The power is out on half of Chebeague Island. Most toilets aren’t flushing and a few roads have downed trees across them, but the high winds haven’t stopped the boats from running.

At the ferry landing, Suhail Bisharat stands with his hands behind his back, smartly dressed and smiling warmly. He greets Clint Jones—a mechanic from Cumberland who regularly comes over to work on island cars—and they make a plan for him to swing by later and figure out why the Bisharats’ Audi is leaking coolant. They lean in close to hear what each other is saying, the wind blowing their white hair in tangles.

Arriving on Chebeague for the first time over 40 years ago, people were very curious about Bisharat. Fresh off a flight from Jordan and delivered to a tiny dock in Maine for his soon-to-be-wife’s brother’s wedding, there was no hiding his being from another part of the world: if his appearance didn’t give him away, his accent surely did.

When one woman on the ferry ride over inquired if he was from away, he told her, tongue firmly in cheek, “Madam, I am not only from away, but from far, far away.”

Bisharat seems perfectly at ease talking to anyone. If he sees an unfamiliar face at Doughty’s Market or on the boat, he’ll make it a point to introduce himself and then, as if performing a magic trick, they are the best of friends. He’s curious about people and genuinely interested in what they have to say.

“Coming from different cultures—Cairo, England, Saudi Arabia, Amman—I knew how to be around lots of different people,” he says. “I’ll always be an outsider on the island, even to this day. But I was never intimidated. I just remained myself all this time. I never tried to wear Maine clothes and my accent is still what it’s always been. And the community accepted me for who I really am. I think my Egyptian humor helped, too.”

Bisharat was born in Amman, Jordan’s capital, the youngest of three brothers from a multi-generational family of farmers. As a young man during World War I, his father helped supply the British and Australian armies with horses and he developed these relationships into large-scale contracting, such as road building and investing in new businesses in Lebanon and Egypt. He decided after World War II, when Suhail was six years old, to move his family to Egypt where his sons could attend the British School. They grew up in a cosmopolitan Cairo that all but disappeared with the 1952 revolution and the toppling of the monarchy.

“I always say I had a happy childhood, but how could I have been happy with Nasser’s revolution, the king being overthrown, the Suez war?” he says. “But I was a kid on a bicycle, in boarding school, and going to dances. What did I know?”

The family was forced to leave the country but Bisharat was sent to London University where he studied geology.

There was something about being outdoors among minerals, sketching, collecting rocks—it fascinated him. And during those early boom times of large-scale oil production in the Middle East, it wasn’t long before he was tapped for jobs working on rigs in the North Sea and the deserts of Saudi Arabia.

He used to wake up at five in the morning and send coded messages to the Aramco headquarters to report on how drilling was going. Often, he was the only geologist working 24/7 for two weeks and if he was sleeping while drillers dug into certain zones without it being analyzed, it was grounds for being fired. His first order of business was to make friends with drillers, giving them gifts and finding time to joke around.

“There was a guy called Big Red, who’d been digging for 20 years,” Bisharat remembers. “He said, ‘Sam’—he used to call me Sam—‘anytime I find something, I will stop and wake you up.’ And he did. These are little things you have to learn, how to be with people. I learned good management on those rigs. It’s what made me transfer into the arts.”

After working for the oil companies, he returned to Jordan in 1978 and bought a building in downtown Amman that needed renovation but had an incredible view of the citadel. In the basement, he opened a “very humble” gallery of Jordanian art and every Saturday night he would host artists, poets, and writers. It slowly became the place to be.

Two years later, he got a telephone call from the president of the Royal Society of Fine Arts, Her Royal Highness Princess Wijdan, asking if he would be interested in establishing Jordan’s first National Gallery of Fine Arts.

“It was a life changing call,” he says. “And Queen Noor was the patron, so how could I say no?”

Yet when asked if he considers himself an art scholar, Bisharat laughs and claps his hands. He hadn’t studied art history or Islamic art, but growing up in Egypt brought him in contact with art.

The earliest museums in the Arab world often focused on archaeology and antiquities, so the gallery was really the first of its kind, boasting a unique collection of work by contemporary artists from Jordan and elsewhere in the Middle East. Everyone who came to Jordan and met the king and queen would be sent to the National Gallery. This included Queen Silvia of Sweden, whose husband King Gustaf would later present Bisharat with the decoration of “Commander of the Polar Star” for his contributions to building intercultural exchange and understanding through the arts. But most importantly to Bisharat, the Jordanian artists he worked with felt they were being recognized and respected for the first time.

At the Bisharat’s house along the south shore of the island, a generator steadily hums. Suhail sips coffee and his wife, Leila, opens her laptop.

“Oh no,” Leila says.

“What’s wrong?” Suhail asks, looking up from photos of his travels.

She reads a headline reporting that over a hundred people waiting for aid in Gaza have been killed after Israeli forces opened fire, causing a massive stampede.

“I’ve worked in so many conflict situations over the years,” she says. “But nothing as horrendous as this.”

Leila spent much of her career as a representative for UNICEF—the United Nations children’s fund—in the Middle East, finding solutions for children who were often in dire straits, including war zones. She hadn’t intended to start her professional life in the Middle East, but as happens, one thing led to another.

After receiving her doctorate in Middle Eastern studies from Princeton University—where she grew up and where her father, Blanchard Bates, was a longtime professor of Romance languages—an opportunity to work in Cairo presented itself. It was supposed to be a year appointment, but she was hooked. Two years later, she was offered a position in Amman and it was there she met Suhail.

After seeing Suhail at numerous dinners and events where “he only was ever interested in looking at paintings on the wall,” she remembers, they wound up dancing all night at a club. As a divorced and single mother of two, it wasn’t lost on Leila what being seen with a man in public like that meant in a largely Islamic community. But their relationship blossomed, and they were married two years later.

“It was the best thing to happen in my life, to marry Leila,” Suhail says, smiling at her. “When we met, it wasn’t necessarily love at first sight. It was a deep appreciation for what the other was doing.”

The Bisharats left Jordan, and the gallery, in 1993 when Leila took on a new position as the head of planning and programs for UNICEF in New York. They raised their youngest daughter, Nora, in the city, with holidays and

summers on Chebeague.

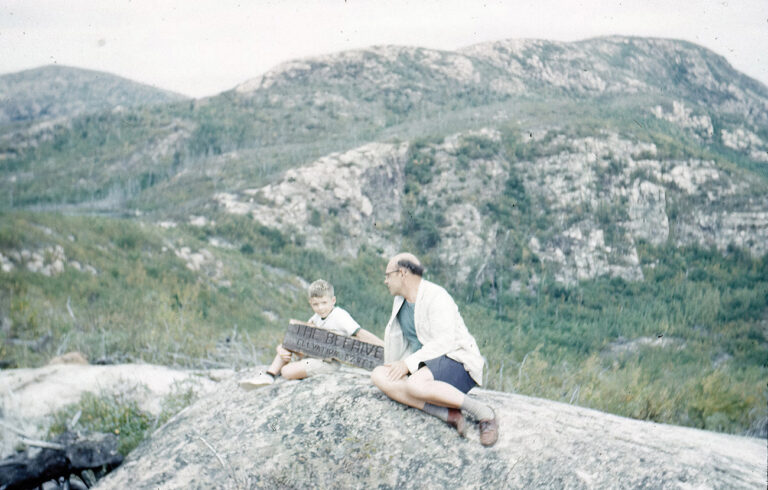

At six years old, Nora wanted to ride her bike around Manhattan in the same way that Maine island kids did and she longed for that freedom. With Leila’s deep connection to the island—her father’s family were among its earliest settlers—Suhail pushed for living more full-time on Chebeague until their next international posting, with Leila commuting back and forth and Nora attending the Chebeague Island School where Suhail coached the soccer team.

The commuting solution was tough on Suhail and Leila, but Suhail’s flexibility, self-confidence, and sense of humor, Leila says, helped buoy them “over all kinds of challenges in war times and in peace times.” They eventually settled there year-round in 2002, building a new house down the hill from where she played during summers as a child.

“It was absolutely the right decision to share this place with our kids,” Leila says. “We both wake up each morning, look out over Casco Bay and say to each other how fortunate we are to be at home together on Chebeague.”

In a clearing of the Littlefield Woods, where a giant horse chestnut tree towers over him, Suhail stretches his arms wide and looks up. “It is like walking into a cathedral!” he exclaims. “And especially on calmer days, it’s amazing to listen closely to the trees rubbing together and all the vibrations.”

Just shy of 25 acres, this parcel of land sits in the middle of the island and has been where islanders have walked for centuries. It also plays an important role in being home to Chebeague’s sole aquifer, the source of drinking water for the island.

The Bisharats have been stewards of these woods since 1984, taking over from Leila’s father, who helped found the Chebeague and Cumberland Land Trust. After a massive fundraising effort, the land trust bought the property from Suhail and Leila, effectively protecting it in perpetuity.

“Coming from a part of the world where access to water is an issue and there are very few trees, caring for these woods feels like the most important thing to do,” Suhail says. “I’m so honored to be part of this family and carry on what my father-in-law started.”

Being deeply involved in all aspects of the island started right away for Suhail. In the early years of acclimating to island life, he was approached by Donna Damon, long-time head of the Chebeague Historical Society, and asked if he’d consider serving on the board. He graciously accepted and during their annual meeting in 1998, he gave a lecture on how Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt impacted Egyptian antiquities.

It ignited a monumental, but not impossible, idea: could he plan an art-focused trip to Egypt as a fundraiser for the historical society for a group of islanders?

After much research and logistics, what came to be known as the “Chebeague 20” arrived in Egypt 200 years after Napoleon’s initial expedition. Bisharat had arranged for the best hotels, visits to the pyramids, cruises on the Nile—all while keeping islander budgets in mind.

“The excitement was tremendous,” he says. “They all bonded and followed rules as if boarding a Chebeague Transportation Company boat, on time and with lots of stories to tell.”

The trip raised a bundle of money for the new museum on Chebeague and travelers came back fired up and ready for more. So another trip was developed, this time to Jordan where islanders went behind the scenes to see how scholars piece together hundreds of broken shards of ancient artifacts.

And then to Turkey with a visit to the famous Hagia Sophia mosque where they were treated to a private concert of Sufi and Turkish medieval music. And another trip to the Greek islands. All told, Bisharat organized 15 trips since 1999, with over 100 people from the island traveling.

There is now a popular theory that there is a higher percentage of people on Chebeague who had direct contact with the Middle East than anywhere else in the country.

“It was an incredible chance to bond as a community somewhere that wasn’t the island,” he says. “It was also important to me that people experienced the culture that produced all these wonderful artifacts. And they saw where I came from and understood me better.”

Bisharat puts down his spoon after the last bite of mahalabia—a Middle Eastern pudding made from semolina and milk, garnished with crushed pistachios and rose water—and gazes out on Casco Bay, letting out a contented sigh. The generator has been turned off and the wind has died down enough where the whole house is still. Outside, Canada geese root around for worms and through the floor-to-ceiling windows it’s like watching a performance.

“It’s like a variety show,” he says. “You don’t know what will be showing up next: a diving seagull, a bending tree, diamonds on the water in the morning, shimmering.”

This time of year is Bisharat’s favorite. He loves the quiet and walking the island to sit on neighbors’ porches, their houses dark and empty while they’re in Philadelphia or Boston. He’ll text them “Wish you were here!” But he gets excited thinking about seeing many of his friends again.

“I think I always have projects in mind, but I think I’ve reached the stage in my life where I feel I’ve done what I needed to do,” Suhail says. “It took a lot of courage to cut the umbilical cord of home and the Middle East is with me—music, art, desserts—but I reinvented it to make it more accessible to the present. Not regretting or living in the past, but making it flow.”

Scott Sell is an independent multimedia producer and writer living in Rockland. He served as an Island Institute Fellow on Frenchboro from 2006 to 2008 and was the Island Institute’s media specialist for several years.