When I moved to North Haven, I thought I was moving away from politics. In 1971, I was just out of high school, a veteran of protest marches in a country divided by disputes over the war in Vietnam. That summer, I went to visit a young man on a small island off the coast of Maine. We arrived armed with Helen and Scott Nearing’s The Good Life, that renowned ode to simplicity. We had a two-room cabin right on the beach at the end of a half-mile-long dirt road. There was no running water or electricity. No Walter Cronkite. No marches.

I found myself in a very small community—vastly different from my hometown of Minneapolis—with values and norms that would have been well known to my grandparents, but had skipped a generation and were not yet known to me. And there, my real political education began.

A whole winter passed on the island. To make some money and to pass the time, I made candles from wax melted in a pot on our woodstove. After a discussion or two with teachers in town, I offered to volunteer at the island’s K–12 school. I would share some craft skills, or just be an extra set of hands for the busiest teachers. I’d once worked in a Head Start program, got along well with kids, and knew I would enjoy my time with them.

One morning, I was home alone working on the candles when the school principal drove down our long driveway. I wasn’t accustomed to visitors. He couldn’t stay for coffee. He calmly explained that the school board had met the previous evening and had rejected the notion of my volunteering at the school. Perhaps I was still too much of a newcomer for them to accept. Perhaps I was just . . . not a good fit.

I had grown up in the Midwest. The buildings there were new, and everybody had come from somewhere else. My own grandfather had come to this country as a boy. I had no understanding of the concept of “people from away,” or worse, that if you weren’t born in a town you could be seen as an enemy. That your help, however earnestly offered, might not be welcome.

It was painful. It was humiliating. I’d only wanted to help. But I began to see how I looked to the islanders around me: a woman from another place, living with a man who was not her husband. And that man was a summer kid who should’ve known better than to stick around all winter. And what kind of person lived without water and electricity except by necessity? Who would want a woman like that teaching her kids? Eventually, we left North Haven, and we both went back to school.

Three years passed. I went to College of the Atlantic, and discovered organic farming, a system of agriculture that my ancestors would have recognized as their own. Charlie became a boatbuilder. We got married. We had a baby.

In 1976, we rented a farm on North Haven, and moved back out to the island for good.

It was different the second time. We may have been hippies, but islanders recognized the value of our farm to the community. Though farming had all but disappeared by the late ’70s, North Haven had produced most of its own food—and much more for the markets in Boston—just a century earlier. Our acres of vegetables, our dairy cows, chicken, sheep, and pigs made sense.

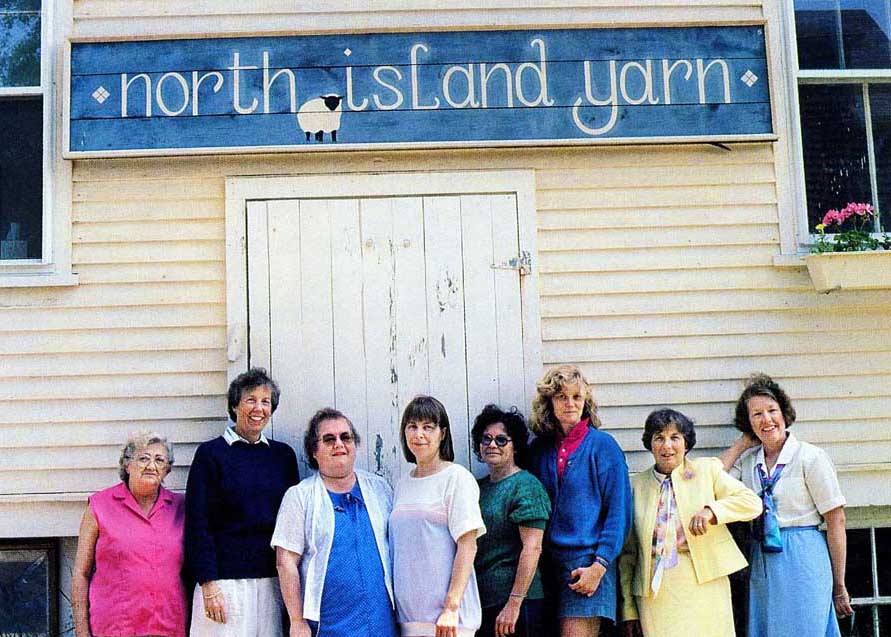

I sought out everyone who had ever raised animals or vegetables to ask them when was the best time to plant my pea seeds, what to do when the sow was ill, or with a cow who wouldn’t stop kicking over the bucket just as I was finishing the long process of milking her. I launched an egg-delivery route. Once or twice a week, I would stop in and sell a dozen eggs to families all over the island. Often they would invite me in to sit a minute, to share a cup of coffee and a few stories. Over time, I got to know my neighbors, their kids, their kitchens and living rooms. They gave me advice about raising my children. I heard about their troubles and learned a tremendous amount from their experience and wisdom.

This, I realize now, was the second phase of my political education. The same people who had eyed me suspiciously three years earlier, who had objected to my mere presence in the public school, now welcomed me for a cup of coffee. They shared advice, secrets, gossip. As we all do, they needed to understand my life, to be able to relate it to their own, before they could trust me.

North Haven, like most small towns in New England, makes most of its critical political decisions at an annual Town Meeting. Everyone plays a part in the process (even those who quietly abstain). It is probably the most transparent and participatory form of government that exists. Because it is an opportunity for people to vote on every elected office and each line item of spending, the discussion can be long and, at times, painful. The elected officials in question are not simply names on a ballot, but brothers, sisters, husbands, neighbors, even oneself. Are the roads in need of new pavement? Should we set aside tax dollars for a new fire truck? Is the school spending too much money on field trips, or basketball games, or salaries? Everything is on the table.

After years of watching, then gradually voicing an opinion, I ran for a spot as tax assessor. (One more piece of political wisdom gleaned: Almost no one wants to be tax assessor. I ran unopposed—and won.) Over the next few years, I became more and more active, emboldened by the support of my neighbors, and fascinated by the challenges of governing. In 1991, twenty years after my arrival on the island, I became the chair of the school board.

Many people in those days talked about the demise of the year-round community on the nearby island of Criehaven. Once their school closed, the young families began to leave. When the young people left, so did their parents and grandparents. Then the store and the minister. No one—no island, no small town—wanted to be the next Criehaven. And everyone agreed that the school, more than any other factor, would determine our fate.

I was chatting with a Republican colleague the other day about what he had done prior to coming to Congress. He recited a long list, including his business activities and serving in the state legislature. Then he said—as I often do—that being the chair of his local school board had been the most difficult political office he had ever held, Congress included. The decisions made by the school board have direct and immediate effects on the property taxes needed from citizens in the town and on the quality of education that kids in town receive, so everyone in town pays attention. Everyone has an opinion. I’ve never been in an office in which every vote was scrutinized so thoroughly, or felt so personally meaningful.

I was elected to the Maine Senate in 1992, where I represented the islands and mainland towns of Knox County for eight years. That first state senate election was a lot like my egg-delivery route: I knocked on more than 5,000 doors, spending untold hours in kitchens and parlors, listening to the opinions, questions, troubles, and hopes of people who appreciated the opportunity to talk to me. And they expected me to get to work!

Just as it was on the island, what was most important to the voters in my senate district was not my ideology, but whether I could be trusted—whether I was one of them. On islands, we don’t have the luxury of relying solely on friends. If you’re stuck in the snow, or there’s trouble on the water, or a child is sick, the first person to come along might be a rival, or an ex, or someone you just don’t like. We have to rely on one another, no matter what. Our isolation makes us more aware of our interdependence.

By any standard political calculation, I was too liberal for many of the Republicans and Independents in my state senate district. I am a Democrat who believes in universal health care and in raising the minimum wage. I support a woman’s right to choose. I can remember more than once meeting a voter who said, “I don’t always agree with you, young lady”—I was younger then—“but I appreciate that you stand up for what you believe in.”

In the Senate, I saw the connection between the issues confronting island towns—such as keeping a school alive and vibrant, and diversifying economies that are increasingly dependent on just a few industries—and rural towns in much of the rest of the state. We began to make meaningful changes by working together.

Islands can be insular places. I believe that a big part of the responsibility of representing an island town is to recognize and seize political opportunities to partner with other constituencies when they arise—to seek strength in numbers.

I received plenty of feedback on our work from fishermen, friends, and neighbors. They’d give me an earful on the ferry, at the grocery store, or over a rum and Coke at the restaurant.

They still do.

I serve in Congress now, a distinct honor, but one that poses real challenges. Unlike the Maine Legislature, not to mention Town Meeting, the political atmosphere in Congress has very little sense of shared sacrifice, of common purpose. It takes hard work to stay connected to the challenges of island communities: maintaining school populations—still a very real challenge for many of our offshore islands and rural towns alike—lobster fishing, economic development, high energy costs.

Whenever I need a little more local thinking, I tag along with a group of old friends who make the trip to Vinalhaven for breakfast together nearly every Sunday morning at 7 a.m. (When I’m feeling energetic, I invite them to my house and cook them up some fresh farm eggs and sausage with home fries.) Most importantly, I pick their brains for whatever they are thinking—about the Maine economy, the future of lobster fishing, or just what they think I ought to be doing down there in Washington. They’re some of the same people who’ve been giving me advice—and criticism—since I first set foot on North Haven. I wonder how often my colleagues are able to do the same.

In the midst of the debate over the Affordable Care Act, I often thought of Town Meeting on North Haven. Here on our island, 12 miles offshore, we need to have reliable medical care. Sure, there’s a hospital on the mainland, but what if the weather’s too rough for the ferry to go? What about an illness in the middle of the night? What if the baby comes too soon? Neither our seniors nor the young families we work so hard to attract—and retain—want to live in a town without basic primary care.

But we simply don’t have enough patients in our town to make a physician’s practice profitable. So years ago, this town—traditionally Republican, full of Yankees who exhibit a tendency toward penny-pinching that would have made my accountant father proud—decided to make practicing medicine on the island worthwhile. Every year, at Town Meeting, we vote to subsidize a doctor or other health-care provider, paying their salary, maintaining a house, supporting the clinic and its staff. This is what socialized medicine really looks like: a whole town choosing to secure a vital service for themselves, and choosing to bear the cost equitably.

To be sure, we still argue over the expenses year after year. Just as we do with the school, we have to constantly assess our expectations and our ability to pay for the services we choose. But the decision isn’t made along party lines; it’s made according to the needs of the community. And so are the decisions about the school—which is still going strong, the smallest K–12 public school in Maine—and paving the roads, and plowing the snow, and maintaining our park.

I’ve learned more representing island towns than I could possibly have imagined. But the most important lesson—the one that comes back to me at every Town Meeting, the one that makes me think of my own tentative journey into this community all these years ago—is this: We’re all in this together. A sustainable community provides everyone with a chance to succeed, whether by getting a basic education or being able to start their own business or feeling confident that they can stay healthy. That community cannot remain without cooperation.

We come from different backgrounds and different beliefs about the world, and it’s only natural that we will disagree on how to handle the challenges before us. But that does not excuse us from our responsibility to get together and solve our problems. I think islanders understand that a little better than most. They certainly understand it better than many members of Congress, who are content to live with political gridlock because it doesn’t touch their lives in a meaningful way. People from small Maine towns making hard budget decisions—particularly those on offshore islands—don’t have that luxury.

When I return to D.C. to debate and vote, I try to remember the feeling of Town Meeting: people listening respectfully despite tremendous differences, the swell of pride and anxiety that comes with being chosen by neighbors to make critical decisions, the sense that compromise is a virtue. That’s what I take with me.

Chellie Pingree is a member and former trustee of the Island Institute. She represents the 1st District of Maine in the US House of Representatives.