Some are born to the island life; others arrive on an island and feel like it is a place they know by heart. On a beautiful fall day last October, Beverly Johnson began relating the story of how she came to Chebeague Island as a teenager as we stalked a pair of nondescript brownish birds on the shore that she had not seen before. Crouching down in the wind with camera in hand, pieces of Beverly’s improbable journey come into focus.

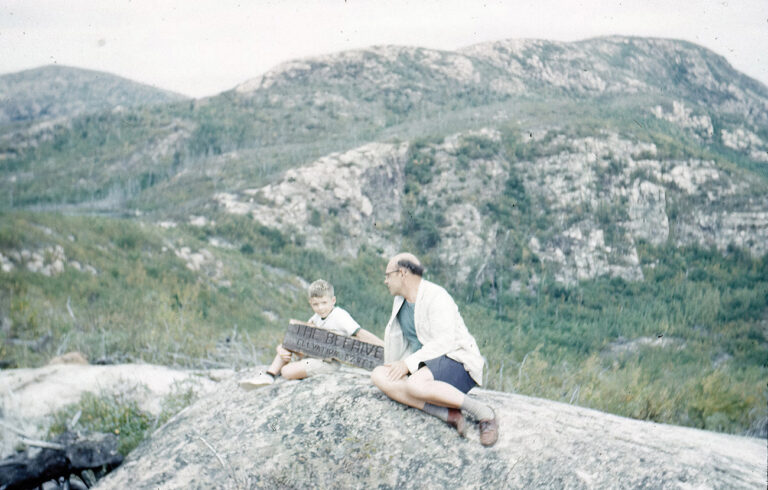

Beverly Ross, now Beverly Johnson, did not grow up on Chebeague, but came to the island with her father, a law-yer in Wayland, Massachusetts, to attend a client’s funeral. He discovered Chebeague had a golf course, and that did it for him; he bought an island house and brought the whole family back in 1964 for the summer when Beverly was 15.

Because the family first arrived at the island for the funeral in the fall, after the summer people had left, Beverly right away made friends with the year-round islanders. It was only later that Beverly met summer people, and al-though technically she was someone “from away,” she never considered herself a summer person. One of her first island jobs was teaching swimming to the island children, and she quickly acquired her own island nickname, “Big Bev Ross,” to distinguish her from “Little Bev,” the other Beverly Ross on Chebeague, who was six years younger.

After graduating from high school in Massachusetts, Beverly enrolled in a civil engineering program at Northeastern University in Boston. Northeastern’s curriculum supplements academic coursework with practical internships with the region’s businesses, and Beverly landed a “co-op” position at E. C. Jordan, a Portland-based engineer-ing company, close to Chebeague. In addition to her many friends on Chebeague, where she went for long weekends, Beverly kept a special eye out for Stephen Johnson, a hand-some young fisherman. But Beverly recalls, “He always had a lot of girls around, so I couldn’t get near him.”

She eventually got her chance, and love proved to be a stronger attraction than civil engineering, so in 1970, rather than return to Northeastern, Beverly stayed on Chebeague and married Steve a year later. She worked at E. C. Jordan for a few more years as an engineering tech, and they went lobster fishing together, while supple-menting their income by plumbing with Steve’s father. “We both plumbed and fished,” Beverly recalls, while they worked to earn their master plumber’s licenses. After a while it became clear that someone had to take care of business ashore while the other was out fishing. “Steve loves the water,” said Beverly, “so I kept the plumbing and Steve kept the fishing.”

Beverly eventually trained another female friend, LeeAnn Robinson, as a plumber’s helper to cope with the job’s increasing workload, and they tackled the island’s plumbing challenges, large and small. “Crawling up underneath houses to get at pipes and having your clothes get caught on nails, that was the worst,” says Beverly, who now recalls those challenges perhaps more fondly in retrospect than at the particular moment. When stumped by a particularly oner-ous job that stymied the two of them, all her helper would have to say is “We have to go get Stephen,” Beverly remembers, “and that would get me to finish the job. You can always find a bigger wrench,” she says, especially when the big wrench-turner is out on the water and not immediately available.

As full as her life was, it was still not enough, so Beverly began running marathons. In 1980, she was selected to be part of a team of runners that carried the Olympic torch to the winter games in Lake Placid, New York. Beverly had always had a keen interest in sports growing up, especially long-distance swimming. The great female swimmer, Gertrude Ederle, in particular, was a heroine for Beverly, who swam competitively in Wayland’s Lake Cochituate as a youngster. But she recalls ruefully that she stopped training for swimming events when she no longer wanted to get her hair wet, “because the lifeguards were too cute.”

In 1996, Beverly and Steve decided they wanted kids, but after many unsuccessful procedures they decided to adopt. Beverly had met a woman who had adopted children in Russia, and they immediately began filling out the long application papers and sent them in to the agency. Less than six months later, they brought home a brother and sister named Dennis and Darya, aged five and seven.

As soon as Dennis learned to speak English, he told Beverly and Steve that he and Darya had an older sister, Vika, who had been placed in a different orphanage and who had been left behind in Russia. So a year later, Beverly and Steve went back to Russia and located Viktoria, who was then 12. Because Vika was considered to be of age, she had a choice about whether to stay in Russia or take a big risk and join her brother and sister in America. Vika chose to join her siblings with their new parents. Vika kept up her Russian language skills with a tutor while growing up on Chebeague, and enrolled in Russian language courses in college where she majored in social work. Years after first arriving on Chebeague, Vika returned to Russia as a young woman and worked for a month at Dennis and Darya’s orphanage and eventually located her biological father.

Another tool that fascinated Beverly was the Internet. Ever since her civil engineering days at Northeastern, Beverly had been “into computers,” but when the Internet began to be accessible to people other than academic researchers working for secret government agencies, Beverly, by her own description, “got into it right away.” She quickly taught her-self the coding language HTML (HyperText Markup Language) that is used to program websites, and she launched Chebeague.org in 1996. On this community website, which has essentially remained unchanged for the past decade and a half, Beverly posts news from island organizations, event announcements, births, deaths, weddings, and other news that enables the island’s far-flung friends and “summer natives” to stay in touch with one another all over the country—and around the world. Under Beverly’s tireless ministrations, Chebeague.org has become the heartbeat of the extended island community.

One of her early surprises as the programmer/editor/administrator of Chebeague.org occurred when Marlin Fitzwater, presidents Reagan and George H. W. Bush’s former press secretary, saw a boat listed on the site that was for sale. When Fitzwater arrived on Chebeague and was introduced to her, Beverly remembers he shook her hand and exclaimed, “Beverly Johnson; I know you!” In researching the boat purchase, Beverly recalls, “he had read the whole website and remembered all the details.” Aside from connecting Chebeague’s many friends and relatives all over the world, Beverly mentions that there are also people who have moved to the island due to the website. A family in Georgia was thinking of relocating to Maine and was reading through all the websites of different Maine communities. When they stumbled across Chebeague.org, they saw a story of a school project us-ing chickens to control Asian brown beetles in the school garden. When the family saw that, they said, “That’s it, we’re moving to Chebeague.” The chickens did it for them.

Beverly’s interest in kids and nature led her naturally to her next interest. “I love getting people interested in nature,” she said. When her husband Steve put up a backyard bird-feeder, Beverly was immedi-ately hooked. And then one thing led to another. She began photographing them, using the photographs to assemble an informal life list, and eventually posting the photographs on Chebeague.org. “I don’t count a bird until I have a pic-ture of it, because I have been wrong so many times,” she says. One of the first birds she photographed turned out to be a willow ptarmigan, of which there had only been three sightings in Maine since 1850. The image was up on the website within three hours. Now she is known on the island as the bird paparazzi.

When Stephen gave Beverly a bigger wrench in the form of a telephoto lens, her interest in birds increased exponen-tially. “I always have it with me, because when I don’t there is always a new bird. I let a friend use it to take a picture of a new building, and of course I saw a barred owl in a tree.” Once, she recalls, when a call came in that she had to  take, an osprey came by with a fish. “I should have dropped the phone and gotten the shot, but the person would not have understood that I was birding.”

take, an osprey came by with a fish. “I should have dropped the phone and gotten the shot, but the person would not have understood that I was birding.”

Back on Chebeague’s west end beach, known as The Hook, Beverly reflects back on some of her great birding thrills over the years. She is still excited about the close-up of an eagle, actually taken in her backyard as the national bird eyed a squirrel picking up seeds, and the Wilson’s snipe, a rare sighting that she identified from the image on her camera, and then discovered there was actually a pair of snipes in the frame. She is particularly proud that she has been recently able to acquire a dozen pair of binocu-lars from a local foundation for the island’s schoolchildren, where she serves as a volunteer. “I love it for the kids,” she says. And they clearly love her for it, too.

The westerly wind has picked up on the beach, but the pair of small brown birds with little head crests that may be a new sighting for Beverly are hopping along the strand and pecking at insects at the wrack line. She gets a good identifying shot of them and heads back to her computer, where she quickly recognizes them as a pair of horned larks that nest far to the north in the Arctic, and uploads another unforgettable piece of Chebeague’s story on the Internet. Not a bad day for a woman who says that when she started photographing them a dozen years ago, “I didn’t even know there were birds here.”