Back in the early 1960s, we’d pile into the wood-panel station wagon and drive from our house within mystic earshot of the Two Lights foghorn to Massachusetts to visit my father’s family. The North Shore seemed interminably far away. We kids preferred the shorter drives to our mother’s sisters’ homes around Portland and the Midcoast, where her family had first arrived 200 years before.

On one of those drives, maybe it was 1962, we were headed south on the Turnpike, around Kennebunk. Clots of cars and trucks were churning northward in the other lane. Look at all the traffic, my mother said with a kind of slow-motion amazement, all from away.

In that vivid mnemonic snapshot, the traffic is nothing like the practically unbroken streams of weaving vehicles we see even on an off-season weekday now.

Time has a way of sanding down the rough parts of the past. The phrase “from away,” for example, is largely just a punchline nowadays. A caricature, which could come straight out of Marshall Dodge’s Bert & I stories or Jim Brunelle’s Over to Home & from Away collection of the 1980s.

Laconic Mainers. Ironic Mainers. Canny Mainers tweaking numbskull summer people. Parochial Mainers resisting the outside world. In my childhood, “from away” was indeed a trope for dry humor. But it had other connotations, too. I think you have to have lived here all your life, since before about 1965, to understand that it once was metonymic code for deep cultural scarring.

That north-moving highway traffic was regarded, at least subconsciously, with suspicion, plus an array of other feelings that included pride, inferiority, uncertainty, distrust, a certain irritability, anger, resignation, and the twinkling irony that pervaded much of Maine’s experience of summer people. As far as I know there are no sociological studies analyzing this. But if the Portland novelist Agnes Bushell was right when she said that “literature transmits our cultural memory,” then there’s a reliable record of the feelings that underlie my mother’s phrase “from away.”

Tourism began in Maine long before the 20th century. The first reputed “tourist destination” was a farmhouse near Saco converted in 1837 for summer guests. By the 1880s the neighborhood had turned into Old Orchard Beach, and trains were running to resort hotels on Moosehead Lake. By the turn of the century “rusticators” were driving cars up what would be called the Atlantic Highway. In 1905 a state highway commission was established. In 1922, the first Route 1 signs went up and the Maine Publicity Bureau was established.

By the 1930s, summer visitors like the Connecticut banker and influential poet Wallace Stevens were vacationing in Pemaquid and points Downeast, making up one kind of well-off summer people. Another kind were the bona fide wealthy, who in the 1800s started buying pieces of the coast, building “cottages” that to the fishing communities were mansions and closing off the grounds.

One spillover effect of this has been long-running wars over shorefront rights and uses: By some estimates, about 88 percent of Maine’s roughly 4,500 miles of coast is privately owned. When wealth moves in, property values go up, taxes soar, and the locals have to move. A certain resentment sets in and accumulates.

From early on, these summer people needed services. The locals took the role because their economic means were by and large scant, one big difference between them and the people from away. They thought of themselves differently.

Historically, at least some of Maine’s population had fled into harsher winters to get away, as it were, from the oppressions of Massachusetts society. Their pride was, in general, high. Their social standing was low. Most of them did not have the education, family, friends, or business connections the summer people had. They spoke differently. They had livelihoods, not occupations: a banker is one thing, a fishing-farming household is another. And fishing-farming-servicing, yet another.

Services, servants, servitude. When pride encounters servitude, humiliation ensues. It “distorts the soul and damages the personality,” to invoke Martin Luther King Jr.’s words. Now, we are not talking about slavery, here—though later we’ll see how race considerations enter the picture. But we are talking about people from away treating locals as servants.

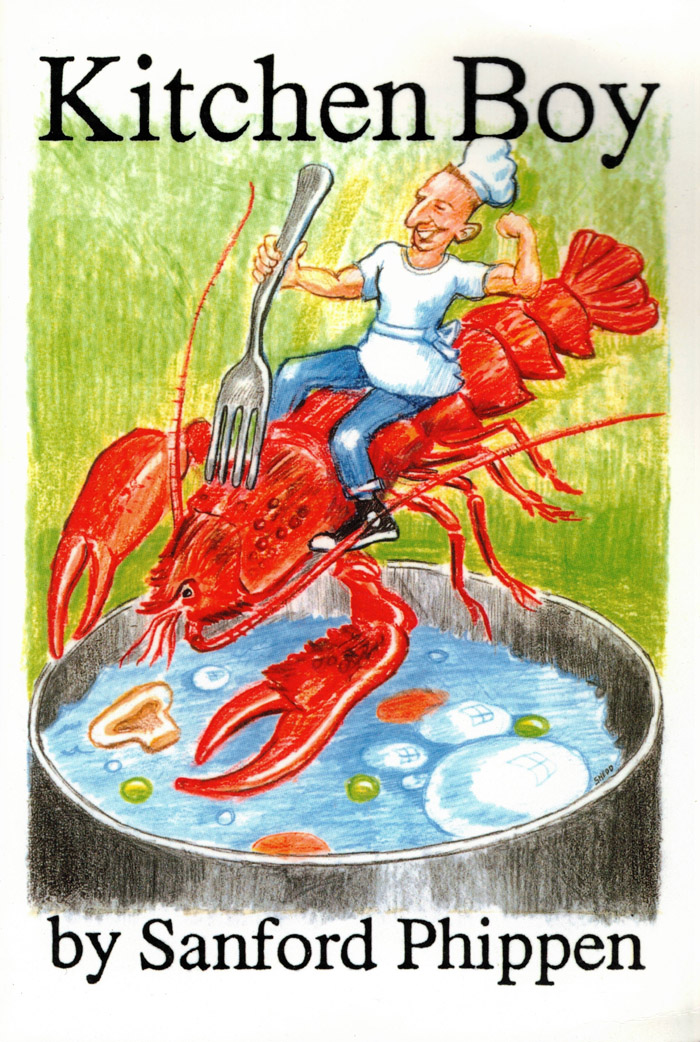

A wry and breezily good-humored account of distinctions between the locals and the well-to-do appears in Sanford Phippen’s novel Kitchen Boy (1996), based on his own experience as a hotel worker in 1960 Hancock County.

Phippen’s main character, Andy, the hotel’s all-purpose kitchen boy, has ambitions and plans to attend the University of Maine. He has a good-natured, if wily understanding of how to charm the guests from away who might help him. His young neighbor, Mary Treat, is less clever about it. Her father is a TV repairman, though this does not stop her from promoting the fiction that her family used to be well-to-do.

Lacking Andy’s finesse, she is openly on the lookout for aristocrats who might help her climb (back) up the social scale. To emphasize the point, she defiantly tells Andy, “‘I’M DEFINITELY NOT GOING TO COLLEGE IN MAINE!’” while sitting “in the servants’ dining room across the table from me while I was trying to answer a letter.”

Phippen’s prose is so breezy you can miss in this sentence the word “servants,” pregnant with the book’s core irony. Mary thinks of herself with a sense of social inferiority that she pridefully wants to turn into superiority by elevating herself at the expense of lowering her compeers. This scars the situation even for wry-natured Andy. Mary’s “name-dropping and acting superior to us local yokels did get tiresome,” he remarks.

Mary is going to get out of local-yokel Maine, and she’s angry about it. This is a kind of community self-denigration that eats some working-class souls alive.

“The servantry then. The way you were lined up on the carpet, disciplined to hear over and over the laws of keeping place. Rule one: Never speak.”

So opens Patricia Smith Ranzoni’s poem “Cultural Guide, or Why Doesn’t the Humanities Council Fund a Documentary Before Those Who Know Are Gone” (first published in her collection Settling (2000)). Ranzoni grew up in 1940s Bucksport, not far from Phippen’s Hancock, in the lower reaches of rural Maine poverty. She, too, served the well-to-do from away when young, and her determination to go to college led her into childhood development teaching and counseling. Along the way she grew only prouder of Maine’s past, and angrier.

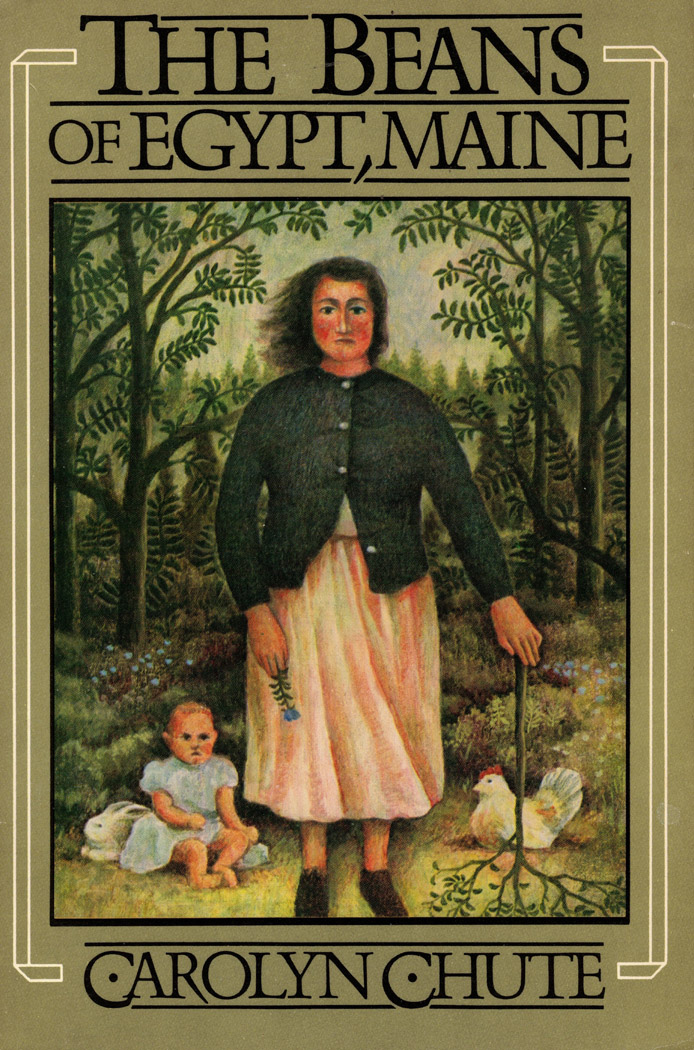

No one in Maine—with the possible exception of Carolyn Chute in her 1984 novel The Beans of Egypt, Maine—has spoken about rural Maine poverty more evocatively and authentically than Ranzoni. Her themes run a range from the heartwarming hearth to bitterness bred in the darker realities of the hotel-worker’s soul that Phippen skates over.

“Cultural Guide” details the ways in which the locals are made to feel “there / but not there.” The sense of being invisible carries straight out of the hotel into the way you think of yourself. You can lose the dignity of your own presence. Humiliation, anger, resentment result. And their object, for better or worse, becomes the people from away whose presence erases yours.

There are many ways to misunderstand the scars of class divisions, including sympathetic. At Colby College’s Women in the Arts gathering in 2001, Ranzoni gave a reading titled “Making Water, Making Up Our Minds, Am I Your Sister? Poems and Stories of Comfort and Discomfort from Outback Maine.” Her trenchant poem “To Colby Trembling (Am I Your Sister?)” recounts her first visit to Colby’s campus as a teenager in a debate contest and how utterly out of place she felt—one of “the Tallulah Turnipheads who come with everything they own in a cardboard box” as even her own future school, the University of Maine, characterized her.

Fifty years later, she asked the well-off academics, from both home and away, if they really understand “how it feels to cross to where the privileged are along the coast and want to warn / that Stonington girl in the yacht club parking lot with that fellow in his boating clothes can’t / she see she doesn’t fit why aren’t they on the veranda and what ache she is begging for her heart?

The psychic pain, in other words, that the underclasses suffer, and that the academics have a long tradition of not understanding. Charles W. Eliot’s 1899 book John Gilley: Maine Farmer and Fisherman reads like a fairy tale of the fishing-farming life on Mount Desert Island; nice try, but his colleagues in Massachusetts excoriated him for wasting his time on these people. Ranzoni read her poem near the end of the conference to a near-empty room, she told me.

Class divisions have a way of not going away.

In the 1970s and ’80s, Maine became not just a summer destination fashionable among the affluent, but a cool place to live. Lew Dietz in Night Train at Wiscasset Station (1977) described the influx of settlers from away as “a mixed bag of retirees, young homesteaders, romantics, and escapees from postindustrial America … who proceed to direct their energies to changing Maine in the name of progress.”

The back-to-the-land offshoot of the hippie movement brought thousands of young people from away to the woods of Knox, Waldo, Oxford, Somerset, and other counties that seemed out of the way to mid-Atlantic suburban sensibilities. Maybe the phrase “off the grid” arose here, who knows. Portland’s burgeoning cultural and real estate scenes attracted avaricious yuppies in droves.

“The condos arrived, the poets left,” wrote Bushell in 1995. Many found winter inconvenient and bounced out, but many did not. They had kids, assimilated over the decades, and changed Maine’s social and cultural landscapes, and voices, forever.

The aftermath of those changes is clearly depicted in Elizabeth Strout’s book of short stories Olive, Again (2019). Strout grew up in Portland, half a generation or so after Ranzoni and Phippen. Her character Olive Kitteredge lives in Crosby, a fictional town located in the vicinity of Brunswick.

Practically every story in Olive, Again shines light on frictions between people from middle class coastal Maine (who had been deftly depicted around midcentury by Ruth Moore) and people from away. Everyone in the book who grew up in Crosby—or in nearby Shirley Falls—lives in a kind of social no-man’s-land whose trenches are exposed when people from away show up.

Olive’s response is a kind of implicit defiance: She is dead set, no matter who you think you are, that she is who she is, take it or leave it. She has what Dietz called Mainers’ “prickly pride,” or what Leo Connellan in his poem “Lobster Claw” called, with more rawness, “our / self-contained resentment.”

While Olive is nearer Phippen and Ranzoni’s age, Crosby and Shirley Falls’s later generations came of age during and after the changes of the 1970s and ’80s. Unlike Olive, they are not laconic, ironic Maine Yankees, but people who benefited socially and economically from the influx from away.

Olive’s son, Christopher, is a podiatrist in New York City. Jim and Bob Burgess became big-time lawyers in New York; their sister, Susan, became an optometrist and settled back in Shirley Falls. The Burgesses are haunted by memories of growing up poor. The actual poor of Ranzoni, Chute’s Beans, even Mary Treat, not the romanticized poor of Charles Eliot or Ranzoni’s middle-class academics.

Jim’s wife Helen, who is a well-to-do New Yorker, and the Crosby residents are like repelling magnets to each other, even the Burgesses. “’She’s just so rich,’” Bob’s wife, the UU pastor, observes. Helen can’t wait to get back to New York City, and the locals can’t wait for her to leave.

Olive’s second husband, Jack, is a former Harvard professor who retired to Maine. Each is well-aware of the social distance between them: “I’m a peasant and Jack is not,” Olive says at one point. “It’s a class thing.” Bluntly crystallizing centuries of Maine’s social reality.

In the 1980s whole literary conferences were held to debate who qualifies as a “Maine writer,” which was code for generational Mainers—some, anyway—trying to hang onto a certain identity, a certain class heritage, that was dissolving. By now, 30-plus years later, the dust has pretty much settled on those frictions. Maine is full of people who were born and raised here who have no laconic, ironic, ancestral prickliness at all, and “from away” is a punch line from a bygone era. All the people who live and write in Maine are Maine writers.

All the white people, that is. A recurrent friction in Olive, Again involves Somalis who have set up an expanding community in Shirley Falls. There’s a lot of ambivalence about them in Crosby. Olive’s first home health nurse, Betty, has on her truck “a bumper sticker for that horrible orange-haired man who was president,” as Olive disgustedly observes.

Soon a different nurse’s aide, Halima, replaces Betty. Olive guesses correctly that Halima lives in Shirley Falls and that her family spent time in Kenyan refugee camps. Later when they talk about Betty, Olive says to Halima, “She’s an idiot.” “You mean her bumper sticker?” Halima says, and Olive, with classic Maine prickliness, replies, “Yes … that is exactly what I mean.”

In the 21st century, it’s the Somalis who are from away. Far, far away, as it happens, not wealthy but not white, marking them as the target for generational social resentments that include a heavy dose of racism. The feelings of inferiority, suspicion, anger, pride, and irony are re-placed onto the immigrants. Betty is an avatar of Mary Treat, finding a different fiction to elevate her social dignity. She’s more than a local yokel, and angry about it. Class divisions have a way of not going away.

I don’t know. Maybe you had to grow up here in the middle of the 20th century, and take some scarring, to understand “how it feels to cross to where the privileged are.” How it felt to wonder what was behind that big gate closing off the grounds of Bette Davis’s house on the shore in Cape Elizabeth. To wonder how Edna St. Vincent Millay got to that lone cottage on Ragged Island from rough and tumble Rockland—the place Leo Connellan wrote of with persistent bitterness.

“Lime City has become hamburger stands now / and unskilled crime committed / from despair’s overwhelming fatigue,” he says in The Clear Blue Lobster-Water Country. Maine is spectacularly beautiful in summer, and brutal in winter for those who cannot afford to get away.

Soon after the COVID-19 pandemic struck, a version of generational suspicion—I suspect—prompted some locals to try to quarantine three out-of-staters in a house on Vinalhaven. In 2021, people from away were paying cash for homes in Knox County whose median prices had jumped from $236,125 in 2019 to $285,000. Is wealth moving in, again?

In the next 50 years hotter, drier, and increasingly calamitous weather conditions will almost certainly drive more people up the Turnpike north to Vacationland.

Dana Wilde is a nature columnist, book reviewer, former news editor and college professor. His recent books are A Backyard Book of Spiders in Maine and Winter: Notes and Numina from the Maine Woods. He lives in Troy.