Joseph William Lunt wakes up before the sun in a house that sits on a harbor that shares his name. Aboard his lobster boat Heritage, Lunt does what his ancestors have been doing for over two centuries—he harvests the bounty of Downeast Maine waters.

His wife Teenie Lunt also fishes out of Lunt Harbor in her own lobster boat, named Hezekia David after their two-year-old son. Joe, Teenie, and Hezekiah are three of about 40 year-round residents of Frenchboro, the smallest town in Maine. Technically, the town of Frenchboro comprises several nearby islands, including Great Duck, Black, Pond, and Placentia—all of which were once home to year-round communities. The only permanent settlement remaining can be found around Lunt Harbor on the northwest corner of what is also known as Outer Long Island, seven miles off Bass Harbor.

“It’s an instinct,” Joe, a ninth-generation islander, says of fishing. “When I was a kid, my family set me up with a skiff to use and some starter traps. Fishing to me has always been all-encompassing.”

Life on Frenchboro is inextricably tied to natural resources. Before lobstering, islanders fished for cod, harvested lumber, and even gathered large beach stones that were once used to pave city roads, allowing the community to thrive since 1822 when two brothers started the first permanent settlement on the island.

The Lunt Family lived on Mount Desert Island, but owned land on Outer Long Island and fished the surrounding waters. Seeing an opportunity in the small island’s natural resources, two Lunt brothers, Israel B. Lunt and Amos C. Lunt, decided to build a life there. They married two daughters of another island landowner, and soon their father and uncle moved out as well.

The four men fathered 54 children, most of whom lived on the island. What began as subsistence fishing evolved into a major seafood business for the men. The Lunts have been the prevailing family there ever since, serving as community leaders shaping the island’s trajectory.

By the late 20th century, little had changed. Born in 1987, Joe Lunt recalls that during his childhood, most residents of Frenchboro could trace their ancestry back to the island’s first Lunts. Most were, in some way or another, his family. Through marriage, Lunts became Davises, Thompsons, Pomroys, and Teels, among other common island names. The close-knit community can appear idyllic, but sometimes the proximity to one’s family and neighbors can amplify disagreements and cause tension.

In his book Hauling by Hand, an expansive history on the Lunt heritage, writer and storyteller Dean Lunt (Joe’s uncle) writes of both the highs and the lows of the Lunt legacy:

“The family flourished and failed and feuded on the shores of Long Island. They were keen business operators, tireless workers, layabouts, bandits, alcoholics, church workers, community leaders, detached, mean, congenial and fun-loving along the banks of a harbor that bears the family name and on hillsides that contain the bodies of their forebears.”

Despite being connected to the island community by blood, many Lunts have left, never to return, with changing times, family disagreements, and the allure of mainland convenience as causes. The population peaked in 1910 at around 200 residents, and the decline has been a serious challenge in recent decades. Joe refers to his grandfather’s generation as the “Lost Generation” of Frenchboro, because during their time it became increasingly attractive to make a living and raise families on the mainland. More chose to leave than to stay.

Others have embraced the community and fishing heritage, especially in Joe’s direct lineage. Joe’s father David W. Lunt has been fishing out of Lunt Harbor since he was a child and is a dedicated fisherman and talented boat captain. His father before him, David L. Lunt, embodied that same work ethic and founded Lunt and Lunt Lobster Company alongside his father, Sanford (Dick) Lunt.

Aside from fishing, the Lunts have a penchant for filling community leadership positions.

Nearly all the previously mentioned Lunts have served on the community’s select board and other town boards and committees. David L. Lunt served on the Island Institute board of trustees and provided an influential island perspective for the organization between 1996 and 2002.

It is not only the Lunt patriarchs that have allowed Frenchboro to flourish. The women of the Lunt family have also left their mark. Author Dean Lunt reflects on the influence of his grandmother Vivian with admiration. He views her as a role model and attributes much of his proclivity for storytelling and historical documentation to her.

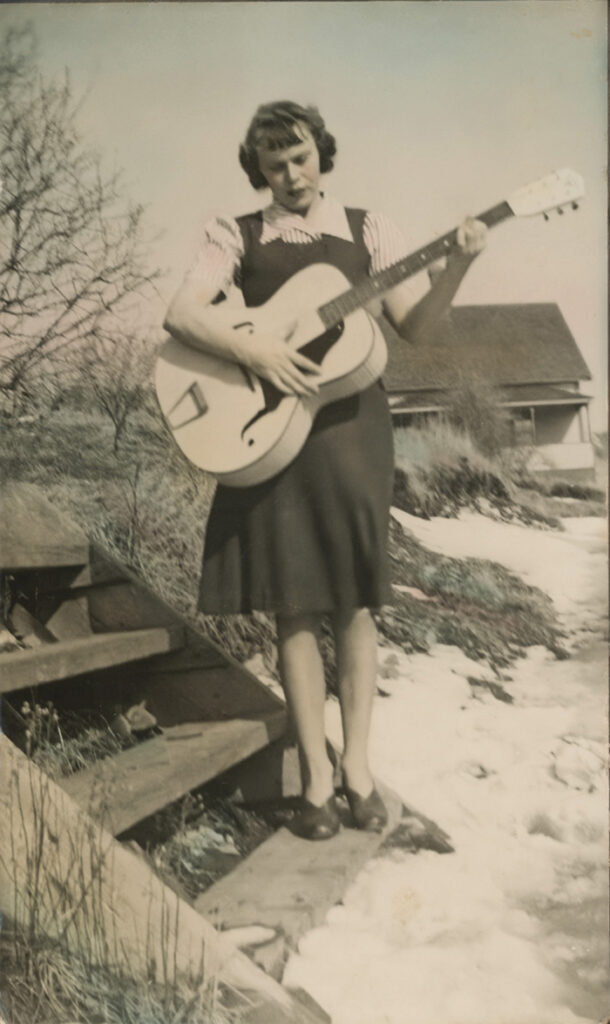

Vivian Davis Lunt was born in 1915 in a small fish house on Lunt Harbor, and in her own words, she was raised “as poor as a church mouse.” As the oldest daughter, she was responsible for tending to her ailing mother, who died of cancer at a young age. Vivian dropped out of high school, but despite her unfinished education she spent much of her adult life learning new skills. She was a self-taught painter, studied fashion design, and eventually earned her GED. She was profoundly studious and learned how to invest in the stock market. While her husband fished and worked the docks, she was the financial mastermind behind the island lobster company they ran together.

As the unofficial Frenchboro historian of the 20th century, Vivian also studied the island’s genealogy. Through oral history and written records she unearthed, she catalogued the island’s family trees. She and her sister Lillian founded the Frenchboro Historical Society together, and by the 1980s, Vivian’s influence was integrated into nearly every facet of island life. She was president of the historical society, treasurer of the Frenchboro Church, and a member of the planning board and school board.

“I loved her to death,” Dean recalls. “She was a big supporter of mine, and she always emphasized the importance of me getting an education.”

Vivian attended Dean’s college graduation at Syracuse University, and was delighted by the fact that Malcolm Forbes was the commencement speaker at her grandson’s graduation. She died in 2009 at the age of 93.

In 1979, Dean was the only school child on the island. The role of school-aged children is critical to Frenchboro, as it is for other islands. Islanders have been creative in attracting newcomers to keep the island school open. One initiative was the Homestead Project which aimed to attract new island families and diversify Frenchboro’s livelihoods by constructing modest two-story homes that were affordable for middle-income families. National media picked up the story, and applicants flooded in from around the country. The catch was that before applicants were selected, they had to visit in person and be approved by the community as a good match.

As the newcomers began to integrate, conflicts inevitably arose. In an August 1995 story headlined “Island Dreams Fade in Maine,” The Boston Globe reported on the disagreements between longtime islanders and those who arrived through the program. One couple, Joe and Sue Sylvester, decided to return to Massachusetts, with Sue telling the newspaper that “The Lunts are a great family… but they are so used to their way, and their way is the only way.”

Joe added: “You take a small, insular community of 45 to 50 people, and you take people from outside and drop them in, you’d be crazy not to think there would be some tension.”

Although the Homestead Project did not unfold as intended, it did introduce new homes to an island community that chronically struggles with affordable housing. If it weren’t for the initiative, Cody and Mable Lunt would have had a harder time finding a home on island to raise a family.

Cody Lunt is a fisherman, holds the town’s snowplow contract, and sits on the select board alongside his father’s cousin, Joe Lunt. Mable serves as the education technician at the school, town emergency coordinator, member of the municipal advisory council, and chair of the Frenchboro Church board. They have three children, ages three, five, and seven.

Joe Lunt feels the weight that comes with island leadership. He recalls being repeatedly asked to join the select board throughout his 20s, eventually agreeing where he has since been at the forefront of major community decisions on issues ranging from land use to community infrastructure threatened by the increasing storm surges.

He sees himself serving as a bridge between where his family has been and where it will be in the coming years.

“I always liked to sit down with the older generations and learn about the way things used to be on the island. My great uncle Big John used to tell me stories about when he was young. I gained a lot of knowledge from that. It set me up as I grew older and moved into more positions of leadership.”

Joe and Teenie’s son Hezekiah David was born in 2022, the 200th year of the Lunt settlement on Outer Long Island. Joe wants to keep the island community alive; that effort means slowing or reversing the tide on the waning population. He also faces the weight of doing what’s right not only for his community, but for his family.

Two other unknowns concern him: Will the next generation want to fish? And will they be able to make a living doing it?

“If you don’t have concerns about the future of this industry, all you have to do is look around,” he says. “It comes at you from every direction—maintaining the right to fish here, how expensive everything has gotten, the politics. A wharf in the harbor got completely swept away by the January storm. It’s more uncertain now than ever, and there is no year-round population here if we’re unable to fish.”

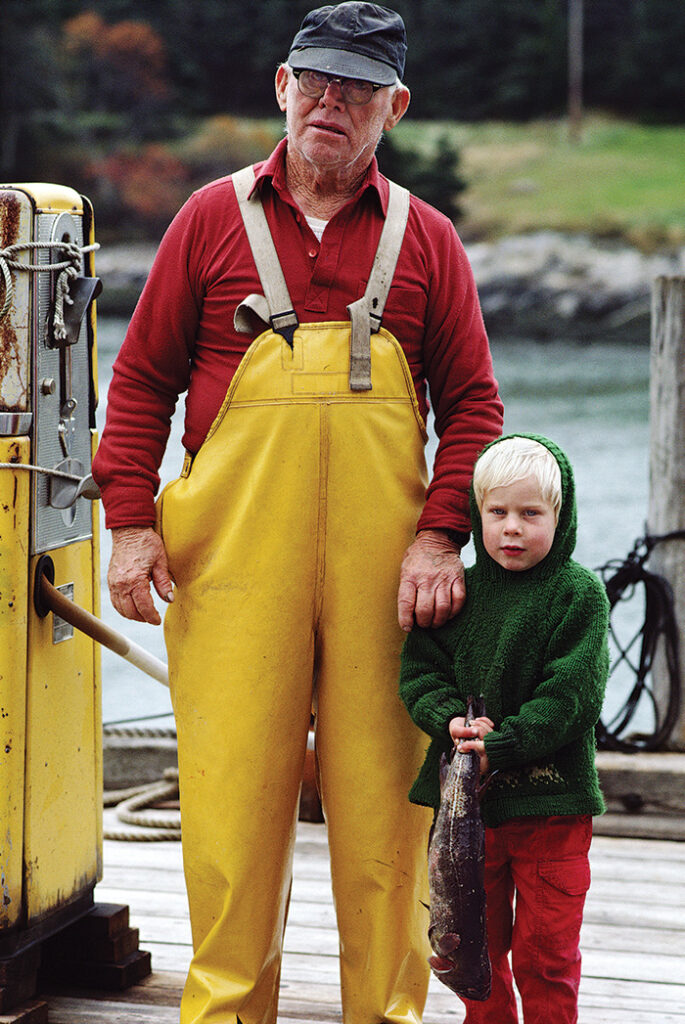

At age two, Hezekiah is immersed in fishing culture and has spent many days aboard Heritage with his parents. Even the name Hezekiah is a callback to Lunt heritage. In the 1850 U.S. census the name Hezekiah Lunt appears for the first time in written island history. It would continue to be a family name, just like Joseph and David.

A little more than a mile east of Lunt Harbor is a landmass that juts out of Outer Long Island, known as Rich’s Head, named for the family that built the island’s other year-round settlement. It is now completely overgrown by forest, save for a few barely distinguishable cellar holes.

Frenchboro and the other 14 year-round island communities that remain surely did not outlast the others by luck alone. Their survival is to the credit of those who know how balance legacy with the willingness to innovate, adapt, and forge ahead.

Jack Sullivan is a multimedia storyteller for Island Institute.