In the late 1800s, biology was becoming a real science and profession. The discoveries of Alexander Humboldt, the publication of Darwin’s The Origin of Species, and the classification work of Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz had spurred interest in diversity and evolution.

One place where biologists could easily access many life forms was the marine environment. At the turn of the 19th century, marine research stations were being set up all over the world. One of them, the Tufts Summer School of Biology, opened at Potts Point in South Harpswell on Casco Bay in 1898. The first summer, eight students and their teachers hauled seawater half a mile to a small cottage that served as laboratory and dorm.

In 1920, affluent Bostonian George B. Dorr, the main driver behind the creation of Acadia National Park, decided there should be a marine research station on Mount Desert Island. He knew about the South Harpswell laboratory and came up with a plan to move it to the former Thomas Emery Farm in Salisbury Cove. He touted the property’s beneficial qualities: “good wharfage opportunity, its picturesque character, its old farmhouse and the pure water…coming in a deep continuous channel from the open sea.”

The station would be a place for scientists to go in the summer to study marine organisms. Dorr felt the station would provide “a delightful contrast to Bar Harbor’s fashionable life.”

In fact, the arrangement aligned with the well-established rusticator tradition whereby college presidents, clergy, industrialists and other esteemed and well-off individuals and their families spent their summers on the island in retreat from East Coast cities. As Charles Eliot, president of Harvard put it, the scientists would be “invigorated, ready to do more valuable work the whole winter through in consequence of this climate boon and stimulating change.”

In recounting the history of the lab—which became The MDI Biological Laboratory—Jerilyn Bowers, its development officer, explains how the physician-scientists who arrived in the 1920s and 1930s believed that marine organisms might help them address medical challenges. Physiologist Eli Kennerly Marshall (1889-1966), for example, wanted to understand how the body could retain drugs longer and thereby increase their effectiveness. In studying the physiology of the kidney, he discovered that certain fish had complex filtration units. His studies of goosefish, caught in nearby waters, led to a new understanding of how the kidney functions.

Because the lab attracted scientists from around the world, the research was varied. One avenue of interest was environmental issues, including the effects of DDT and other toxins on fish and the impact of crude oil on sea birds. The underlying theme of the research is “finding the right model, whatever that is, to answer the question you are seeking to answer,” Bowers said.

End of Vacation Science

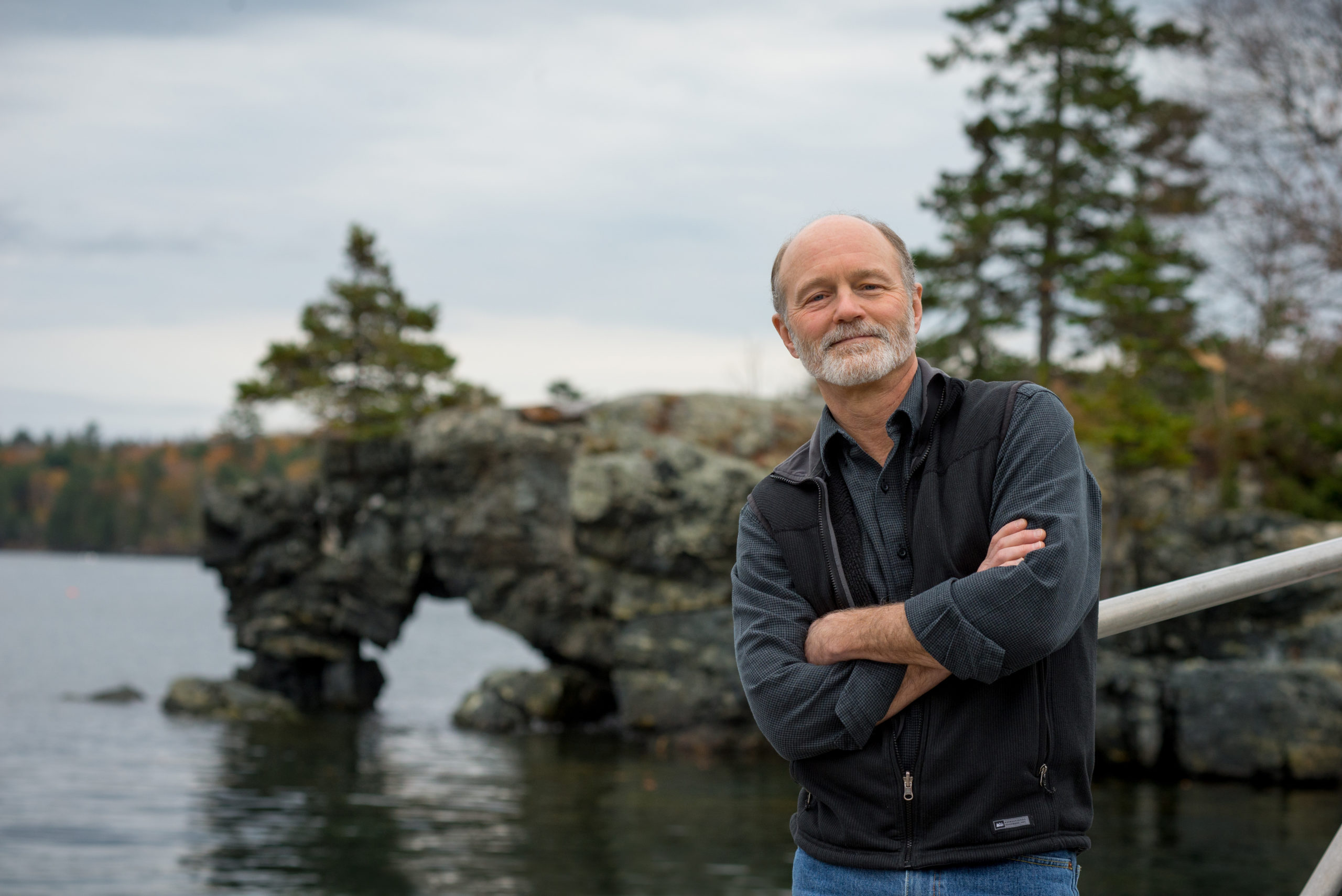

The model of doing research where scientists would pack up and go away for a summer of study started “dying very rapidly in the 1980s,” notes Kevin Strange, Ph.D., MDI Bio Lab’s president since 2009. Indeed, the lab moved to a year-round operation in 2000. And while the research facility remains by the water—fronting on Upper Frenchman Bay—its connection to the marine environment has decreased in the last 20 or so years.

The setting remains important, however. “Rather than doing science in a bunker somewhere in the middle of a big city,” says Strange, the lab is “keeping people connected to the natural world,” a connection he feels has been lost in the biomedical sciences.

While biologists can still learn a great deal from marine organisms, Strange points to economic realities to explain the lab’s shift away from the sea at its doorstep. Not long after arriving at the lab, he asked his team to review all the National Institutes of Health grants using search terms related to marine organisms. Out of 35,000, they came up with 25.

Faced with this state of affairs, the lab sought to diversify its revenues, in part by finding ways to commercialize its work. Many marine labs are adopting this strategy to survive. The Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in Boothbay, for example, has taken up algae production. Its National Center for Marine Algae and Microbiota is a leading distributor of marine microalgae for science and industry.

In 2013, MDI Bio Lab spun off a for-profit company, Novo Biosciences, Inc., based on a molecular chemical compound, MSI-1436. First discovered by Michael Zasloff, M.D., Ph.D. in the dogfish shark on a visit to the lab in the 1990s, the compound has been shown to facilitate dramatic repair and hasten regeneration of complex limb tissues and heart muscle. Novo Biosciences received a major NIH Small Business Innovative Research grant in 2017 to take the drug candidate to the next stage, testing for commercialization.

“A lot of the stuff that we’re doing with industry—companies incubating on campus, trying to form our own companies where it makes both economic and strategic sense—that was a dirty word 20 years ago,” Strange says, “but it’s the reality of the world and it’s the right thing to do, too.” He points out that the lab is funded by the National Institutes of Health, not the National Academy of Sciences. “There’s a balance between pure discovery and where that discovery might have real applications,” he avers, “and the trick is finding that balance.”

“We’re not studying stem cells,” Strange explains, “We’re studying the animals that live in nature that have phenomenal regenerative capacities.” Among those creatures are the zebrafish and the axolotl, a kind of salamander. Both have the amazing capacity to regenerate lost body parts.

Voot Yin, Ph.D. and other scientists at the lab have been studying these creatures to learn how regeneration works and how to trigger a similar mechanism in humans.

The lab produces most of its own test animals. Animal care technician Karlee Markovich shows a visitor immaculate incubating facilities where the tiny creatures are raised. The animals reproduce quickly in captivity and are relatively inexpensive to house and utilize.

Strange and his team remain realistic about finding a breakthrough. “If you had a heart attack and you could reduce the amount of scar tissue by 5 percent,” Strange explains, “you’d be doing handsprings.” If the new drug works, it would also have potential applications for MS, spinal cord regeneration, and burn healing.

Education Central

“The Laboratory is a place for study and investigation, not for teaching,” wrote George B. Dorr at its inception. But today, education is a core part of its mission. The lab prides itself on its hands-on approach, offering 30 to 35 courses each year, training everyone from middle school students to practicing physicians and scientists. “It’s an important part of our economic diversification,” says Strange.

The lab is not interested in training more bench scientists. “We really focus on what people can do with a science education, whether in business, politics, law—you name it.”

This effort relates to a bigger push to produce a more scientifically literate society, and to place knowledgeable people in decision-making positions. “We’re living in a period where science doesn’t seem to matter much,” he states. “We have an Administration that has no interest in science, and wants to remove it from every discussion it possibly can.” Nevertheless, Strange believes science will “always prevail because it’s the way to understand the world around you.”

The lab enjoys close relationships with a dozen research and educational institutions across the state, including the Jackson Laboratory and College of the Atlantic, both on MDI. The collaboration aims to develop a technically skilled workforce through biomedical research training for undergraduates; provide research support to young faculty to increase their competitiveness for federal biomedical research grants; and improve Maine’s research infrastructure through a network of core facilities with state-of-the-art equipment.

“Young people coming up now have a much broader perspective of science,” says Strange. “They’re not going to go off into an ivory tower somewhere and close the door; they want to solve problems.” The lab initiated a one-week course last summer, “Bridging Disciplines: Navigating Successful 21st Century Careers in Biomedical Science,” inspired by a couple of University of Maine students who recognized the need for cross-disciplinary training to keep their studies relevant in a rapidly changing job market.

The lab has embraced the STEM movement and the increasing focus on entrepreneurship. At the same time, Senior Staff Scientist Jane Disney, Ph.D., the lab’s director of education, has been leading the effort to train citizen scientists. “We’re trying to instill a sense of place in students,” she explains, so that they return home with the tools to test and measure. “People learn better when they have something invested in the data they’re developing,” she says.

The lab offers special summer programs to engage and educate visitors. For several years, it mounted exhibitions highlighting connections between art and science. Last year four artists were “embedded” in the lab.

Additionally, the lab has increased its contribution to local, regional, and state economies. The lab has built two new facilities in recent years, using all Maine labor. Many of its 62 full-time employees live on Mount Desert Island. While the nearby Jackson Laboratory boasts a much larger work force, Strange believes that for its size the MDI Bio Lab has “a very substantial impact on this economy.”

He also insists that science and technology can “drive a robust economy.” He points to Maine’s “remarkable” number of R&D assets. Although the state lacks a long-term strategic plan to build on these assets, he sees no reason why it can’t be a regional leader in the field, considering its proximity to Boston. A $3 million bond issue approved by voters in 2014 allowed the lab to modernize and expand its infrastructure, which includes a new building, the Maine Center for Biomedical Innovation.

Asked where he’d like to see the lab in ten years, Strange first addresses capacity: “We need more scientists.” While the lab should stay small enough to be able to adapt and move quickly, he notes, it needs to be larger, with “more people colliding with each other.”

One of those colliders, Aric Rogers, Ph.D., left his career as a meteorologist after seeing a special on television about the genetics of aging.

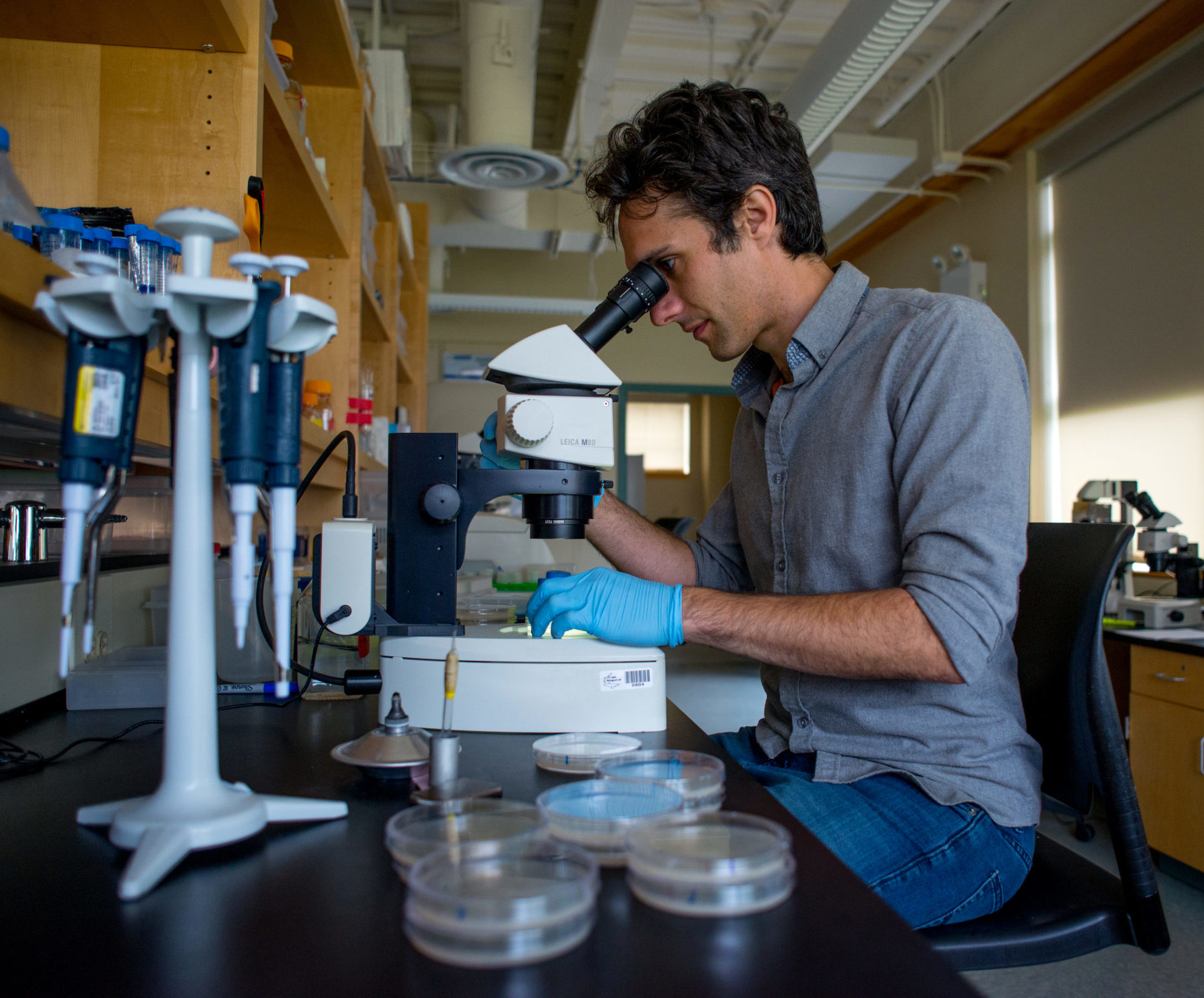

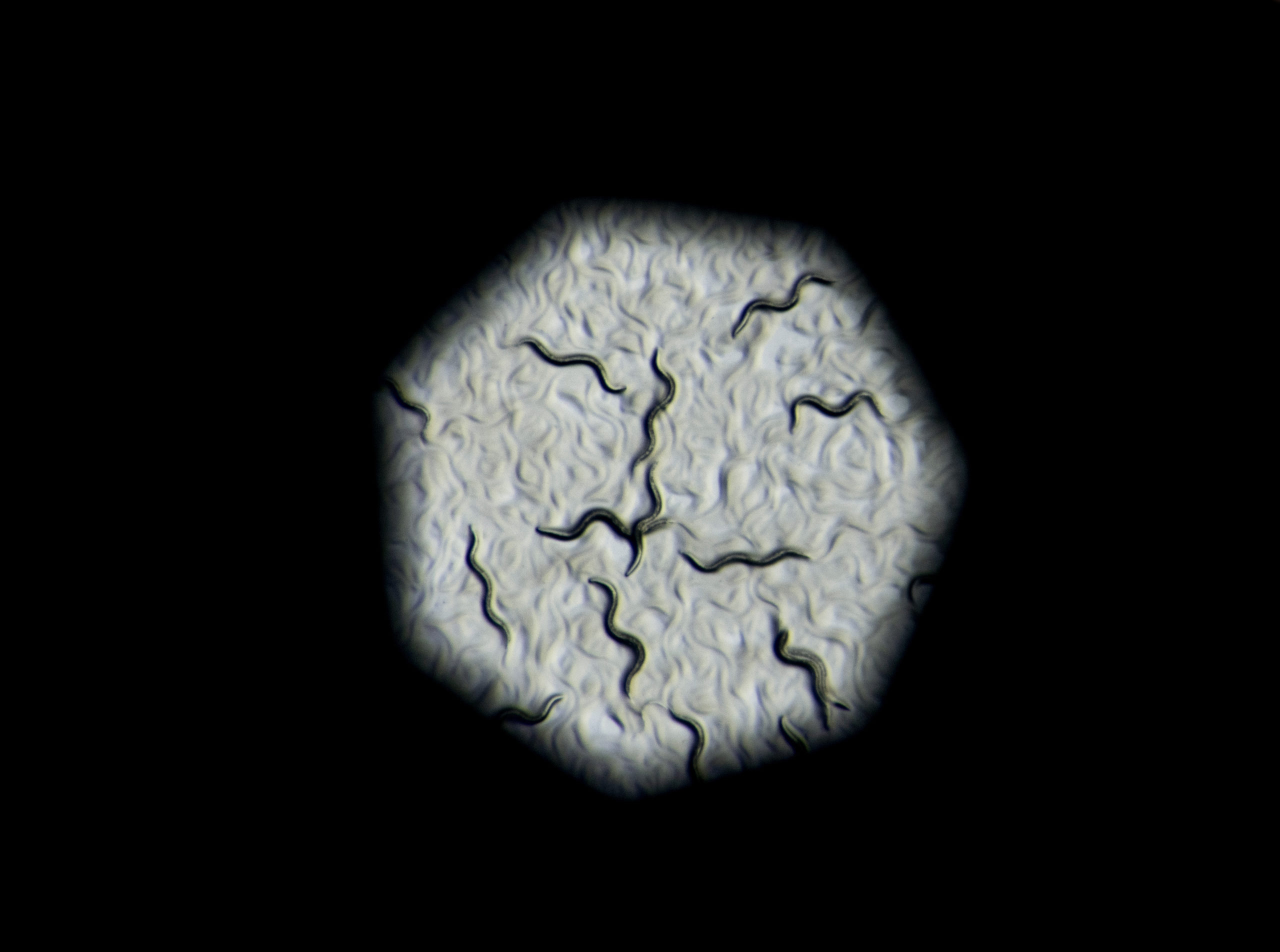

“I was fascinated by the incredible discoveries that were being made in many different animal species,” he recalls. After completing post-doctorate research at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging in California, he made his way to the MDI Bio Lab where he works with C. elegans, a roundworm nematode the size of a grain of rice. His goal? To find new therapies that slow aging and prevent or treat age-related illnesses in humans.

As the MDI Biological Laboratory moves further into its second century, it remains the laboratory by the sea, but its mission has expanded. With support from the NIH, the Maine Technology Institute, and other funders, the lab is now recognized as a world leader in regenerative and aging biology and medicine research. From the beginning, the lab was clear in its focus: advance human health. Its current commitment to anti-aging and regenerative strategies takes this focus to a new and exciting level.