone. Shoe companies, shirt manufacturers, and specialty wood products makers are largely gone too, victims of changing markets, new technologies, overseas competition, and customer tastes.

Big as these transformations were for Maine and other places, they’ll likely prove less significant than something even bigger: climate change. Human beings worldwide have powered civilization for centuries by burning fossil fuels—coal and oil for the most part—and in the 21st century, it’s becoming clear that all the burning must be paid for. Planet Earth is warming at alarming rates; polar icecaps are melting faster than scientists thought they would; sea levels are rising noticeably everywhere including the Maine coast; the routes of ocean currents are shifting; storms are becoming more damaging and dangerous.

Three successive storms in December and January, in fact, graphically demonstrated the Maine coast’s vulnerability by washing out roads, flooding towns, and destroying harborfront infrastructure from Kittery to Eastport. Sears Island—as yet undeveloped—didn’t suffer, but waterfronts elsewhere in Penobscot Bay did.

So, perhaps inevitably, Sears Island, long the focus of disputes over what to do with it, becomes the scene of a new debate: whether to enlist this state-owned property in the effort to replace the fossil fuels that caused climate change in the first place. Jobs will be a factor in this new argument, but they’ll take second place to climate change and how we’re all going to deal with it.

The New England coast, offshore at least, is a windy-enough place to have already attracted big projects off Rhode Island and the eastern end of Long Island Sound. The projects are massive—we’re talking about towers 50 stories high with blades a hundred yards long—and must be partly assembled ashore and partly in place.

The proposed Maine project is being coordinated by the Maine Port Authority, whose executive director, Matt Burns, outlined four different plans under consideration last year: Sears Island itself, Mack Point on the mainland, a “hybrid” design combining both places, or not building the port at all.

Accustomed to dustups over its undeveloped but causeway-

connected island at the head of Penobscot Bay, the state convened an Offshore Wind Port Advisory Group that first met in July 2022. Members included representatives of all interests and persuasions, from Searsport residents to state officials, from development advocates to environmental groups.

Maine Audubon, the Sierra Club, the Labor Climate Council, the Maine Port Authority, Friends of Sears Island, Sprague Energy, the town of Searsport, Maine Conservation Voters, and the Islesboro Islands Trust were all invited and took part in six meetings in Searsport, Orono, and Augusta. There were tours of the Advanced Structures and Composites Center at the University of Maine to look at floating turbine foundations developed there; and tours of the two Searsport locations as well as a tour of Estes Head in Eastport, another location that was eventually eliminated.

All in all, little in the public record of the Wind Port Advisory Group suggests that any minds were changed.

On Feb. 21, the state announced its decision: locate and build its offshore wind port on Sears Island. Proponents cheered the choice as an important step in Maine’s effort to free itself of fossil fuels; opponents questioned the state’s plan on environmental grounds and because they consider Mack Point the better alternative.

Gov. Janet Mills, in making the announcement at the State House in Augusta, “touted the need to generate wind power to fight climate change while boosting skilled manufacturing jobs.”

So once again, Sears Island finds itself at the center of things.

Some examples:

The Conservation Law Foundation supported wind port development on Sears Island over Mack Point in a September op-ed in the Portland Press Herald, arguing the island would be the “least expensive site to develop” and wouldn’t involve the dredging required at Mack Point.

The Maine Chapter of the Sierra Club supports the Mack Point location, as does Sprague Energy, which currently operates an oil terminal there.

Maine Audubon and the Natural Resources Council of Maine, two large environmental organizations that might be expected to weigh in, have already participated in discussions but have gone no further on where to locate a wind port. The same can be said of the Maine Labor Climate Council, which strongly supports building a port, but hasn’t taken a stand on Sears Island vs. Mack Point.

The Bangor Daily News, which has covered Sears Island and all of its would-be developers for years, came out in support of an island location for the wind port in January 2024.

“Port facilities to support Maine’s nascent offshore wind industry are very far from fruition,” the editorial stated, “but pursuing them on Sears Island could meet a decades-old goal for the state-owned land, while helping Maine meet some of its climate and economic goals.”

Locating the wind port on Sears Island is favored by those concerned about the cost and environmental impact of dredging off Mack Point. Advocates of re-purposing the existing “brownfield” site at Mack Point (currently an oil facility) favor using that site instead. The Friends of Sears Island, which has devoted time and energy into making it into an attractive, park-like place for outdoor recreation, strongly opposes clearing part of the island’s forest, even if it’s allowed under the current conservation easement.

As always seems to happen in debates over the use of public resources, there’s the unexpected twist: in Sears Island’s case, the presence of sand dunes. Dunes have been protected under state law for decades. On Sears Island a dune system that developed after a jetty was built in connection with the uncompleted cargo port project might fall under this law.

Anticipating a problem, the Mills administration proposed a legislative fix to exempt this particular dune from protection, which won approval in April.

The state remains determined to move away from fossil fuels and develop its offshore wind resource. Any result is likely to end up in court as opponents and advocates on both sides of the debate “lawyer up” and sue. Litigation means delay. Literally and perhaps figuratively, the seas around Sears Island continue to rise.

Given Sears Island’s long history of failed projects, of course, an announcement—even by the governor—is, once again, a statement of intent to do something. The Bangor and Aroostook Railroad, former Gov. Angus King, Central Maine Power Co., Maine Clean Fuels, Tepco, and the Friends of Sears Island have all announced their intentions and preferences for Sears Island as well. For a variety of reasons none have come to pass.

Over the years, sometimes in response to all the ideas for it, the island has changed in a few ways: its fields have become forests; it’s now connected by the state-built causeway to the mainland; most of the island is now protected by a conservation easement; the 100 acres outside the easement is now reserved for purposes that could include the offshore wind port.

In February, not long before the governor made her announcement, the world’s most famous groundhog made his, predicting an early spring in 2024. Since then we’ve had another serious coastal storm. Forty percent of the time, it’s said, the groundhog’s right.

David D. Platt is former editor of Island Journal. During a forty-year career in the Maine media he wrote many stories about Sears Island and proposals for its development.